Tuesday in the Fifth Week of Lent: Numbers 21:4-9, John 8:21-30.

Today’s readings present us with a seminal scene from the Old Testament that bridges the entire span of salvation history from the Garden of Eden to Christ’s Paschal Sacrifice on the Cross. In the gospel, Jesus speaks of himself in terms of the actions of Moses in the Old Testament reading, and in this way, the two passages — 1,475 years apart — shed light on one another.

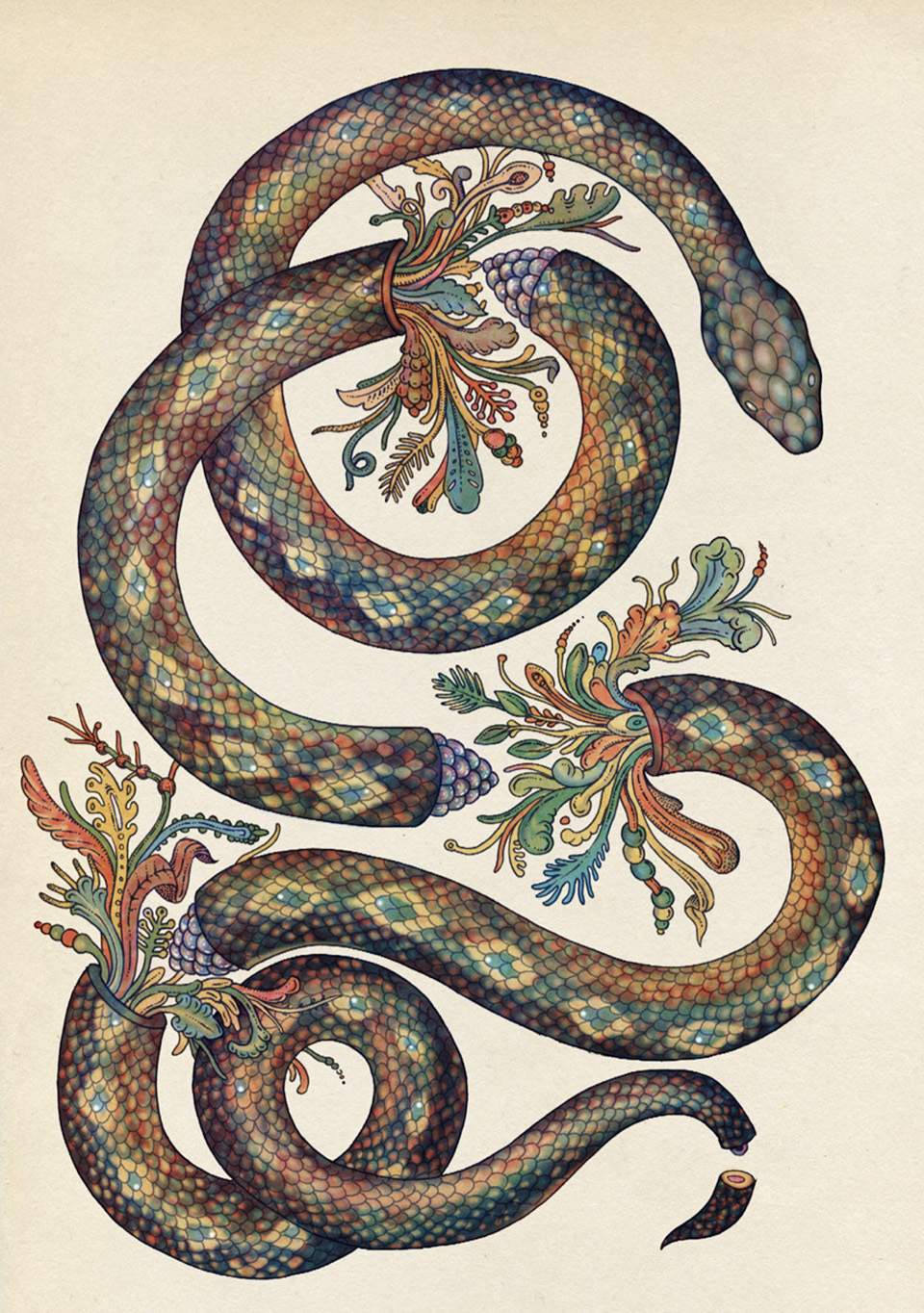

The passage from the Book of Numbers is exceedingly odd at first glance: the Lord punishes the Israelites for complaining by sending poisonous serpents among them; upon their admission of guilt and atonement, Moses prays for deliverance, after which God instructs him to mount a serpent on a pole; subsequently, when the people look up at the serpent on the pole after being bitten, they are spared from death. What kind of witchcraft is going on here? A magic serpent staff to ward off a plague of poisonous snakes?

Let’s slowly interrogate this story to understand what’s going on. First, what is this great sin that deserves a plague of poisonous snakes? On one hand, it seems like somewhat innocuous, albeit irritating, grumbling. We hear, “But with their patience worn out by the journey, the people complained against God and Moses.” This is just human nature, right? However, it wasn’t general complaining, it was complaining specifically against God and Moses. It showed a lack of trust, despite the wonders given to them in escaping Egypt, encountering God on Mt. Sinai, receiving the commandments, being given manna and quail and water from a rock. Mistrust in the midst of wonders — does this remind us of anyone? How about Adam and Eve? And who plants the seeds of mistrusting God in the mind of Eve but the serpent? Thus, God’s sending of the serpents is the reminder of humanity’s original sin in mistrusting God’s providence and grace.

It would be fair to say that the serpent is the symbol of humanity’s sin against God. This sin is poisonous and it brings about the reign of death. The people repent and say to Moses, “We have sinned in complaining against the LORD and you. Pray the LORD to take the serpents away from us.” The first requirement in the recipe for God’s mercy has been met: contrition. Next comes Moses’s prayer, followed by divine mercy in the form of … well, another serpent. God instructs Moses to “mount it on a pole, and whoever looks at it after being bitten will live.” The Word of God truly seems baffling here, clearly operating on a level that is not immediately evident. Nonetheless, being the obedient servant of God that he is, Moses complies with the Lord’s instructions, “and whenever anyone who had been bitten by a serpent looked at the bronze serpent, he lived.” The act of looking up, heavenward, to the sign of the sin they lived with, is the action that reminds them of their dependence on God and his saving mercy. God’s divine mercy flows to the sinful, bitten individual in that moment, not through the arcane power of a bronze staff, but through the symbol that the staff presents to the Jewish believers in God. As Catholics, we know well that in the liturgy, divine sanctification works in and through symbols, from the altar and ambo to the bread and wine. The bronze serpent on the staff is this type of sacramentalized symbol that His prophet on earth made under His instruction.

The Jews understood the symbolic and importance of this staff as a way to encounter God’s grace and kept it around for centuries. They may have begun to confuse the symbolic function of the staff with a divine presence, however, because 740-ish years later we read in 2 Kings that King Hezekiah orders the destruction of the staff, which he calls Nehushtan (“a mere piece of brass”) because the Jews were burning incense to it and essentially treating it like an idol.

Now I don’t know much about divine numerology, but I do find it interesting that exactly another 740-ish years later, we hear Jesus tell Nicodemus the Pharisee: “just as Moses lifted up the serpent in the wilderness, so must the Son of Man be lifted up, that whoever believes in him may have eternal life” (Jn 3:14-15). With this statement, the Word of God doesn’t just restore the symbolic importance of the serpent staff, he also reveals the full scope of this symbol Moses was instructed to make. “Just as Moses lifted up the serpent” — note that the parallel being drawn is to the fixing of the serpent to the pole and lifting it up, not to the serpent itself (in other words, Jesus is not comparing himself to a serpent!). “So must the Son of Man be lifted up” — this refers to his crucifixion, where he becomes the ultimate symbol for humanity; and note that he refers to his human nature here when saying “Son of Man” to emphasize that the same sin symbolized by the serpent is being affixed to the cross in the sins of the human person, for which Jesus stands in as a sacrificial lamb. And finally the salvific import: “that whoever believes in him may have eternal life.” Just as the Jews who were sinful and bitten by snakes saw the staff were reminded of their belief in God and were saved from dying at that moment, we have an infinitely greater promise and divine grace given to us when we behold Christ on the Cross, believe in Him, and are granted eternal life that eradicates all sway of death, as if it is only sleep by another name (as we explored in the reflection, See the Glory of God).

Sometimes the scope of God’s saving plan is just breathtaking. So many moments of patience and mercy over the millennia, from Adam and Eve, through Moses, and ultimately Jesus Christ. And so subversive of our normal worldly affections, too, in the use of the lowly and hated serpent as a resounding symbol for overcoming sin, much like using the reviled Cross as a throne for our Savior.

All of this brings us to today’s gospel, where Jesus tells the Pharisees “if you do not believe that I AM, you will die in your sins.” This is one of a series of super bold statements John reports of Jesus. It doesn’t get much more blunt than this; by invoking the name of YAHWEH in reference to Himself (I AM Who I AM), Jesus is clearly saying that he is God as well as a man. Plus, He tells them that only a belief in Him as God will save them from dying in sin. We can hear echoes of his conversation with Nicodemus, “whoever believes in him may have eternal life.” His message is consistent and resounding: He is to be the symbol of sin pinned down, raised up on a Cross in hatred by men, but in reality a sacrament of God’s grace and love. This is the Word of God writ large in the temple; this is stunning.

The Pharisees don’t get it. All they can say is, “Who are you?” The scribes and Pharisees in John’s gospel seem to be stuck in this morass of defining Jesus’s provenance. Later in this chapter, they will say, “Aren’t we right in saying that you are a Samaritan and demon-possessed?” And we’ve already heard them get hung up on their belief that the Messiah could never come from Galilee. Over and over, Jesus tries to tell them that he is from the one “who is true,” that His Father is in heaven. But this truth is too radical, too supernatural, too blasphemous in their minds to even compute.

Jesus tries again in today’s reading to make Himself clear:

When you lift up the Son of Man,

then you will realize that I AM,

and that I do nothing on my own,

but I say only what the Father taught me.

The one who sent me is with me.

He has not left me alone,

because I always do what is pleasing to him.

Again, it is simply stunning to me how he refers to Himself as “I AM” and constantly puts the focus back on God the Father. It is plain as day. Whoever tries to tell you that Jesus was a social rabble-rouser and malcontent, like so many other “Messiahs” at this point in history, well that person needs to read the Bible a little more closely. What political activist uses his moment in the limelight to say “I do nothing on my own but I only say what the Father taught me”? He does not seek glory and He has hard teachings (such as eating His Body and drinking His Blood for salvation) that push away many would-be followers. And He literally schools the experts in Jewish law (see yesterday’s post), establishing His own wisdom and command over divine teaching. Finally, we have His selfless, miraculous death and resurrection, when the Son of Man is raised like the serpent staff of Moses for us to gaze upon.

Our only job at this point is to believe. To fully believe after we have been given such wonders. Let us not be like Adam and Eve and mistrust God in the midst of the wonders we are given. Let us not be like the Israelites in the Exodus who do the same. We are a new people, the Church, in a New Covenant, and have been given the greatest sacrament of all.

Pingback: Community in the Spirit - Apostolic Church