Fifth Sunday of Lent: Ezekiel 37:12-14, Romans 8:8-11, John 11:1-45.

Resurrection. Each one of today’s readings discusses resurrection. The gospel presents us with the last of Jesus’s great signs in St. John’s gospel, the raising of Lazarus from the dead. We must ask ourselves: what do the prophets and Jesus have to say about death and overcoming death?

Through the mouths of prophets in the Old Testament, God promises us a triumph over death. Because He speaks to us through analogy, millennia of commentators juggle the importance of the literal resurrection of the body, the salvific resurrection at the final judgment, and a more fundamental aspect of the triumph of the Spirit. What we hear in today’s reading seems to be not just a spiritual triumph, but a bodily triumph. We hear from Ezekiel: “O my people, I will open your graves and have you rise from them.” He also says, “I will put my spirit in you that you may live, and I will settle you upon your land,” so the body and spirit are essential in this triumph over death. We clearly hear that bodies will rise from graves, and the Spirit of the Lord will be put into them.

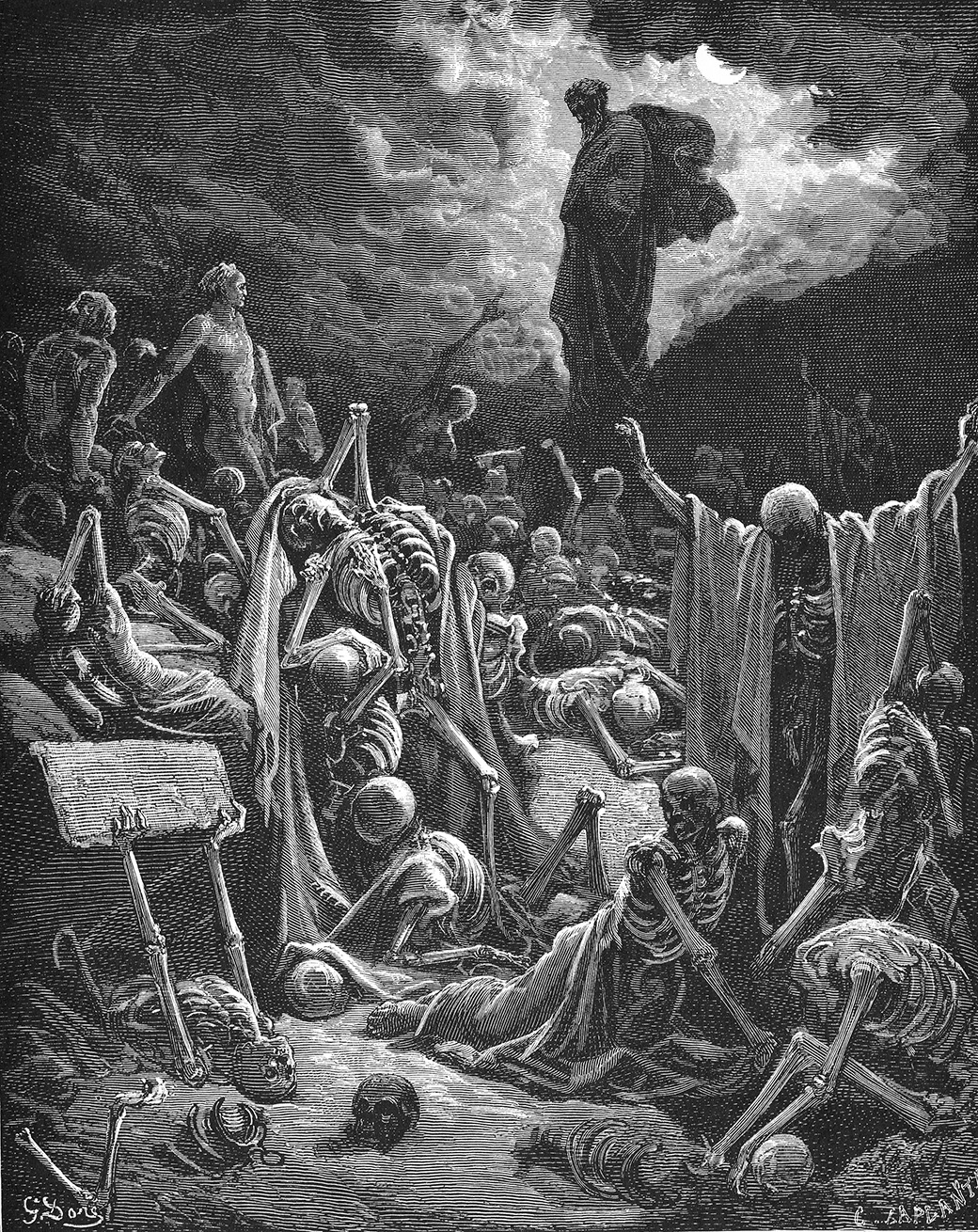

The full context of this scene in Ezekiel, chapter 37, is that the Lord whisks Ezekiel off to a valley filled with “very dry” bones, people who were clearly dead for a long time. The Lord tells Ezekiel to prophesy to the bones and they will become people again. When Ezekiel follows His commands, note that these aren’t just animated skeletons: “suddenly there was a noise, a rattling, and the bones came together, bone to its bone. I looked, and there were sinews on them, and flesh had come upon them, and skin had covered them.” Then, the Lord prompts Ezekiel to ask for the breath of life to fill them, “and the breath came into them, and they lived, and stood on their feet, a vast multitude.”

So Ezekiel prophesies about the full resurrection, body and spirit, but the Lord also makes a point that this is a metaphor for the life of faith here among his Chosen People: “Mortal, these bones are the whole house of Israel. They say, ‘Our bones are dried up, and our hope is lost; we are cut off completely.’” Remember that Ezekiel was a prophet during the Babylonian Exile, when the Jews were cut off from the “land of milk and honey” where Moses established their lands. So when Ezekiel says in today’s reading, “I will open your graves and have you rise from them, and bring you back to the land of Israel,” he is speaking of a literal return of the nation back to the land of Israel. Yet as Christians, we understand that the Word of God speaking through the prophets is the same Word of God that becomes incarnate in Jesus Christ. Thus we understand Ezekiel’s words through the lens of Christ as well; he establishes the new Jerusalem as the Kingdom of God and himself as the new temple. To rise bodily from the graves of the exiled Jewish people and be brought back “to the land of Israel” is to find life in the hundreds of millions of believers who make up the Church, the Body of Christ, since His Resurrection.

Consistent throughout these levels of meaning — bodily and spiritual resurrection, Jewish nation and Christian Church — is the opposition of God’s will and death. The essence of God is the opposite of death. It is the generative spirit of life.

St. Paul speaks of this in today’s reading, telling the Romans that the Spirit, the Person of the Trinity through Whom Christ was raised from the dead, constantly gives us this power of life. He says, “If the Spirit of the one who raised Jesus from the dead dwells in you, the one who raised Christ from the dead will give life to your mortal bodies also, through his Spirit dwelling in you.” We must dig deep to understand the spiritual wisdom of St. Paul. Filled with the Spirit himself, he is describing a new way of being, one which dispels a preoccupation with death. Before Christ, humanity was so preoccupied with death as the inevitable fact of existence that it ruled their minds, determined their actions, and “deadened” their souls (and continues to do so for those outside of Christianity). Paul’s consistent message in his epistles is that Christ changed all of this. By rising from the dead — moreso, by placing the divine and immortal God into a mortal human form and having that particular human’s selfless sacrifice so overpower death in significance — death need no longer dominate our lives. God came to us in love and gave us His Spirit to dwell within us! He writes, “if Christ is in you, although the body is dead because of sin, the spirit is alive because of righteousness.” Death, for St. Paul, is more of a metaphysical aspect of our bodies and fleshly desires than it is a finality. The only finality that matters to St. Paul is the unconquerable, generative life given to us by God.

This is the point Jesus attempts to make by raising Lazarus from the dead. While this is the greatest of His miracles in the gospels, it seems that the triumph of the sign He gives might be marred by uncomprehending minds. Don’t get me wrong, there is much cause for rejoicing in this gospel reading, but if we follow Christ’s words and reactions closely, we see that John is saying something about the reception of His message.

St. John gives us a number of clues in this chapter that what Jesus intends is flying over the heads of those with him. John signals the importance of Christ’s message at the beginning of the chapter: Jesus says, “This illness is not to end in death, but is for the glory of God, that the Son of God may be glorified through it.” The point, in other words, is “the glory of God,” not how awful death is. This is why we hear the curious logic: “Now Jesus loved Martha and her sister and Lazarus. So when he heard that he was ill, he remained for two days in the place where he was.” What type of healer stays put when he hears that a loved one is ill? An earthly healer bound in mind and spirit to the finality of death, that’s who. But Jesus, that is, God incarnate, will show His love for Lazarus and his sisters by opening their eyes to the fact that death isn’t the real finality. Or at least He will try to have them see this point.

Several times he tries to tell his apostles that he’s going to wake Lazarus from his sleep. They first miss the point by saying “Master, if he is asleep, he will be saved.” As if Jesus needs a reminder of the final judgment and salvation of the righteous! Why does Jesus say “sleep”? If we try to understand the world through His eyes, death is just sleep by another name — it does not hold the same frightening finality and inexorable dread that it does for us. Jesus tries to be more direct. “Lazarus has died. And I am glad for you that I was not there, that you may believe. Let us go to him.” Then, the sad Eeyore that is Thomas says gloomily, “Let us also go to die with him.” I can just imagine the suppressed eye roll from Jesus at this weird misunderstanding of his words, as if they were going to emotionally “die” with Lazarus while sitting shiva with Lazarus’s sisters. Jesus’s message will continue to be clouded by this emotional response we have to death.

We commonly associate Martha and Mary with the famous episode in St. Luke’s gospel when they welcome Him into their house for a meal. Years of sermons have impressed upon us that Martha represents the busy believer who is caught up in the rituals of service while not basking in the Spirit right in front of her. Mary represents the opposite: choosing to bask in His presence and let other tasks slide. But this isn’t Luke’s gospel. Here, St. John perhaps gives us a reverse picture: if anything, Martha is closer to appropriately accepting Christ and what He signifies than Mary is.

First clue: Martha comes to meet Jesus outside of town “but Mary sat at home.” Martha says that if Christ had been there Lazarus would not have died. Many have tried to read some type of chastisement in this statement, but I’m not sure the context supports it. She immediately follows this statement with a profession of faith that God will answer any of Jesus’s prayers. The sum of her statements seems like she laments that he was not there but respects his power and authority. Jesus tells her that Lazarus will rise, and her response is similar to the apostles’: “I know he will rise, in the resurrection on the last day.”

Jesus patiently responds with one of the more memorable lines from the gospels: “I am the resurrection and the life; whoever believes in me, even if he dies, will live, and everyone who lives and believes in me will never die.” Jesus accomplishes much, theologically speaking, in this response. First, he takes her belief in the resurrection and makes it immanent in His presence. It is now, not later. Second, he blows up our traditional understanding of death and life. How can someone live “even if he dies”? How can a person of faith “never die”? Let’s recall that Jesus first refers to death as “sleep”. It does not hold the finality that we give it. In this passage, he is saying that the life He gives is way more substantial and significant than this sleep we call death. Plus, in Him this life is here now; we need not wait until the last day.

Martha seems to get it. He asks her if she believes and she proclaims that she does. She adds, “I have come to believe that you are the Christ, the Son of God, the one who is coming into the world.” Does she understand the true implications of his coming? Perhaps so! This proclamation of faith is on the order of the famous one that Peter gives Him after His difficult teaching about eating His Body and drinking His Blood in order to have eternal life.

Mary, however, is another story. Martha encourages her to get out of her self-absorbed sorrow and go to see the Lord. When she does, Mary is a blubbering puddle of emotion: “she fell at his feet and said to him, ‘Lord, if you had been here, my brother would not have died.'” This is all she says as she and her companions take to weeping. She is absorbed in herself, in her belief that death holds a significant finality for Lazarus and all of us.

Jesus’s reaction is interesting and has, in my mind, been regularly misinterpreted. There is an issue with translation. Our lectionary says “he became perturbed and deeply troubled,” while the NRSV Bible says, “he was greatly disturbed in spirit and deeply moved,” and the Douay-Rheims Bible says that he “groaned in the spirit, and troubled himself.” What’s the verb here? In the original Greek, it is ἐνεβριμήσατο (enebrimēsato), which literally invokes snorting like a horse. It means “to be greatly fretted or agitated; an expression of indignation” [The Analytical Greek Lexicon, p. 134]. The verb shows that his indignation was internal. The second verb phrase, ἐτάραξεν ἑαυτόν (etaraxen heauton) means “agitated (or troubled) himself.” So, this being perturbed and troubled is clearly directed inwardly. Why?

He asks them where Lazarus has been laid and after they say, “Come and see.” Then the shortest of verses (verse 35): Ἐδάκρυσεν ὁ Ἰησοῦς. Jesus wept. The verb, a form of dakruo, means a quiet, silent weeping, and is only used for Jesus in the entire New Testament. Some of the people note his weeping as a sign of how much he cared while others grumble about the fact that he should have done something to keep Lazarus from dying. At this, Jesus becomes internally perturbed/indignant again (embrimōmenos).

What do we make of these different emotional states of Jesus? First deeply internally agitated, then silent weeping, then internally agitated again? Fr. George Corrigan, OFM writes online the following analysis:

Two interpretations of embrimaomai in 11:33 have been suggested. First, Jesus was ‘perturbed’ with compassion for Mary when he saw her weeping, and second, that he was ‘perturbed’ with anger. It is hard to linguistically justify the sense of “compassion.” Anger is more consistent with the word’s meaning In the latter case there have been a number of suggestions why he was angry: (1) he was angry because of the faithless weeping and wailing of Mary and ‘the Jews’—they were grieving, as St Paul said, ‘like the rest of men, who have no hope’ (1 Thess. 4:13); (2) he was angry with death itself, the consequence of sin, which caused such pain; (3) he was angry with himself for not coming sooner to heal Lazarus and so prevent his death and the grief it caused Mary and Martha. This last suggestion is unlikely because Jesus knew he was going to raise Lazarus from death. The first suggestion has most to commend it, because the text says it was when Jesus saw Mary weeping like the rest that he became perturbed…but we often rebel at that interpretation.

I tend to agree with Fr. Corrigan here, and although I would say that “anger” isn’t quite the term I would use. Even though the Greek points to the perturbance being internal, I don’t think Christ was angry with Himself. This would imply that He did something wrong, something that He regrets, and we learn especially in the gospel according to St. John that He was fully God, in control, and purposeful in all of His actions. Remember, He intentionally waited to come to visit and said that Lazarus’s state was “for the glory of God.” There is a plan here.

I also don’t think that he’s angry with death and the associated homilies that paint this whole episode in the rhetoric of war — that Christ is doing battle with death. That perspective gives too much power and authority to death, the exact opposite of what Christ is trying to get us to understand. He calls death “sleep;” he is neither scared nor intimidated by death. He states matter-of-factly: “Our friend Lazarus is asleep, but I am going to awaken him.” As if waking someone from a dream. Easy-peasy. His whole point is that we are held under the sway and the spell of death and he has something so much more powerful and significant for us. This isn’t battle, this is swatting away the fly. It is the sizzling away of the water droplet in the awesome purifying presence of God.

So, we are left with the first option that Fr. Corrigan presents (or maybe other options that the Word of God is waiting to plant in our hearts with contemplation). There might be an internal perturbation because Jesus is seeing the sad necessity of his Passion and death, which is coming next in the gospel. Is this a frustration with Mary and the weepers? Maybe. Perhaps it’s a frustration with the state of humanity, so captive to the thrall of death that they can’t see the alternative even when God is present with them. After all, Luke tells us He also weeps over Jersualem and their pigheadedness in not accepting Him.

The weeping and the internal agitation are not so opposite (at least one scholar has been so afield as to suggest that Jesus was bipolar!). In my mind, the agitation is the power of God surging passionately in Him, a gut-like reaction to the thrall of death he finds in humanity. The silent weeping is His humanity, also fully present in Him, and it is sandwiched between these surges of embrimaomai to remind us that our love and emotion comes from God and returns to God. The surges of embrimaomai embrace our human affections in a power that is not from humanity; it is from God and it agitates to release us from the thrall of death.

So, I’d replace “anger” in this examination of the passage with a “gut-like surge, the passion of God’s rejection of death.”

As we finish the gospel reading, we see that even after they have come to the tomb and Jesus asks them to roll back the stone, Martha, the one who seems closest to believing and understanding Him, balks, saying that there will be a stench. He replies, “Did I not tell you that if you believe you will see the glory of God?” We hear no more about a stench, even when Lazarus comes out of the tomb. The glory of God wipes out everything that we think we know to be true. No stench, no death, no laws of physics and biology hold sway in the face of God. Jesus emphasizes this fact when He says, “Untie him and let him go.” It’s His beloved Lazarus, whom He just raised from the dead, and does He rush over to hug him and cry tears of joy with him? No. He reinforces his message that we are slaves to our perception that death holds finality over us by saying “untie” and “let go.” This is the New Moses, leading his people out of slavery in a new and much more radical way.

Astonishingly, even at this, we hear that “many of the Jews” who saw this “began to believe in him.” WHAT? Not everyone was ready to throw down their belongings and follow Him at that moment?? Are you kidding me? Perhaps this is what Jesus saw when he wept his silent tears. No amount of work in his mission while alive can convince the people of God’s radical descent to create a new reality outside of death for them.

It will take His own death and Resurrection for people to see the Glory of God.

Pingback: Master of Destiny - his and ours

Pingback: The Mystery, As We Live It - blind men healed