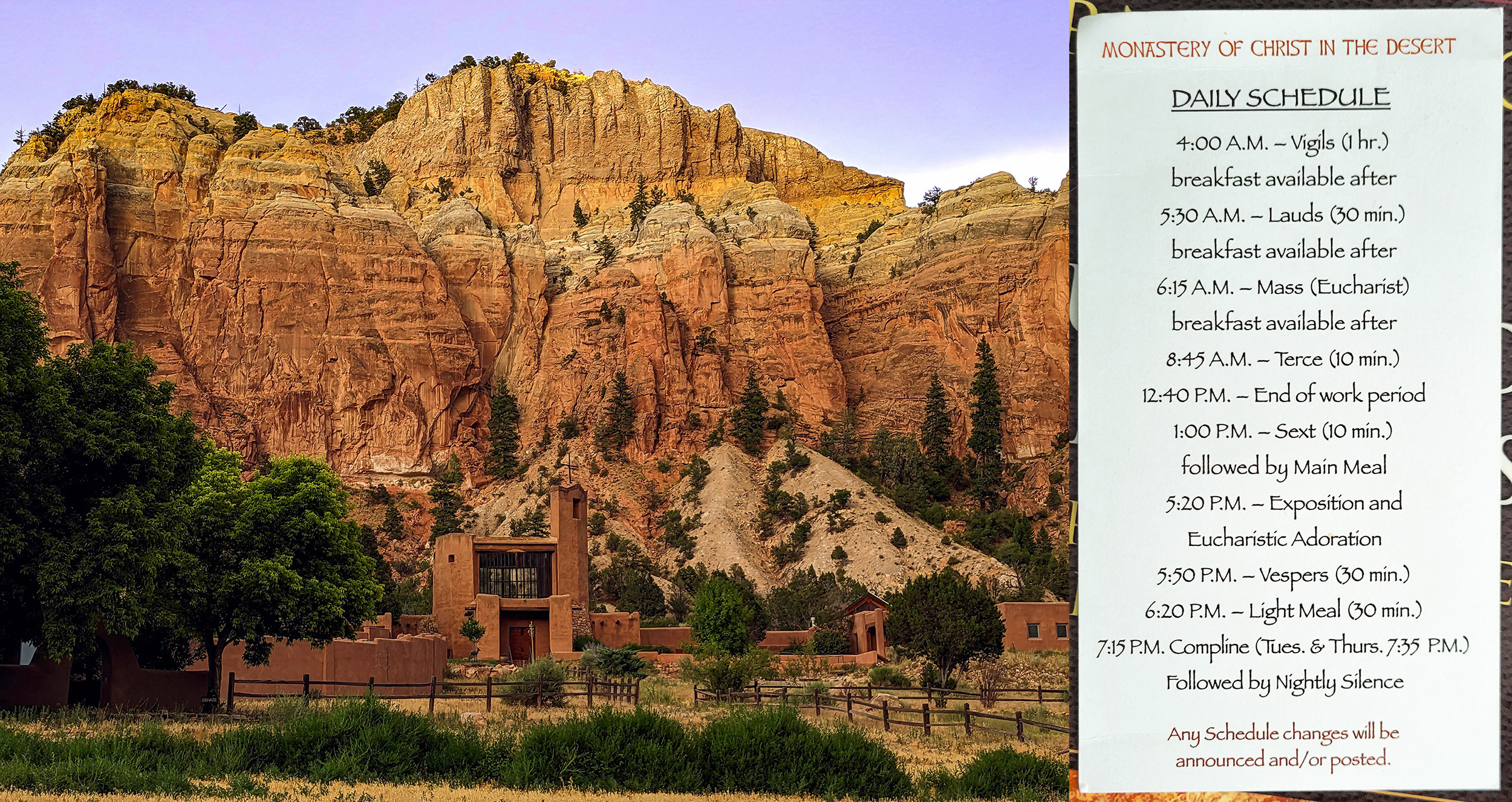

Sixteen miles northeast of the town of Abiquiú, New Mexico, just two and a half miles past the road to Georgia O’Keefe’s famous Ghost Ranch, is Forest Road 151. If you take this unassuming dirt road the length of its 13 miles, the sage, juniper, and cholla cactus flatland gives way to the red rock walls of Chama River Canyon. The further you go, the more dramatic the desert landscape becomes, and by the time you pass the rafting take-out and put-in points and arrive at the Monastery of Christ in the Desert, you’re in the midst of what looks like a mini Zion National Park.

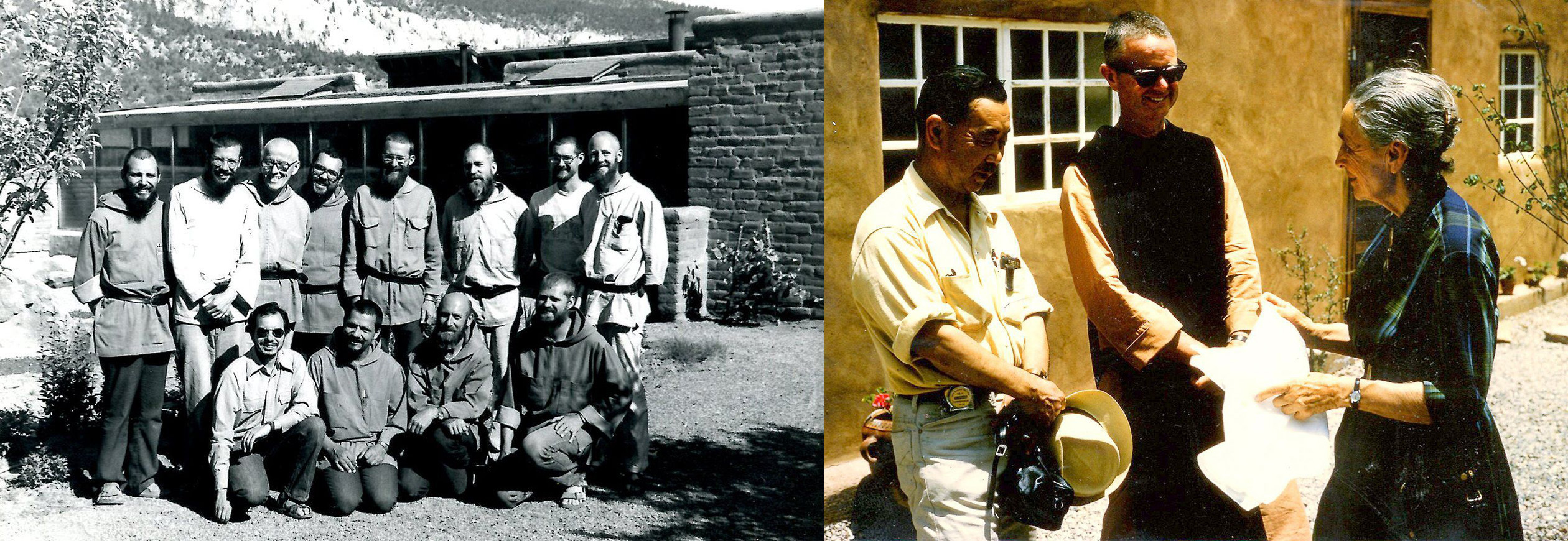

The natural beauty, instead of being the focus of this place, is the backdrop for something more alive, vital, and important. Here, monks pray and work in relative silence, joining their lives to the liturgy, seeking to praise God and know Christ in all that they do. (While inconceivably listed as a “Buddhist temple” on Google Maps, it is in fact a Benedictine monastery.) Founded in 1964, this monastery is a baby (temporally speaking) in comparison to those in Europe. The monks have tried a number of different cottage industries to help support themselves, and today they have a flock of sheep, 50 chickens, a donkey, and four horses, as well as a thriving gift shop for visitors. It is remote, so they create their own electricity thanks to solar arrays (diesel generators did the heavy lifting in past generations), and they are very conscious of water and energy usage.

Hospitality has been a part of the Benedictine charism since St. Benedict wrote his Rule for monks and founded his first monastery in Subiaco, Italy in 529 AD (1,494 years ago!). In the Rule of St. Benedict, he writes, “Great care and concern are to be shown in receiving poor people and pilgrims, because in them more particularly Christ is received…” (53.15). Hospitality is provided not only in the form of food (“the abbot’s table must always be with guests and travelers” [56.1]), but lodging as well, since St. Benedict, speaking of the guesthouse, says that “adequate bedding should be available there” (53.22). Thus, travelers, pilgrims, vagrants, what have you, all find welcome at Benedictine monasteries.

The Monastery of Christ in the Desert welcomes a steady stream of pilgrims, retreat-seekers, and vacationers, thanks in part to the famous American monk Thomas Merton who made mention of this monastery as a wonderful place. Suzanne and I have stayed there twice and we’ve encountered a huge range of fellow guests: Catholics, atheists, Protestant pastors, Jews, retirees, hippies, and discerning priests.

Each person has a different reason for coming, different expectations, and different ways of participating in the Benedictine life. Some use it mainly for rest and relaxation in a beautiful setting. Suzanne and I go for spiritual rejuvenation, embracing the ascetical life of silence, reduced calorie intake, work, and prayer. Chanting the Divine Office with the monks 4 years ago was so joyful and meaningful that we decided to commit to the Lay Dominican path as a way to being more devoted to Christ in our lives.

So, we planned another week at the monastery and have just returned. I had an unexpected and extraordinary experience there – this is my story.

Peace and Disturbance

We had plenty of time to prepare ourselves for the silence. We drove down from Salt Lake City, breaking up the 10-hour journey with a camping spot outside of Mesa Verde National Park, where a vicious storm rocked us to sleep in our rooftop tent. I was looking forward to the challenge of not speaking much for 7 days straight, especially because my last experience at the monastery showed me that silence can be a mind-opening experience in today’s world. I realized this time, like the last, that so much of what we say on a daily basis really doesn’t need to be said. We tend to be chatterboxes, mimicking an information- and entertainment-obsessed culture.

The one time I found the silence uncomfortable was during meals at the guest refectory, a room with 4 tables, each hosting 6 large, comfortable wooden chairs for the guests. Maybe it’s because I felt like being courteous and was also curious to know my fellow pilgrims’ stories, but being silent felt contrary to my inclinations. Perhaps that’s the point – humility in the form of radical respect for others’ space. In any case, after flashing a smile at these strangers across the table, we all just sat there shoveling in food and trying not to make more awkward eye contact.

We settled into a rhythm – walking from our room in the Ranch House up the pebbled path to the chapel, the crunch of our steps loud in the air. The chapel was always bright, even at 4am Vigils when the waning moon lit the path better than any flashlight yet the chapel blinded. It was an appropriate sign of the light of Christ, banishing the darkness of sin and the terror of the night. We chanted out of their prayer books, joining our weak and stumbling voices to the monks’ practiced ones. We took our cues from them – cadence, standing and sitting, bowing, and being patient with it all.

When the Divine Office was prayed, we either left the chapel to return to our room or walked over to the main building with the gift shop, Guest Master’s office, and the refectories where we ate. Depending on the time of day, we might head there for early morning coffee, to receive our morning work assignments (optional for guests), or to eat our main or light meals. Suzanne and I also took a morning walk down the road leading to the monastery in the morning and later in the evening.

The heat of the first few days was intense while the nights were blessedly cool. Our thick-walled room became a cool refuge throughout the days, when we would read for hours on end and nap in the hot afternoon. At night, with the windows wide open, we would fall asleep to the sound of the branches from the big, 7-trunked boxelder tree scraping on the wavy metal awning over the Ranch House walkway. We might sleepily tiptoe past the other two Ranch House rooms to get to the bathroom on the end, and try not to let the screen door bang shut when coming back.

We settled in and I noticed that I became a little more solid, a little more peaceful and grounded each day.

Friday was the first day we were there for Mass, which happens in the morning right after Lauds. To my delight, I saw that the priests had prepared a chalice for the monks and guests and offered the Blood of Christ during communion as well as the Body. I immediately felt drawn to receive the cup during communion but told myself I would wait until Sunday when we were celebrating the Feast of the Transfiguration.

Why wait? First, I think COVID did a psychological number on Catholics. Most, if not all, Catholic churches stopped offering the Blood of Christ as a precaution in the face of infectious disease that could be spread by a shared cup. This makes very good practical sense, but we unavoidably came to associate the precious Blood with getting sick. Of all the contrary notions! So, I think I had an initial reluctance out of the 3-year-old habit of being afraid of contracting a virus.

Second, one of the ascetical privations I wanted to undergo was avoiding alcohol for that week. Suzanne and I have a more “European” approach to alcohol, enjoying wine with nearly every dinner. I felt like a break was overdue and even though a tiny sip of the Blood of Christ does not really count as imbibing, I’m sometimes too punctilious. So, I gave myself a few days of absolute abstinence.

That being said, I was very much excited to receive the Eucharist under both species again. I hadn’t since the start of the pandemic. I have Dominican priest friends who actually see the demise of offering the cup at Mass as a good thing – it’s not standard practice outside of the USA, and it is seen as odd by those who grew up and/or trained for the priesthood outside of the US. After all, we are taught that receiving just the Body of Christ does not diminish the sacrament one iota, and receiving under both species does not somehow increase the reception of Christ. But, even my Dominican priest friends have discussed how receiving under both species might be reintroduced to help signify the solemnity of a feast or special day on the liturgical calendar, so there still seems to be something special there.

So, I sat with a measure of anticipation for Sunday Mass. And that’s when things got a little weird.

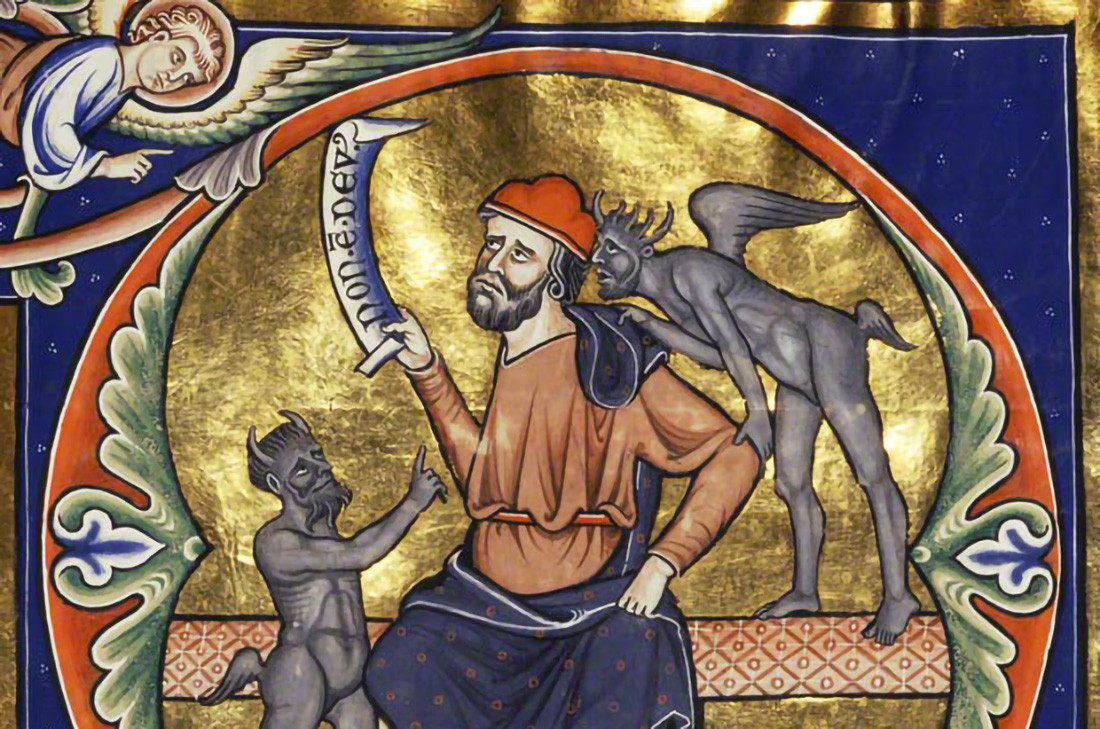

On Friday night, I was having some trouble getting to sleep. In that in between time, when you’re not asleep but you’re definitely not wide awake, I had a vision of myself going to Communion and grabbing the chalice when it was offered to me. I chugged it down, tipping it far back and spilling it down my face and shirt. I heard some wild laughing, encouraging me to guzzle it down. I awoke with a start, horrified at what I had done. That was awful I told myself, knowing I should (and would) never do such a thing. In the back of my mind, I immediately identified this scene with gluttony, and wondered if my subconscious was telling me that I only wanted the sacrament because I wanted some wine. That can’t be true I told myself, it’s not about the wine. But a seed of doubt had been sewn about whether I was approaching the sacrament in the right way.

After some shaky breaths, I tried to coax myself back to sleep. I even said a little prayer to my guardian angel to help me get to sleep peacefully. I should say that I never pray to my guardian angel. In fact, I’ve always regarded guardian angels as a bit of Catholic folklore, made worse by sappy figurines and overly romantic angel depictions on baptism cards. But, I read a lot about the Church Fathers and several early mentions of guardian angels made me take them more seriously. First, we see St. Jerome (c.342-420) write, “how great the dignity of the soul, since each one has from his birth an angel commissioned to guard it” (Comm. in Matt., xviii, lib. II). Then, we have Pseudo-Dionysius the Areopagite (c.500) define the Nine Choirs of Angels, the last of which contains those who are most concerned with human affairs, i.e., guardian angels. And if that wasn’t enough, Jesus himself says, “Take care that you do not despise one of these little ones; for, I tell you, in heaven their angels continually see the face of my Father in heaven” (Mt 18:10). OK, I tell myself, seems like there’s evidence in scripture and tradition that maybe I should be taking this more seriously. And who doesn’t want some spiritual help?

This might be a good time to share what I brought to the monastery for reading material. We have been studying David Fagerberg’s Liturgical Asceticism in our Lay Dominican study, and had recently covered his chapter about the Desert Fathers who retreated to the desert in the early centuries of Christianity to gain control over their passions and engage in other spiritual warfare with demons. I brought a few Dominican texts from Pinckaers and Lombardo to better understand our Dominican understanding of the passions and desire. I also brought Bernard McGinn’s The Foundations of Mysticism book, which I was halfway through – enmeshed in early monastic figures who wrote of transcendental experiences of unity with God, beyond language’s ability to describe, when the unknowable divine essence is somehow beheld or experienced, often in just brief glimpses of time.

All of this to say that I was enmeshed in desert asceticism and early Christian mystical experience, a time when spirits, angels, and demons were seen as very real.

So, I asked for a little help in finding rest. Next thing I knew, I was back in front of the priest, receiving the Blood of Christ, only this time when I tipped the cup back, a dark maroon, viscous liquid entered my mouth and throat. It was actual blood, and I was choking and gagging on it. A deep, malevolent voice sounded in my ears, “if this is what you want, here you go, have it!” This time, I sat up with a start, very upset. This felt wrong and I had no idea where such a nasty image would come from nor why. I felt like I couldn’t control the images that were coming into my mind and that was very upsetting. I figured that I needed to do something more heavy duty in terms of prayer and I’m not afraid to admit that in my distress I mentally uttered the only thing that came to mind – a scene right out of the Exorcist. Knowing the great importance that our tradition and Orthodox Christians place in the name of the Lord, I said in my head By the Name of Jesus Christ, Our Lord and Savior, be gone from my mind you demons!

Writing it down makes it seem kitschy. It’s hard to describe that feeling of being besieged by profane thoughts that aren’t my own, that are out of my control. Maybe people who hear voices in their head feel that way. In any case, I said that with conviction, then recited the Jesus prayer a few times, Lord Jesus Christ, Son of God, have mercy on me, a sinner. By the time I finished these, I had calmed down and lay back to surrender to sleep and see what came next.

I slept soundly through the night.

But, the next day I was unsettled about whether I should go to receive the cup on Sunday. I had a day to let that experience percolate, and I had fairly made up my mind that maybe it was a sign that I shouldn’t go to receive the cup. We had been thinking much over the past few years about receiving Communion in the right state of mind, heart, and body. That is, without any type of grievous sin, having fasted for at least an hour before Mass, and having prepared ourselves over the course of the liturgy to be truly repentant, focused, and receptive. Something about those semi-dreams, those visions, made me feel like either I had sinned somehow in the way I thought about the Blood of Christ or perhaps I simply wasn’t in “right” mind to accept the cup if I was putting so much emphasis on it.

So, when Mass came on Sunday, it was still in the back of my mind to simply receive the Body of Christ and forgo the Blood. It was the Feast of the Transfiguration and I contemplated the great gift God gave the apostles in the vision of the Transfiguration, Christ in all his glory. It was something to give them hope in the dark days after the Crucifixion and even between the Ascension and Pentecost. An amazing mystical truth given to the Church. Before long, the liturgy had progressed to the Eucharist, and I even remember a small voice bartering with me in my head, offering COVID-influenced logic: if too many people go to receive the Blood before you, then just bypass it to avoid possible infection. Oy!

But as I approached the priest, it simply felt right to partake in Christ on this great feast in all of the ways he was offering himself to us and the Father. So, I accepted the Blood of Christ offered to me, a light red wine with a piece of the co-mingled Body floating in it, sweet and rich on the tongue, and warming in the esophagus as I went back to my seat to kneel in thanks. And I was struck with the most amazing sense of rightness. I was as positive as I was about the sun in the morning and my feet on the gravel path that Christ had entered into my body and perfected me. For that moment, I was made whole and warm in God’s presence, and I knew that this was a resounding confirmation that receiving the Body and Blood of Christ was right and good. Of course it was! How could it not be? I thanked God as I knelt and a profound sense of well-being swept through me, the grace of God. I was probably smiling like an idiot.

After Mass, I whispered to Suzanne that I had experienced a really profound Eucharist at Mass. She smiled and said, “good!” I said no more.

On Monday, though, during our evening walk at which we had given each other the go-ahead to talk since we wanted to discuss our readings and experiences (and we’re gabby Dominicans), I spilled the beans on the whole story. Another day of reflection had distilled some things for me, and I wanted to tell her about them. I explained that I had been excited to receive the Blood of Christ for the first time since 2020, but I really felt that a demon (demons?) had planted doubts in my mind that Friday evening. I shared how I had prayed to my guardian angel and then to Jesus to combat these demonic thoughts and how that seemed to work. Then I explained how they even sought to dissuade me just before Communion, but that my profound experience with the Eucharist almost seemed to be a spiritual encouragement or consolation from God for pursuing the good and fighting the distractions and temptations of the devil.

“That is really amazing,” she exclaimed, “because it totally mirrors what I’m reading in The Screwtape Letters right now!” (referring to C.S. Lewis’s classic short book, which I hadn’t read yet).

I was relieved on a couple of levels. I admit to being a bit sheepish about the whole affair. I have told people that I believe in angels and demons as part of the faith we have received, but I’ve never attributed specific, personal experiences to them. It was a nice surprise to find that someone as great as C.S. Lewis presented angels and demons along similar lines as what I had experienced.

We talked some more about it. “I’m actually hesitant to even be saying this out loud,” I said, “because what if I start reading into everything and get completely overwhelmed by a spiritual battle between angels and demons. I feel like I’d go off the deep end.”

“That’s just what the demons want you to think,” Suzanne said slyly.

She was right. It was the same tactic of dissuading me, of diverting me from the good and the true, that they had used a few days earlier.

What do I make of this? Well, I feel blessed to have had my first experience knowingly discerning spirits active in my life. I think we all do this unknowingly. When we are guided by our consciences to make good decisions instead of bad ones, we are navigating the dangerous turf of spiritual battle. When we master and guide our passions to only help things and ourselves reach our proper and good telos, or end purpose, then we are doing the same. But the desert, the silence, the study, the concentrated focus on God and my own response to Him – well, those things yielded something completely new for me. I became aware how as a spiritual being myself, I am influenced by other spiritual beings. This is quite apart from bodily senses – I found that as I was more slow and aware in my mind and heart, it was here that the spiritual life was being contended. It is in my thoughts, my motivations, my feelings and urges that I should be more aware of how I am progressing toward the good with the help of grace or whether I am perverting the natural good of things and myself thanks to the work of demons.

I think this is something very important to be aware of. We are very used to thinking of ourselves as autonomous beings heroically making our own way to God or tragically falling from grace. But, in fact, we are caught up in an inexpressibly vast drama of God’s love for creation, with spiritual forces more powerful than us. It is only by the unmerited and unexplainable love of God for humanity that He deigned to take our form and provide us with a special way back to Him.

There are two equal and opposite errors into which our race can fall about the devils. One is to disbelieve in their existence. The other is to believe, and to feel an excessive and unhealthy interest in them.

-C.S. Lewis, preface to The Screwtape Letters

A Note to Skeptics

Many who ready this may be skeptical of my experience, and I certainly understand. Are demons and angels real? In 2023, demons and angels are nothing but the stuff of fantasy and television series. I can hear the very learned psychiatrist and atheist friend in my book club, who we call “Michael the Elder,” saying, “this is just psychologizing of the emotions and dream states, pure drivel!”

Here is an important point: modern neuroscience has done an amazing job of describing how the brain works. Indeed, scientists can even identify chemicals and neuropathways involved in emotional states and religious-type experiences. I love reading these studies and gaining insight into the amazing machines our bodies are. But neuroscience can only understand the mechanics of the brain and psychology can only describe the strivings of intellect and reason. They merely guess at why emotions and visions happen. As far as the content and significance of them, these sciences try to apply systems of mythology and sense-making from people like Freud, Jung, Lacan, etc.

For people of faith, we engage a part of ourselves beyond the intellect, namely the soul, to probe and interact with the world beyond the senses. After all, it is not my sight, hearing, touch, taste, or smell that leads me to believe in Jesus Christ as the gate to everlasting life (although all of those are lovingly engaged in our celebration of the liturgy where our souls and bodies rejoice in the Lord). No, it is trust in the revelation of God to humanity over millennia in the form of prophets, religion and scripture. If that was not enough, He gave us Himself as a real, historical person in flesh and blood to not just help us believe but also to raise us up spiritually and bodily to be with Him.

So, we’re not so different, atheist psychiatrists and me. We both trust in something (or have faith in something). They trust secular systems of sense-making from modern psychologists and published observational studies, while I trust a 2,000 year-old sense-making system that engages more than just the intellect.

There is one more issue that must be addressed: dismissing an experience like mine as superstition. Most of us would agree that the word “superstition” means belief in supernatural causes for which there is little evidence. Often, though, I think this word is used more like name-calling than honest evaluation of a person’s metaphysics. We undoubtedly live in a modern era where science and technology have transformed our physical lives so completely that discussions of spiritual beings feels archaic, medieval, maybe even cute and diverting. Why, then, do people continue to grope for faith on their deathbed? No matter how we try, we can’t seem to escape the question of whether something in us (a soul) might persist after death. Perhaps smart phones, brain surgery, and AI are the real diversion. Are we so busy making our lives comfortable and convenient that we’ve lost sight of the great human drama of life and death, oblivion, heaven and hell? These become important when everything is swept aside and we face the grave. This is when we ask if there might be more, when we desperately try to search with some faculty in us beyond our intellect – our soul like a decrepit cow kept caged its entire life and unable to even stand.

In fact, the weight of human history is on the side of faith and the spiritual. These are things we seem to have been created with, and maybe even created for. If we lift our heads out of a 100-year-old ascendance of science, technology, and atheism, we might be surprised to find an astonishingly sophisticated faith-based metaphysics that encompasses not just emotion, psychology, and earthly meaning, but spiritual forces, development of the soul, and peace with our eventual death. And this is anything but “belief in supernatural causes for which there is little evidence.”

800 years ago, codifying the Christian sense-making system along rational, intellectual lines reached a climax with medieval scholasticism. The greatest of the scholastics, the Angelic Doctor St. Thomas Aquinas, gifted us with a way of understanding how we can develop our whole selves in order to be ready for the grave when it comes. To the point of the experience I’ve described above, St. Thomas synthesizes bodily senses, emotions, passions, cognitive evaluation, memory, and intention within a broader environment of virtue, spirit, and striving for the good. He respects our faculties enough to evaluate and counsel how we might deal with complex feelings and visions rather than blow them off as dreams or meaningless fantasy. An experience like mine, for St. Thomas, is not the stuff of talk therapy, sleeping pills, or pharmacotherapeutics but of the actionable, vibrant spiritual drama of life and virtue. He would see the temptation towards the improper use of the good and discernment of the proper striving for the good. He wholly accepts the spiritual activity of demons and angels as revealed in scripture.

For me, at least, this is a much more real and full (not to mention exciting and alive) way to make sense of who we are and where we’re headed.

Michael, I truly enjoyed reading about your experience. To know that Suzanne was there to listen ( when the time was right) and reaffirm what you were feeling was correct from what she was reading….what an exhilarating time for you!

What you went through is something to be desired!!!….… I say not for us, but for some of our children and grandchildren. I will pray that they will receive the desire to become more faith filled! Can I ask you to include my request in your prayers once in awhile? Thank you.

You are a blessing to your parents…I can only imagine their gratitude and joy they felt after reading their son’s beautifully written story….

Thank you for sharing this with us.

Nina and Charlie Siggia. (your parents neighbors)