Ash Wednesday: Joel 2:12-18, 2 Corinthians 5:20-6:2, Matthew 6:1-6, 16-18.

Like a thief in the night, Lent is here. So soon, I am tempted to think, must I again pare down my pleasures? On the heels of a pandemic year where we all felt penned in and constrained, Lent can appear as an unwelcome guest. Popular culture tells us that 2020 was the worst year ever and we deserve a break. But was it? And do we really?

I think that many people (myself included) actually found some silver lining in the cloud of 2020. Less time driving my car = less frustration; more quiet = more appreciation of people and life in general; less eating out = less wasteful spending and more healthy meals. Yes, I’m partly suggesting that 2020 was a bit of a long fast in itself, a kind of analogy for seeing how we might find similar silver linings to the privations of Lent. But that’s really backwards and a poor, self-serving way of understanding Lent.

While the word “Lent” comes from old English “lengthen” as applied to the days in Springtime, the Eastern Churches call Lent Μεγάλη Νηστεία (Megali Nisteia), which means “The Great Fast.” And while the promise of Christ’s Resurrection does approach like the slowly lengthening springtime sun, I see a deep significance in setting myself up for Lent by thinking of it as the Great Fast. Appropriately enough, today’s Ash Wednesday readings are all about fasting and how it was used by Jews and Christians alike as a bodily way of relating to God. And here is the crucial missing thing from our pandemic year analogy: God is an essential part of the fasting equation. Without God, fasting has zero spiritual benefit and is pointless. Let’s truly reflect: how much of 2020 was about meeting God and how much was about us and our inconvenience? We cannot let Lent be just a continuation of the emotional struggle of living in a pandemic. It can be so much more.

Let’s consider the great commandment, gift, and tradition that is fasting. Commandment? Yes, according to St. John Chrysostom, “Fasting was the first commandment God gave to man.” He points to the Book of Genesis: “And the Lord God commanded the man, ‘You may freely eat of every tree of the garden; but of the tree of the knowledge of good and evil you shall not eat,'” (Gen 2:16-17a). I appreciate Chrysostom’s close reading here; God could have commanded Adam not to look in a special cavern, not to swim in a special pool, or not to say a certain word, but instead he commands Adam to have control over his appetite and desire. There have been many great essays written on the significance of the fruit of the “tree of knowledge of good and evil” being the fruit that belongs only to the Creator Himself and how Satan’s great temptation for us is to live as gods, but today I am struck by a more simple point. Chrysostom reminds us that God’s first commandment is to have bodily restraint in terms of food. On this simple level, when we fast we can reconnect with a primal obedience to our Lord and Creator.

In today’s first reading, God speaks through the prophet Joel to the Israelites: “return to me with your whole heart, with fasting, and weeping, and mourning; Rend your hearts, not your garments, and return to the LORD, your God.” He is talking to Adam’s ancestors, whose original father unlawfully broke his fast, and the fasting God urges upon them is a sign of their atonement, as are their tears and broken hearts. Fasting helps to mark the sincerity of their conversion back to God. And God wants His Chosen People to publicly and jointly take part: “Blow the trumpet in Zion! Proclaim a fast, call an assembly; Gather the people, notify the congregation.” Fasting unifies the people before their God and Master. Contrast this with our current secular culture where fasting is simply seen as another dieting option, a way to improve how you look or maybe how you feel. How strikingly different! Fasting in our faith tradition is certainly a personal response to God, but it is also a communal act of a people aware of their dependence upon God’s mercy. Remember the story of Jonah and the Ninevites. He (reluctantly) went to Nineveh to preach that they would be destroyed unless they repented and after just one day, “the people of Nineveh believed God; they proclaimed a fast, and everyone, great and small, put on sackcloth” (Jn 3:5). More: “When the news reached the king of Nineveh, he rose from his throne, removed his robe, covered himself with sackcloth, and sat in ashes. Then he had a proclamation made in Nineveh: ‘By the decree of the king and his nobles: No human being or animal, no herd or flock, shall taste anything. They shall not feed, nor shall they drink water'” (Jn 3:6-7). Here we have a great, communal fast and repentance — a heartfelt response to God’s call. This story is an important illustration of what the Jewish faith calls teshuva, or the ability to repent and be forgiven by God: “When God saw what they did, how they turned from their evil ways, God changed his mind about the calamity that he had said he would bring upon them; and he did not do it” (Jn 3:10).

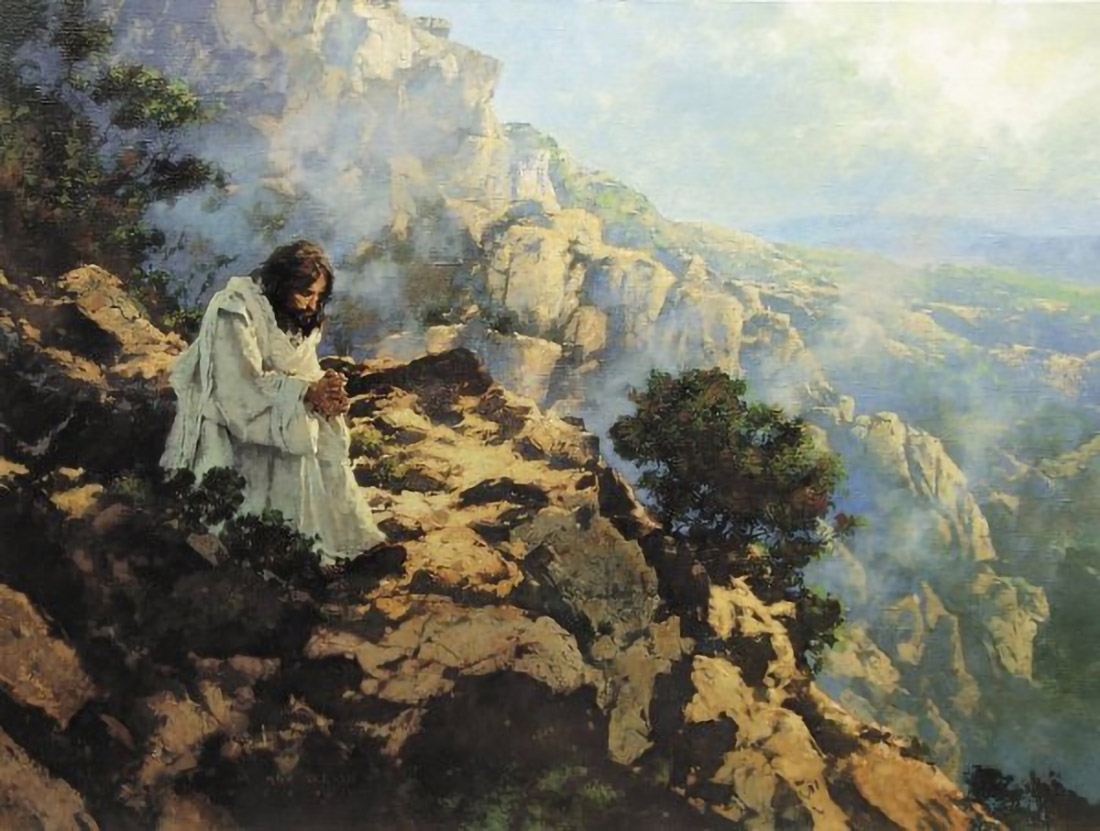

Teshuva is a persistent theme throughout the Bible, and fasting is integrally tied to this heartfelt repentance. Nearly all of the prophets speak of fasting, often in the context of teshuva. Notably, Moses fasts for 40 days and nights, as does Elijah and Jesus, the Son of God Himself. (And we see these three great prophets together on the Mount of Transfiguration). John the Baptist subsists on wild locusts and honey. As we consider these prophets, the mouthpieces of God, we start to see that fasting is tied to more than just repentance and a plea for mercy. Fasting is a way for Moses to prepare to be in the presence of the divine. Fasting is a way for Elijah, Ezra, Esther and many others to ask for God’s favor and help with their specific problems. Fasting is a purification and a way for Jesus to achieve spiritual fortitude as He is tempted by the devil. Our great prophets teach us that fasting strengthens us spiritually — particularly our bond with God the Father — even though it seems to be weakening our bodies. Thus, Chrysostom can write, “Fasting of the body is food for the soul.”

In today’s gospel reading, Jesus instructs his disciples not so much on the benefits of fasting (this was a given, known thing for Jews and Gentiles alike in Jesus’s time) but on how to fast effectively. He lays out the path to being a humble, earnest child of God: “Take care not to perform righteous deeds in order that people may see them … when you pray, go to your inner room,

close the door, and pray to your Father in secret … when you fast, anoint your head and wash your face, so that you may not appear to be fasting, except to your Father who is hidden. And your Father who sees what is hidden will repay you.” For a Jewish culture at times obsessed with purity and outward signs of worthiness, Christ’s words are a significant re-ordering of their priorities. More importantly, He presents them with a profound revelation of who God is. This Father of ours is an intensely personal one, someone who is most interested in the secret, hidden, most private moments He shares with His children. Jesus’s words also reassure us that humans are fundamentally spiritual beings — much more than just physical creatures who act within a society, when all of the “doing” is done and we are alone, our Father is with us. He has blessed us with a soul that is at the core of our being; He has called us, entrusted us to be His beloved children, living by his commandments and praising Him by sharing his love in the world.

Lent is our time to re-order ourselves to this fundamental truth. It is not the spiritual that should be conformed to the physical — that is, we should not pray when it’s convenient for our physical routine or allow moral judgment and God’s commandments to be casually overridden by physical cravings like rich food or sexual desire. If we are fundamentally spiritual beings first and physical and emotional beings only for a time here on this earth, then the spiritual drive should always come first. The logic of fasting suddenly becomes obvious. We offer to our God a small sacrifice of our physical comfort as we put our spiritual relationship with Him first.

Christians have always fasted; like devout Jews at the time of Christ they fasted two days each week. St. Paul famously accepts fasting as a part of his spiritual conversion: for three days after being struck blind on the road to Damascus he “neither ate nor drank” (Acts 9:9b). Also at his commission at Antioch: “While they were worshiping the Lord and fasting, the Holy Spirit said, ‘Set apart for me Barnabas and Saul for the work to which I have called them.’ Then after fasting and praying they laid their hands on them and sent them off” (Acts 13:2-3). In fact, he tells the Corinthians that his entire ministry has been an acceptance of physical hardship in order to do the spiritual work to which God has called him: “In toil and hardship, in frequent sleepless nights, in famine and thirst, in frequent fasts, in cold and nakedness … If I must boast, I will boast of things belonging to my weakness” (2 Cor 11:27, 30). Drawing upon these great lessons from the Apostolic Age, we see the desert monks emerge a century or two later, feeding upon this same wisdom. They “boast in weakness” (that is, physical weakness) like the lack of food, comfort, sex, etc. because they find that they grow strong in spirit. This monastic tradition has continued through the centuries to this day, with the vows of poverty and chastity that monks and nuns take in their vocation. This is not ritualized masochism! Christ Himself taught us the deep truth about what it means to be human, to have a body, mind, and spirit wrapped up in one being, and how the spirit must shine because it is preeminent in the order of being. Again, let’s not twist this into thinking that the Church sees the body as evil. The Catechism tells us:

The human body shares in the dignity of “the image of God”: it is a human body precisely because it is animated by a spiritual soul, and it is the whole human person that is intended to become, in the body of Christ, a temple of the Spirit:

Man, though made of body and soul, is a unity. Through his very bodily condition he sums up in himself the elements of the material world. Through him they are thus brought to their highest perfection and can raise their voice in praise freely given to the Creator. For this reason man may not despise his bodily life. Rather he is obliged to regard his body as good and to hold it in honor since God has created it and will raise it up on the last day”

(CCC, citing Gaudium et Spes from the 2nd Vatican Council, 364).

I love our theology on the body of Christ. We, the Church are the Body of the divine Christ active in the world, and Jesus has a corporeal body that was tortured and crucified, only to rise and walk in the world before ascending to the Father. The body of Christ is also present in our Eucharistic sacrament, to be taken in by the faithful as spiritual sustenance. There are so many levels upon which Christ’s body is the ultimate example of how human life can transcend this mortal plane, subordinated to the spirit and yet rising in significance specifically because of its lowly state. The body, created from the dust of the earth, is miraculous and good because God breathed life into it. Without that breath and Spirit, the body is just dust. When the origin, the breath of life, is honored above the body, then the human who is a unified body and soul can bring that body to the heavenly plane to dwell with God. Fasting is a way — an ancient and important way — that we can honor God over and above the body.

St. Paul in today’s second reading impresses upon the Corinthians that as followers of Christ, what we do with our bodies matters even more than it did before Christ’s great sacrifice: “We are ambassadors for Christ, as if God were appealing through us … we appeal to you not to receive the grace of God in vain.” What he is saying is that we must carry forward Christ’s teaching and example of how the body can have everlasting life with the soul. We Christians are graced with learning the truth of Christ, which means we are entrusted with passing along the lessons, the charity, the subordination of the body to spiritual realities. We are the Body of Christ and we must uphold the sacred function of that Body in lifting up humanity through humility and charity at the cost of fleeting comforts.

So, it’s Ash Wednesday, one of only two days of fasting that remain in the Western Catholic Church’s liturgical calendar. We really don’t ask much of ourselves these days. Let’s listen to St. Thomas Aquinas remind us of the aims of fasting: “fasting is practiced for a threefold purpose. First, in order to bridle the lusts of the flesh … Secondly, we have recourse to fasting in order that the mind may arise more freely to the contemplation of heavenly things … Thirdly, in order to satisfy for sins” (Summa 147.1). We hear him address our body (bridling lusts), our mind (contemplation of heavenly things), and our soul (atoning for sins). Fasting, in other words, is a triple-threat spiritual practice. But only if done for God! Aquinas’s entire point in this reflection is to show that fasting is virtuous, with the caveat: “An act is virtuous through being directed by reason to some virtuous good.” He lays out the “virtuous good” in terms of body, mind, and soul, but of course the ultimate virtuous good is Good Itself, that is, God.

This is why the term Μεγάλη Νηστεία, Great Fast, is so appropriate for all of Lent. This is not to say that we spend all 40 days in actual fast like our ancient Christian forebears did (although there is a part of me that wishes I would and I could in order to be that much closer to God). It’s that we recognize these 40 days and nights as a time where we are focused on the virtuous good of God, in our bridling of our lusts, in our contemplation of heavenly things, and in our atonement for our sins. The aim and the thrust of fasting can be carried out throughout Lent in each moment when we hold back a rash remark, when we take that idle moment to offer a prayer to God, when we forego something little that would make us “feel good” in order to make someone else feel good or even as just a little sacrifice offered to God to let Him know that we aren’t being ruled by our base earthly desires. This is how we can make all 40 days a Great Fast. And as we do, we realize it becomes easier. That spot of hunger goes away and subsides like a devil thwarted. We realize that we can live and perhaps even thrive without those creature comforts — the potato chips, the time in front of the TV — and instead spend that time reading the scriptures, singing a psalm, praying the rosary, or just reflecting quietly on Christ’s sacrifice, on the Face of God.

My hope is that we allow the Great Fast to wash over us like a giant wave. That we do not resist its current but allow ourselves to be caught up in it – allow the Fast to grip us, determine our direction and our very breath. This is the the first step in giving ourselves to God and allowing Him to bestow His grace in our lives.

Read the reflection from Ash Wednesday 2020 here: Ambassadors for Christ.