Friday the Third Week of Easter: Acts of the Apostles 9:1-20, John 6:52-59.

Today’s readings are two incredibly important passages; one describes Saul’s transformation from persecutor to “chosen instrument” of Christ, and the other gives us Christ’s words that insist upon the literal ingestion of his flesh and blood, which we Catholics likewise insist is present in the Eucharist. What emerges as we hear these readings is a persistent focus on the need for the body, the flesh, to be purified and perfected as we are on our way to salvation.

In the first reading, we find “Saul, still breathing murderous threats against the disciples of the Lord.” He asks the high priest for letters to go to synagogues in Damascus that would give him the authority to arrest Christians and bring them back to Jerusalem in chains. He is zealous in his desire to stamp out the new Way of Jesus Christ. But, like prophets before him (Noah, Jonah), God has radically different plans for him. We are familiar with the story: a light flashes all around him and he falls to the ground (no horse is mentioned, but that has somehow crept its way into the story). He and his companions hear the voice of Christ: “I am Jesus, whom you are persecuting. Now get up and go into the city and you will be told what you must do.”

Paul’s conversion has a significant physical aspect: “Saul got up from the ground, but when he opened his eyes he could see nothing; so they led him by the hand and brought him to Damascus. For three days he was unable to see, and he neither ate nor drank.” Whenever we encounter blindness in our scriptures, we can understand it to signify spiritual blindness, which certainly can be applied in this instance. But note here how the physicality of the blindness reduces Saul from this puffed up, powerful persecutor so someone who must be led by the hand. He becomes absolutely dependent on people, like a child. This is undoubtedly part of the penance of his conversion, and by taking the time to explain this aspect of the story, the author of the Acts of the Apostles is taking on the same insistence of the physicality of our faith that we will encounter in the gospel.

His physical and spiritual dependence is again emphasized when he is told that Ananias, a follower of the Way, will be the one to heal him. Saul is made vulnerable, delivered into the hands of the very people he set out to imprison. And how do disciples of Christ respond to persecutors? They turn the other cheek, they offer love, and in this case, spiritual and physical healing. Again, we hear very physical details about the healing: “Immediately things like scales fell from his eyes and he regained his sight. He got up and was baptized, and when he had eaten, he recovered his strength.” The scales are a physical manifestation of the spiritual mire, the spiritual blindness of this man who was a primary witness of the martyrdom of St. Stephen. It’s as if his sin and self-imposed blockages to the Word of God were crystallized, precipitated out of solution, pulled out like a filter that cleans filthy water. Directly after he gets up, able to see, we hear that he is baptized. Even though this seems to be reported casually, this is no small matter. Baptism in the name of Jesus Christ marked a full conversion of a person to the new Way and a direct rebuke of the chief priests and scribes who had murdered Christ. By accepting baptism, Saul was making a 180-degree turn towards Christ and away from the high priest whose approval he had just sought.

Another aspect of Saul’s conversion is his self-imposed fasting. Fasting was an important aspect of having an appropriate “fear of God” in the Jewish tradition. The fast, or taʿanith, was specifically when atoning for sins, to accompany contrition in the heart, and in supplication during earnest prayer (see our reflection Esther: Model of How to Petition the Father). Any reader familiar with Jewish tradition (which continues in Christian tradition) would understand that Saul would be searching his heart in atonement over those three days and would be deep in supplication and prayer with God. As St. Isaac the Syrian wrote, “When a man begins to fast, he straightway yearns in his mind to enter into converse with God” (Homilies 37, in Ascetical Homilies, 171). Yet once again we are tuned into the physicality of Saul’s conversion, that the once virile man who dragged Christians to prisons in chains had been reduced to a weak, blind, and utterly dependent child. This is just the beginning of the Way of the Cross. As Jesus tells Ananias, “I will show him what he will have to suffer for my name.” A more literal translation of this passage is “I will show him how much it behooves him to [or he must] suffer for my name.” But the point isn’t penance, it’s deliverance from the reign of death and into the salvation found in the reign of God. For Saul is cured of his blindness, he is made strong again at the hand of Jesus’s disciples, he is baptized into the inheritance of everlasting life. It’s simply that the Way of the Cross naturally involves suffering, which the one who suffers comes to understand is nothing more than purification in the Name of the Lord.

Our Church Father Tertullian provides us with a nice way to think about a central truth in our faith. The Catechism of the Catholic Church quotes him as writing: “The flesh is the hinge of salvation” (CCC, 1015). The fuller context of the quote is as follows: “no soul can ever obtain salvation unless while it is in the flesh it has become a believer. To such a degree is the flesh the pivot [hinge] of salvation, that since by it the soul becomes linked with God, it is the flesh which makes possible the soul’s election by God. ” (De Resurrectione Carnis translated by Ernest Evans, 8). Written sometime around 220 AD, this passage summarizes a “take-home message” from Christ’s ministry and the scope of salvation history leading up to it. The flesh is clearly central — as Tertullian put it, a pivot, fulcrum, or hinge — to salvation, a phenomenon of the soul. Let’s unpack this. First, the soul is seamlessly united to the body in this life; the union of the soul (breath of God) and the body (clay or dust of the earth) is what makes me a person. The body is intimately entwined with the soul and thus it is part and parcel of our connection to God as defined at creation. Second, Christ spoke again and again about the importance of accepting God and the Way while alive here on earth, before the death of the body. More than just accepting God, we are called to act with charity towards our fellow humans (charity being a perfect reflection of the outpouring love that is God). In other words, what we do while we have these bodies matters. Our faith in God and our works of mercy and charity secure our salvation. Both faith and works happen while our personhood inhabits the bodies we have been given. Thus, “the flesh is the hinge of salvation” since without the actions of the flesh, salvation could not be secured.

I have to address one other item before we return to today’s readings. The title of Tertullian’s work is translated as “The Resurrection of the Flesh,” and the question inevitably turns to what happens after our death — if we achieve salvation, is our very flesh raised from the dead? This has been debated since the earliest days of the Church. St. Paul has a strong opinion that he relates to the Corinthians: “What is sown is perishable, what is raised is imperishable. 43 It is sown in dishonor, it is raised in glory. It is sown in weakness, it is raised in power. 44 It is sown a physical body, it is raised a spiritual body. If there is a physical body, there is also a spiritual body” (1 Cor 15:42-44). He makes himself even more clear a few verses later: “flesh and blood cannot inherit the kingdom of God, nor does the perishable inherit the imperishable. 51 Listen, I will tell you a mystery! We will not all die, but we will all be changed” (1 Cor 15:50-51). But 300 years later, St. Jerome and St. Augustine insist that our bodies are indeed resurrected on the last day, and the medieval scholastics agree with them. So we read in the Catechism of the Catholic Church a quote from the Council of Lyons in 1274: “We believe in the true resurrection of this flesh that we now possess” (CCC, 1017). But this has been debated up through our contemporary times. St. Pope John Paul II wrote what is probably the most reasonable way to speak of our resurrection and eternal life: “It is always necessary to maintain a certain restraint in describing these ‘ultimate realities’ since their depiction is always unsatisfactory” (General Audience, 1999). In other words, we can affirm that whatever comprises our “person” will rise to have eternal life with God. In this life on earth, our “person” is understood to be a seamless union between soul and body, but will that be the same case (or the same body) at our resurrection? We will only know for sure on the Last Day!

Back to our readings. I am struck by how Christ insists upon the fundamental physicality with which we live our lives “on the Way.” Saul is to become one of the great examples of a man beaten, imprisoned, starved, shipwrecked, and rejected repeatedly while at the same time joyously bringing the light of the Word of God to the world. How can we expect the flesh to endure such things? Who would want to endure such things?

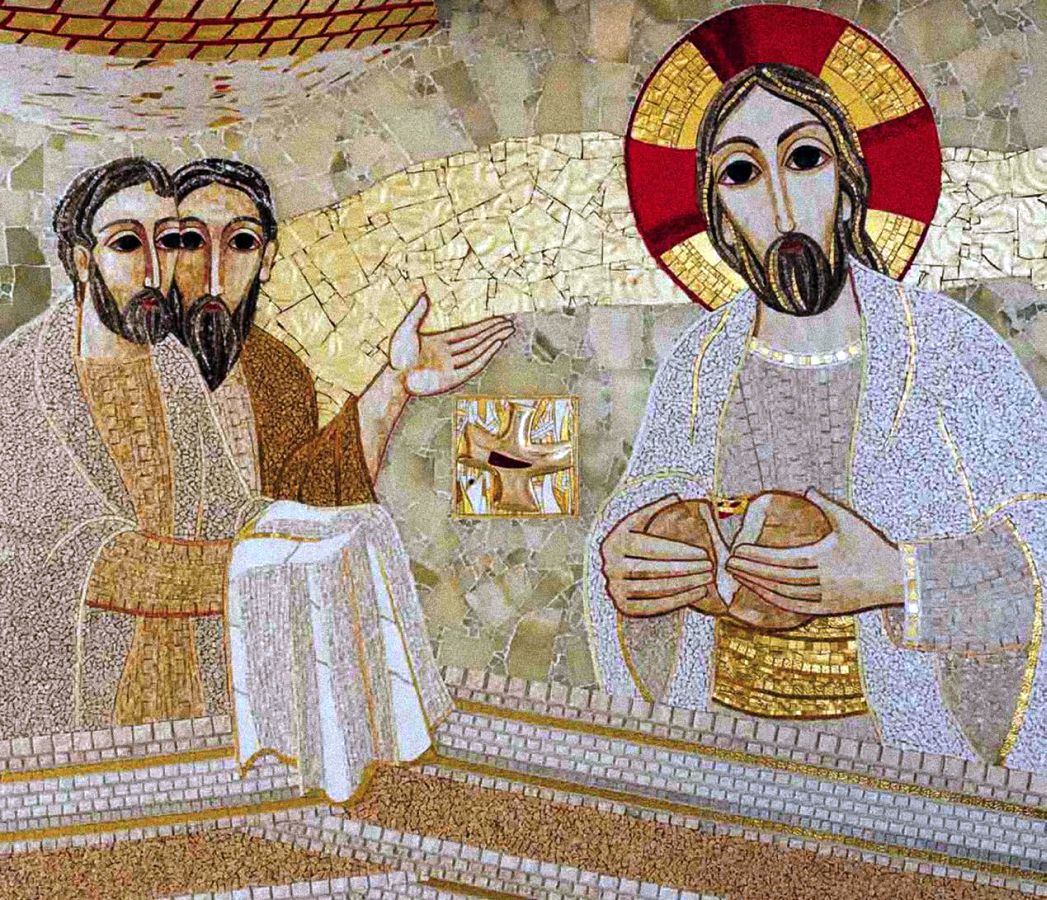

Jesus gives us the answer in today’s gospel, the culmination of the Discourse on the Bread from Heaven: “Just as the living Father sent me and I have life because of the Father, so also the one who feeds on me will have life because of me. This is the bread that came down from heaven. Unlike your ancestors who ate and still died, whoever eats this bread will live forever.” Here is the great promise, the New Covenant. The one who feeds on me will have life because of me. What’s more, this bread that is His Flesh and Blood guarantees life forever. OK, pretty good reason to have our own bodies endure the Way of the Cross. Also, the promise includes a wellspring of life that we must understand extends to this life, not just life in Heaven. This food sustains and uplifts, rejuvenates and expands a person like no regular food can do.

The great question that has splintered groups from the Catholic Church is whether Jesus refers to symbolic flesh or literal flesh. We Catholics believe that He didn’t just stop at a symbolic or spiritual understanding of eating His Flesh and Blood. He says, “my Flesh is true food, and my Blood is true drink. Whoever eats my Flesh and drinks my Blood remains in me and I in him.” This is a response to the Jews saying, “How can this man give us his Flesh to eat?” He doesn’t respond by saying “I am referring to my flesh symbolically,” but instead repeats Himself, rephrases Himself, never losing the stubborn physicality of the message. Of course, His Flesh and Blood is spiritual food, but He also insists that it is His Body, His Flesh and Blood, the same physical thing that He brings to the Cross.

What are we to make of this? Should we be grossed out and turn away like “many of his disciples” after they hear this teaching? Certainly not! We are not cannibals who feast on bloody flesh for flesh’s sake. The Eucharist is an unbloody offering of the flesh, done sacramentally and reverently, where the Holy Spirit is the means and the goal. Christ’s way of giving the Spirit to us through his flesh is an orienting reminder to who we are as Christians, willing to sacrifice our very selves to the Father. It is an insistence that the flesh matters. Just like fasting and mortification of the flesh are ways to purify the body, not in disdain for it but in acknowledgment of its intimate union with the soul, we can see how Christ’s offering of himself as food is another acknowledgment of the importance of our bodies. The body must be nourished by the right food — spiritual food — if it is to be ready to walk the Way of the Cross.

As Tertullian writes, the flesh is the hinge of salvation. We must not hide that, we must exult in that. Our greatest sacrament embraces Christ’s sacrificed Flesh and Blood, brought to the Father with greatest reverence, Who in turn offers it back to us as the Bread from Heaven. Alleluia!