Easter Sunday: Acts of the Apostles 10:34a, 37-43, Colossians 3:1-4, John 20:1-9.

Today’s readings uncover the truly baffling nature of the empty tomb. We rejoice, 2,000 years later because the full revelation of the Resurrection is known. We sing Alleluia! with abandon, but today’s readings remind us that His rising from the dead was unexpected and incomprehensible on the morning after Passover, even for those who believed in Him as the Messiah.

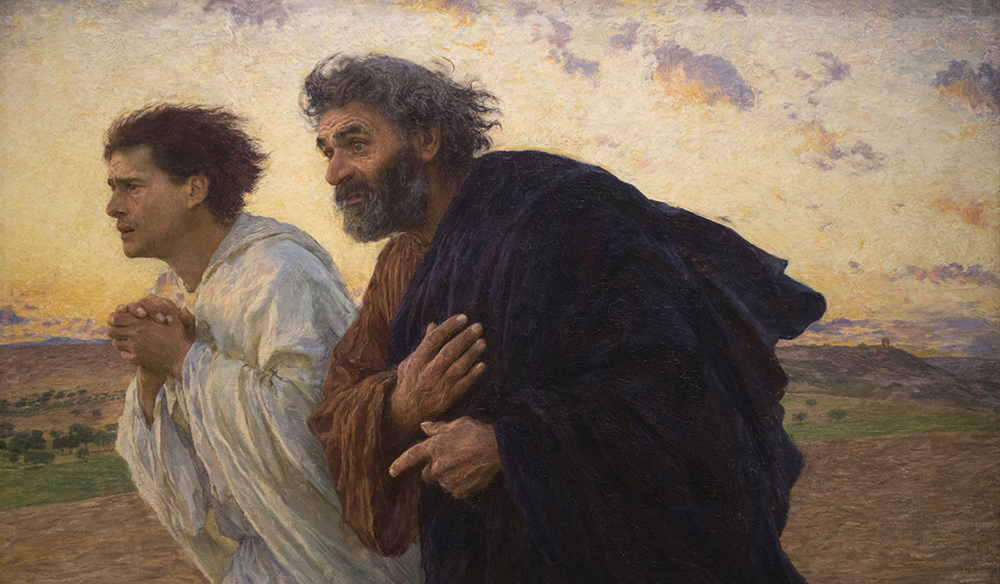

In the gospel, Mary Magdalene, driven by her love of Jesus, goes to the tomb early in the morning after Passover, “while it was still dark.” The darkness is emblematic of the encounter at the tomb for her and, later, Peter and John. Mary is so discombobulated by the sight of the stone that is rolled away that she runs back to the apostles without even looking in. She thinks that someone stole His body: “They have taken the Lord from the tomb, and we don’t know where they put him.” Perhaps the “they” she refers to are the guards, the Romans.

The state of the burial cloths is even more confusing for them. Peter and John see “the burial cloths there, and the cloth that had covered his head, not with the burial cloths but rolled up in a separate place.” This is not the scene of a tomb being pilfered or a simple act of transferring a body somewhere else. St. John Chrysostom writes:

If any persons had removed the body, would they before doing so have stripped it; or if any had stolen it, would they have taken the trouble to remove the napkin, and roll it up, and lay it in a place by itself; but how? They would have taken the body as it was. On this account John tells us by anticipation that it was buried with much myrrh, which glues linen to the body not less firmly than lead; in order that when you hear that the napkins lay apart, you may not endure those who say that He was stolen. For a thief would not have been so foolish as to spend so much trouble on a superfluous matter. For why should he undo the clothes? And how could he have escaped detection if he had done so? Since he would probably have spent much time in so doing, and be found out by delaying and loitering. But why do the clothes lie apart, while the napkin was wrapped together by itself? That you may learn that it was not the action of men in confusion or haste, the placing some in one place, some in another, and the wrapping them together (Homily 85 on the Gospel of John, 4).

I had no idea that myrrh “glues linen to the body not less firmly than lead.” Thank you to Chrysostom for pointing that out. Chrysostom indentifies that the care taken not just to unwrap the body but also lay the head covering (“napkin”) aside separately means that something altogether different happened. Something deliberate, something careful, something unafraid. Yet something that is still hidden from them.

Which makes me wonder what is meant when John says of himself, “he saw and believed,” when he follows it with “For they did not yet understand the Scripture that he had to rise from the dead.” I think that John and Peter have the seeds of hope when they encounter the empty tomb in the state it is in. They believe in the possibility of all the hints that Christ gave them about them seeing Him again after He dies. They have yet to meet Him in His Resurrected Body. The angels have yet to explain to Mary what happened. This is the moment of hope! Humanity sees order, care, and absence where there should be death. What a mysterious but wonderful sight. Mourning is no longer appropriate, but instead hope — maybe, just maybe, all those incredible things Jesus told us are true!

The empty tomb is the picture of our new reality: the place of death has been ransacked and re-ordered. Mysterious hope fills us but God remains out of sight; we must trust the Lord’s Word and grow together as a Church in the sacraments He has given us until we meet Him face-to-face.

Even in the decades after His Resurrection, St. Paul in today’s second reading writes of a “hiddenness” that characterizes Christianity: “For you have died, and your life is hidden with Christ in God. When Christ your life appears, then you too will appear with him in glory.” This is the wonderful mystery we are able to live to this very day. People bemoan this state, they want proof that God exists, but what we are given is the empty tomb. This is, in fact, proof, albeit proof of a different type. We have to remember that God fundamentally wants us to yearn for Him, to thirst for Him, to live in a differently ordered way that shows how central He is to us despite His hiddenness. He has given us free will, but “to whom much is given, much will be required” (Lk 12:48). We are called to use our free will to choose His will precisely because He gave us the empty tomb, His ordered absence that speaks volumes.

Of course, much more is given to us. He will appear to his disciples and His Spirit explodes into the world in all its fullness, working amidst humanity constantly and to this day. All of this is most evident in the liturgy, in the sacraments.

But for now, let us consider the empty tomb, the mystery of His disappearance from the grip of death. It is the surest sign we require.