Tuesday, 7th Week of Ordinary Time: James 4:1-10 and Mark 9:30-37.

What a nice connection between the two readings today. James asks in his letter “where do the conflicts among you come from?” and likewise we hear Jesus ask “What were you arguing about on the way?” The answer in both cases is our lack of humility before God.

First, let’s consider the Letter of Saint James. He puts the blame for our sorry state of affairs — that is, war, conflict, covetousness — squarely on our unbridled passions. We’ve all seen people with uncontrolled passions: drink until drunk beyond belief, eat until overfull, sex with whomever and whenever, power at the cost of our morality or basic humanity. Heck, we might be those very people at times. St. James tells us there are grave consequences here: “Do you not know that to be a lover of the world means enmity with God?” Even more forcefully: “whoever wants to be a lover of the world makes himself an enemy of God.” God wants us to be with Him in perfection and glory, and we betray his desire for us when we desire the world more than Him.

Jesus and the apostles were clear on this point. Epistles from St. John, St. Paul, and St. Peter all have a version of “Do not love the world or the things in the world” (1 Jn 2:15) or “Do not be conformed to this world” (Rom 12:2). Just before his arrest and Passion, Jesus prayed on behalf of his disciples to the Father: “I have given them your word, and the world has hated them because they do not belong to the world, just as I do not belong to the world. I am not asking you to take them out of the world, but I ask you to protect them from the evil one” (Jn 17:14-15). So there it is: we Christians do not belong to the world, we must tame our passions and ask for God’s protection from Satan.

Why, then, after 2000 years of hearing this message, do we still cling to this world and its passions, knowing that it’s an affront to our new state of grace won by Christ? As our small morning mass congregation was reminded today by Fr. Erik Richtsteig, it all stems from The Fall of Adam and Eve, when our human desires and intellect became warped and out of sync with God. This is our human condition. How, then, do we return to God from our fallen state?

St. James quotes scripture: “God resists the proud, but gives grace to the humble.” His instruction for us is to “submit yourselves to God … Humble yourselves before the Lord and he will exalt you.” Ah, yes, that frighteningly difficult virtue of humility. While I’m not very good at being truly humble, I do appreciate the way St. James tells us that the act of humility here is submission to God. It’s not a submission to other people, a type of meekness in the face of others. This I can begin to do. In my mind, it’s much easier to humble myself before the awesome wonder of the Creator of the Universe than a self-righteous co-worker arguing with me. (The harder part is seeing our Lord in that co-worker, and loving that person because the Lord resides in her, too.)

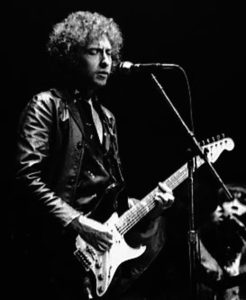

St. James’s dialectic of world/God reminds me of the words of our reluctant Nobel Laureate and national folk-rock treasure, Bob Dylan: “Well, it may be the devil or it may be the Lord, but you’re gonna have to serve somebody.” If Bob is right (and St. James), then we are fooling ourselves if we believe that following our self-interest is somehow our most “free” state of being. Following our passions is just being a slave to the world (whose prince is Satan, as we are told). We’re literally serving something/someone who has no care for our salvation, someone who deviously makes us think we’re serving ourselves in the process. Wouldn’t it be better to serve God, who yearns to give us eternal salvation?

Fr. Erik deftly reminded us that this is a great reading to have the day before Lent starts. Taming the passions through fasting and giving up things during Lent “exercises our spiritual muscles,” in his words. These things serve a real purpose (aside from what looks like sadistic torment to non-Catholics) — they bring us closer to God by helping us detach from the world and our passions. Fasting and little deprivations help us prepare for bigger temptations and challenges that come our way. The saints’ lives are a grand tapestry of testimonials to this effect. Bring on Lent!

This brings us to the gospel reading from St. Mark, where Jesus finally opens up to his disciples and tells them that he will “be handed over to men and they will kill him, and three days after his death he will rise.” In hindsight, we can grasp the immensity of these prophetic words, that they are in fact the inauguration of the New Covenant and our saving grace, but the disciples did not understand and “were afraid to question him.”

St. Mark, in all his brevity being the shortest of the gospels, is a master at pointing out the awkward failings of humans. When Jesus asks what they were arguing about along the way, Mark states in the dry cunning befitting a police procedural: “But they remained silent. For they had been discussing among themselves on the way who was the greatest.” It’s easy to imagine the embarrassment of being called out for such hubris. Maybe some flushed cheeks while they stare at their sandals, shifting uneasily on the ground as they stand there in ashamed silence. Awwwwkward.

Jesus (we must wonder if he suppresses a big sigh at this point) simply sits down, calls the Twelve to him and explains that “If anyone wishes to be first, he shall be the last of all and the servant of all.” This only makes sense if we understand that “being first” is not measured in this world, by people in this world, but by God, in His Kingdom. This is the type of teaching echoed in St. Paul’s “Do not be conformed to this world.”

Jesus follows this up with the gentle gesture of putting his arms around a child in their midst and saying “Whoever receives one child such as this in my name, receives me.” Several things are happening here. First, if important men such as chosen apostles spend their time receiving a child into their arms, they are performing an act of humility. This is the first level of meaning. Second, Jesus constructs an analogy between himself and the child — by acting as he acts, they receive him. He is the child, not just figuratively, but literally, the Son of God. And this sonship is an important perspective: the good son is wholly prefigured by and attentive to his father. Being humble like a good son is humble before his father is the entire message here, and the apostles will be able to receive that type of humility by following Christ’s example, yes, but also because of the mystical nature of this Christ, this God-become-man. Thus, the second part of his statement, “and whoever receives me, receives not me but the One who sent me.” This is the nature of our salvation as adopted sons and daughters of God through Christ. He opens the doorway of true filiation with God. He is the example, but more importantly, both the herald and the very means of salvation. His saving Passion and Resurrection, which he was just trying to share with them, is the event that will enable them (and us) to not be slaves to our passions but receive divinification when we are humble before God.

Whoever is skeptical about the Word of God, about Christ, needs to just read and understand the import of passages like this in St. Mark to realize that this isn’t something a writer can just “make up.” This revelation of the Lord’s presence, ways, and plan for us is something so densely a part of Christ and his dealings with his disciples that every gesture and word recorded resounds down the centuries. St. Mark admits that the disciples didn’t understand what Christ was talking about, and it’s possible that St. Mark himself didn’t realize the full import of the events and words that he faithfully wrote down for us. This is the revelation of God, and as important today as it ever was.