Feast of the Transfiguration of the Lord. Daniel 7:9-10, 13-14, 2 Peter 1:16-19, Luke 9:28b-36.

Rejoice! Today we commemorate and celebrate the gratuitous love of the Father to bolster the faith of Peter, James and John by allowing them to witness a vision of Jesus in his glory. This episode in the life of Jesus and the Apostles is so rich and full of meaning for the Church. On Sunday, I led a discussion with our Lay Dominicans and inquirers about the Transfiguration in anticipation of this feast day. We discussed St. Thomas Aquinas’s writing about the fittingness of the Transfiguration as presented in the Summa Theologica, Part III, question 45, and I’d love to share a few bits of that fruitful discussion here.

Fittingness Versus Necessity

One of the questions an inquirer asked during our discussion was, “If the Transfiguration never happened, would the Crucifixion and Resurrection still have happened? In other words, was it necessary to our salvation?” This question is actually at the heart of how St. Thomas presents many aspects of salvation history. He readily admits that God could have ordered things differently — even to the point of not having the Incarnation or the Passion. These things, according to St. Thomas (and St. Athanasius and St. Anselm before him), are not “necessary,” per se, but he shows how they are “fitting.” The Latin word he uses is Convenientia, which translates to suitable, appropriate, harmonious or beautiful. The Church Fathers had a very good reason to be thinking in this way. First of all, they knew that they could never fathom the mind of God and “prove” some sort of necessity around the events and stories of our salvation history. Second, they had a huge body of texts that emerged from the early years of the faith, some orthodox and true, and some that were not. This contemplation of convenientia was a critical tool in helping to decide what writings were part of the canon of the New Testament.

As that same inquirer pointed out during our discussion, a good example of something that was NOT fitting would be in the apocryphal Infancy Gospel of Thomas, when Jesus is said to curse and kill a child who bumped into him. This is not consistent or harmonious with what we know of God and of Jesus’ ministry on Earth.

But beyond a tool for determining the truth of early texts, I think contemplating fittingness is a fantastic perspective for any kind of lectio divina. With this starting point, we can ask questions about why events happened and have them always point back to God and how he is revealing himself to us (as opposed to treating the divine plan like a puzzle to be solved, as if we could ever comprehend it fully!). In the case of the Transfiguration, the “why” of the event is answered amply by many Church Fathers. Here’s what St. Thomas has to say: “For anyone to walk straight along a road, he must have some knowledge of the end … Above all, this is necessary when the road is hard and rough, the going is heavy, but the end is delightful … Therefore, it was fitting that He should show His disciples the glory of His clarity (which is to be transfigured), to which He will configure those who are His.” In other words, one reason the Transfiguration happened was to provide the Apostles with the backbone to persevere when the going got tough — to let them see the goal of divinization alongside Jesus. Understood as a completely unnecessary but helpful and beautiful blessing for the Apostles (and the Church as a whole), we can start to glimpse the overwhelming, overabundant love the Father has for us, his delight in showing us a Way to him through his Son.

Bright Clothing

Another aspect we discussed was that more than Jesus’s face was transfigured: “his clothing became dazzling white.” This might seem like a simple detail, but the Church Fathers fastened onto it with gusto. The first reading from the Book of Daniel gives us a clue as to why they might have done so: “The Ancient One took his throne. His clothing was bright as snow … Thousands upon thousands were ministering to him, and myriads upon myriads attended him.” So bright white clothing seems to be an important detail in this beatific vision, but what does it mean?

St. Thomas tells us that “the clarity which was in His garments signified the future clarity of the saints.” This might seem like a leap, but he traces it back to St. Gregory the Great, who wrote, “because in the height of heavenly clarity all the saints will cling to Him in the refulgence of righteousness. For His garments signify the righteous, because He will unite them to Himself.” As we think of garments as things that cling to and adorn a person, this parallel starts to make more sense. The saints cling to Christ and his Way, and by so doing, they fulfill the word of God given to Isaiah: “You shall put all of them on like an ornament” (Isaiah 49:18). Thus, the Transfiguration is truly the full beatific vision: Christ in his glory, surrounded by the law (Moses) and the prophets (Elijah) and all the saints (his bright clothing, adorning him). What is nice about this understanding is that we see glory going back to God rather than ourselves in this vision of heaven. It’s not about us gaining virtue and being so good that we are given the gold star of heaven. It’s about us loving God so much (as close as we can mirroring the love he first gives to us) that we adore and adorn him, becoming more and more like Christ as an acknowledgement of the plan the Father has for all of us. Imitation is the sincerest form of flattery, so the saying goes, and we can see a small truth — yes, we are trying to imitate Christ, but even more than trying to flatter him we are trying to sincerely love him and show the world that he is the only Way to heaven. Let us be your brilliant clothes, nothing more, O Lord!

We also discussed how there is more support for this understanding of the bright clothing in the Book of Revelation according to St. John: “Then one of the elders addressed me, saying, ‘Who are these, robed in white, and where have they come from? … These are they who have come out of the great ordeal; they have washed their robes and made them white in the blood of the Lamb.'” So John was doubly gifted with the vision of the Transfiguration during Jesus’s lifetime and then again in the visions that became the Book of Revelation. Only this time, the white robes have received their color from walking the Way of Christ — from going through “the great ordeal” and washing them in “the blood of the Lamb.” Whether adorning Christ or more literally being worn by the saints in heaven, the brilliant white clothes seem to symbolize the members of the Church who have remained faithful to the Way and entered into the divine heavenly eternity.

There is one last interesting note we discussed about the clothing. One of the great early Church Fathers was Origen, who lived in the first half of the 200s AD. His influence was huge. Many later Church Fathers quote Origen when discussing the Transfiguration and many other mysteries of the faith. He writes that the white garments are “the words in the Apostles which indicate the truths concerning Him,” that is, the Gospels themselves. Origen adds that if someone speaks with deep theology of Christ and explains the Gospels brilliantly, “do not hesitate to say that to Him the garments of Jesus have become white as the light.” Imagine saying that the next time you hear a good homily! “Hey, Father, the garments of Jesus really became white as the light today! Thanks!”

Moses, Elijah, and Unfinished Stories

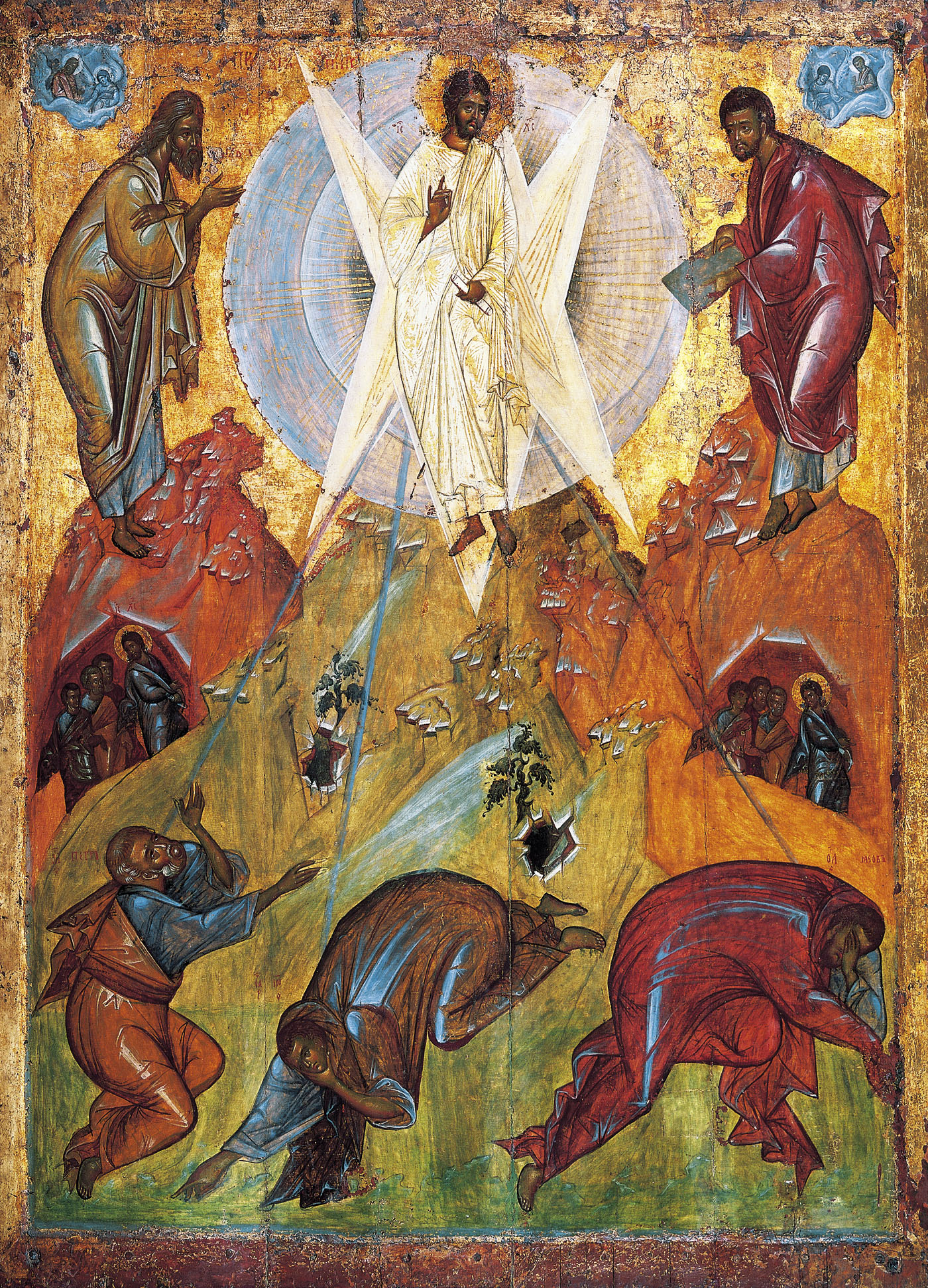

Of course, the other important detail, as we see in each of the paintings on this page, is that Moses and Elijah were present during the Transfiguration. Our little discussion group talked about how this might be fitting. First, we read the six separate ways that St. Thomas points out the significance of these two towering Old Testament figures. The one most often mentioned St. Thomas attributes to St. Hilary of Poitiers: that Moses symbolizes the law and Elijah the prophets, and this reminds everyone that Christ was foretold by these two important men.

But then one of our life-professed Lay Dominicans made an observation that none of us had considered before: “Isn’t this the first time Moses appears in the Holy Land?” We all went silent, and then burst out with agreement. Even Fr. Gabriel admitted that he had never read any commentaries that bring up this important detail.

Next, we had to contemplate how this might be fitting and why it might be important. We noted that both Moses and Elijah leave scripture with their stories somewhat unfinished or at least a little unsatisfying to the listener. Moses is told by God that he can’t enter into the Promised Land because the generation he ushered through the wilderness was so ungrateful and rebellious. So, he dies just outside of the Promised Land. In a way, he must suffer and sacrifice for the sins of others (sound familiar? nice foreshadowing of Christ). Elijah, on the other hand, is taken up to heaven alive. Why? What is he doing there? He’s not the Messiah, even if he is one of the greatest prophets.

Both of these stories find a suitable and fulfilling ending here in the Transfiguration, however. Moses does get to enter the Promised Land, but only now and here, with Jesus Christ as the Savior who ushers in the Kingdom. God is not a vengeful God but a loving God whose plan spans all time and who loves us so much that he instructs and points the way through generations upon generations. He wants Moses with him — Moses the bearer of his law who now comes back to the bosom of the Father in the presence of the fulfillment of that law.

Why Elijah is still alive, keeping the Jews in a state of suspense about his possible return, becomes clear when he returns here to commune with and point to Jesus Christ. Elijah, speaker of God’s living Word, never dies as the bearer of that living Word, and only reappears alongside that living Word made flesh. Jesus, who unites the dead (Moses) and eternal life (Elijah), is in the center of this vision. Jesus is the true Alpha and Omega here.

Like the brilliant clothes, Moses and Elijah are not there for their own glory, but to adorn and ornament Jesus Christ, the Son with whom the Father is well pleased. The Father’s voice and the Holy Spirit in the form of a cloud (something seen because it obscures the sun and darkens the sky and yet somehow “a bright cloud overshadowed them” in Matthew’s account) also appear, but again, to point to the Son. If ever there was an argument for the divinity of Jesus Christ, this is it!

I hope this post did some justice to sharing the fruits of a lively discussion and I also hope it enkindles a newfound reverence for the wonder of the Transfiguration. Thank you, God, for this vision of heaven, given to sustain us in our belief, faith, and fidelity to your Word.