Monday of the Fifth Week of Lent: Daniel 13:1-9, 15-17, 19-30, 33-62, John 8:1-11.

Wow, what a first reading today – 1,079 words! I’m guessing, but I think it’s the longest one outside of Easter Vigil. Thankfully, it reads like the script for a telenovela, so there’s a certain pacing and several plot twists to keep us interested. This reading and the gospel seem to be about adultery — at least the accusation of adultery. But in the end, they are more about lust, the perversion of God’s law, and divine justice. Let’s dig in.

Susanna, the heroine of the first reading and my wife’s namesake, is a fitting object of desire: “a very beautiful and God-fearing woman.” This reading is ostensibly about her, but really it’s about the two elder judges, complete degenerates that they are. When they begin to lust after her, the state of their sin is described in these terms: “They suppressed their consciences; they would not allow their eyes to look to heaven, and did not keep in mind just judgments.” This strikes me as being so on-point. Unbridled lust is absolutely a suppression of our God-given conscience, something that we have to cultivate and listen to in order to live upright lives. Lust is also a determined effort not to look at God, for who can contemplate the face of God and still be drawn to evil? They also are determined not to think of “just judgements” — ironic for judges and a choice that will come back to bite them. This description cuts right to the spiritual truth of their actions. When we think of being caught up in lust, this series of choices made on the spiritual plane might not occur to us because physical desire can be so blinding of a force (at least in my experience as a man), almost like animal instinct. We’ve all heard of or experienced sex as a result of being “caught up in the moment.” To me, at least, lust doesn’t seem as calculated or deliberate as it is described, but when I think about it, this is exactly what’s going on in terms of my spiritual being. Lust has an amazing ability to cause a huge discrepancy between what we experience mentally and physically and what we experience spiritually.

All religious orders must address lust as communities of same-sex people living out their lives in sexual abstinence. Our saints from religious orders have gone to great lengths to preserve their purity. St. Josemaria Escriva said: “To defend his purity, St. Francis of Assisi rolled in the snow, St. Benedict threw himself into a thorn bush, St. Bernard plunged into an icy pond…You…what have you done?” Now that speaks to the power of temptation and lust! Yes, there’s something special about this sin, as St. Alphonsus Liguori writes, “In temptations against chastity, the spiritual masters advise us, not so much to contend with the bad thought, as to turn the mind to some spiritual, or, at least, indifferent object. It is useful to combat other bad thoughts face to face, but not thoughts of impurity.” How interesting, and consistent with the description of how the judges were affected in today’s first reading. If turning your thoughts to a spiritual matter is the best way to combat lust, then the description of how they “would not allow their eyes to look to heaven” is telling indeed. In addition, the line about how they suppressed their consciences is exactly the opposite of what Pope Saint John Paul II writes about how to deal with lust: “Deep within yourself, listen to your conscience, which calls you to be pure…a home is not warmed by the fire of pleasure, which burns quickly like a pile of withered grass. Passing encounters are only a caricature of love; they injure hearts and mock God’s plan.” I bring up all of these saints not just to complement the description of the sin in the first reading, but to help us remember that even though the sin appears to be purely physical, it is in fact a deep spiritual injury to ourselves and God.

Lust as temptation is dangerous because it perverts our spiritual nature, turning us into baser animal creatures. If unchecked, it culminates in lust as an action. Today, we hear the two elder judges tell Susanna, “give in to our desire, and lie with us. If you refuse, we will testify against you.” Their spiritual natures are so undermined and perverted that they threaten rape and end up carrying out false testimony when she screams for help. Shortly after this, we hear the cringe-worthy, sleazy details of their false testimony. How interesting that the train wreck of sins is so caught up in power and wielding power on this earth. It is no mere coincidence that these men are elder judges. They represent the corrupting influence of the world, the depravity that reigns in the place where justice should be. As a sharp contrast, a young Daniel (think: new life in the spirit) intervenes to help restore a community twisted by sin: “God stirred up the holy spirit of a young boy named Daniel, and he cried aloud: ‘… Are you such fools, O children of Israel! To condemn a woman of Israel without examination and without clear evidence? Return to court, for they have testified falsely against her.'” Here we have God’s intervention because grave sin and injustice are at stake. The reading hinges on this moment, when God works through his chosen prophet Daniel to confront the people with truth. Like an early version of a detective crime story, Daniel smoothly trips up the elders to reveal their treachery. Finally, unlike what we hear in the gospel, divine justice is enacted on the spot.

I think this is more than a critique of Jewish law and earthly justice systems. Likewise, I think it’s more than a simple morality fable even though the narrative structure reads like it. Remember that we are told that there was a prophecy about these judges: “of whom the Lord said, ‘Wickedness has come out of Babylon: from the elders who were to govern the people as judges.'” This brings the scope of salvation history into play. God has announced their coming, and as we see with other prophesied events, their arrival is a moment for God to reveal something about His desire to have us come to Him in the Kingdom. It’s more than just a story of right vs. wrong. We learn two things in this vein:

- God hears us when we are pure of heart and call out to Him. Susanna precipitates David’s prophetic intervention when she cries, “O eternal God, you know what is hidden and are aware of all things before they come to be: you know that they have testified falsely against me.” Then we are told, “The Lord heard her prayer.”

- God promises divine justice, especially when earthly justice falls short due to human guile. Daniel does not promise a lynch mob or a simple execution; instead, he speaks of justice delivered by spiritual beings: “the angel of God waits with a sword to cut you in two so as to make an end of you both.” And even though the people do take the judges’ lives, Daniel’s words speak to a much more profound justice. God, through this scripture, gives us a vision of the Kingdom, where purity and virtue live with Him and where sin and perversion of the spirit are eradicated.

Let’s turn to the gospel, where Jesus Christ is the true way we will be re-configured in the Spirit. Daniel’s life and works simply pointed to Christ, like an early promise of the configuring and justice yet to be fully unveiled. And Jesus, as ever, surprises us with a teaching about God’s law and justice.

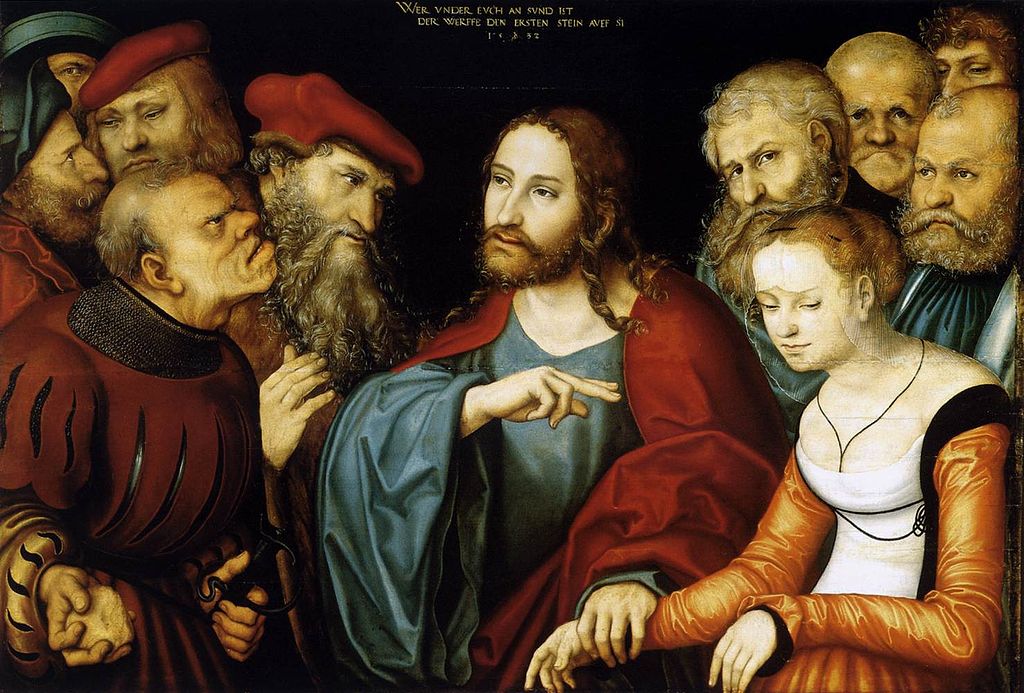

When the scribes and Pharisees throw a woman into the middle of the place where Jesus is teaching, St. John tells us that their question to Jesus about punishing her adultery was “to test him, so that they could have some charge to bring against him.” How like the elder judges in the Book of Daniel! They are here on false pretenses, not interested in justice but instead their own gain. Like the elder judges, they have bound themselves to the quest for worldly power and control; in so doing, they are avoiding looking at God. They lust not for sexual relations but for power, specifically the power of the judge to charge and condemn Jesus.

The other important thing here is the way the narrative of adultery is dealt with. On the surface, this episode seems to be a slam-dunk according to Jewish law, and when Jesus allows the woman to go unpunished, it seems to subvert that law. But John’s statement about their hidden intentions changes the narrative completely. They are not seeking to identify sin at all. Christ knows what is in their hearts, and for Him this encounter is about their own falseness, not about the woman. After all, isn’t this what all encounters with God are about? When we stand before God, it is a personal encounter — we don’t go with a list of people we want to praise or condemn. Our role as His creation, His servants, is not one where we play judge or colleague.

So as the sun of righteousness turns His gaze on the scribes and Pharisees, let’s remember that He understands their priestly role as upholder’s of God’s commandments and precepts. In fact, He shows them that their sin is the betrayal of the solemn, pure role they are supposed to play for their community.

St. Augustine of Hippo explains the ironic position that these false upholders of the law occupy: “You have heard, O Jews, you have heard, O Pharisees, you have heard, O teachers of the law, the guardian of the law, but have not yet understood Him as the Lawgiver. What else does He signify to you when He writes with His finger on the ground? For the law was written with the finger of God; but written on stone because of the hard-hearted. The Lord now wrote on the ground, because He was seeking fruit” (Tractate 33 on the Gospel of John, 5). Thank you, St. Augustine, for connecting that mysterious detail from today’s gospel to the writing of the law. Many people wonder what Jesus may have been writing on the ground. The simple act of doing so in response to the question He was asked almost seems like an evasion or an act of rudely ignoring them. But not so! You see, these are professionals of the law, brought together in their common purpose of tripping up Jesus, not by some coincidental experience of all seeing a woman commit adultery at the same time. In other words, although they claim that she was “caught in the act,” they are not themselves the witnesses. This is a form of false witness in itself.

For accusations of adultery without witnesses, the Torah describes a water trial (called Sotah) that the woman must undergo. As part of this, “the priest shall put [the charges and penalties] in writing, and wash them off into the water of bitterness” (Numbers 5:23). Here we have the incarnate Word of God, the One who forms the Torah and its prescriptions around how to carry out justice, bending down to enact the prescriptions of the law in front of the scribes and Pharisees. He is reminding them that there is a form of earthly justice that was handed to them by God and which is a solemn gift not to be tampered with. He knows that these prescriptions are in place so that there is no miscarriage of justice. He lifts up the law to fulfill the spiritual work it is intended to do: to keep our hearts clean from lies and sin, to keep sinners from perverting the justice God intends in the world.

So when He stands back up at their insistence and says, “Let the one among you who is without sin be the first to throw a stone at her,” we understand that this is a specific accusation against them. He knows their hearts and they have been called out. In response, “they went away one by one, beginning with the elders.” The elders, the ones who should know better than the rest, but in whom lies the entropy of sin. They slink off first, avoiding the embarrassment of those left later.

Then they are left alone. Jesus’s simple questioning is a reminder of how we must all encounter God: “Woman, where are they? Has no one condemned you?” We must all account for our sins in honesty before God, no one else will be there to condemn or defend us. He knows our hearts and our deeds. But then we have this pestering problem of Him letting a woman “caught in the act” of adultery leave unpunished. What is the point of this episode? That no matter what you do, all will be forgiven?

I don’t think so. Jesus is incarnated to give us a new way, a new unity with God, not to judge and destroy. His mission is about fidelity of Spirit. If He has anything new to say about adultery, it is to point out that the worst adultery is to break our most fundamental covenant and union with God. This spiritual adultery is what the scribes and Pharisees just committed, not the woman.

Nothing about this final exchange is like the other miracles or healings he accomplishes. He does not ask her about her faith or belief. He does not establish the atonement and request for mercy that is the requirement for spiritual healing. We must conclude that this encounter is not about sin being forgiven. Not her sin, certainly, because He doesn’t ritually absolve her. Instead, He renews God’s call to be holy: “Go, and from now on do not sin any more.” It’s not that He didn’t know if she committed adultery and was unwilling to point it out. After all, He told the Samaritan woman at the well that she had 5 husbands and was living in adultery at that moment. No, the lesson of today’s gospel is not so much about forgiveness as it is about the ultimate sanctity of our spiritual fidelity with God.