Twenty-Third Sunday in Ordinary Time: Wisdom 9:13-18b, Philemon 9-10, 12-17, Luke 14:25-33

This Sunday, we listened to a fantastic set of readings, including an echo of the gospel reading from St. Luke we heard three Sundays ago: “Do you think that I have come to establish peace on the earth? No, I tell you, but rather division. From now on a household of five will be divided …” (Luke 12:51-52). In this Sunday’s gospel, Jesus proclaims to his followers, “If anyone comes to me without hating his father and mother, wife and children, brothers and sisters, and even his own life, he cannot be my disciple.” How do we react to these words? Is our reaction warranted?

We are traveling currently, leaving Salt Lake City after 25 years and starting our retirement with a “Farewell USA tour” to say goodbye to friends and family around the country (and see many roads we haven’t before we move to Spain permanently). It was a little hard to condense everything we owned into our SUV, but the process of giving away most of our belongings to friends and charities was actually quite freeing. For the next three months, our routine includes leveling the car on a camping spot so that our sleep in the rooftop tent doesn’t end up with us rolling into a clump on one side of the tent. Our dog is with us, until we leave him with Suzanne’s sister in Oregon in October, and we’re having fun on hikes and in lakes.

As a result of being nomads, we are getting to experience Mass in Catholic churches around the West. We went to St. John Neumann parish in North Las Vegas three weeks ago, St. Sebastian Church in Santa Paula, CA, two weeks ago, St. Francis of Assisi in Palm Desert, CA, last week and St. Daniel’s Catholic Church in Ouray, CO this Sunday. I’m thinking of writing a blog in a few months just about these experiences as a sort of random survey of the state of affairs of Catholic liturgies in the US, but I’ll leave that to another day. But one thing I heard three Sundays ago in Las Vegas and again in Ouray was that these gospel readings are “hard.” You may have heard something similar at your local church.

In fact, the deacon who gave the homily this Sunday in Ouray really pushed on the point. “Did we just hear Jesus tell us that we have to hate our parents, our wives and our siblings?” he asked incredulously. “How can we reconcile this with our Lord, who we know to be all-forgiving and all-loving?”

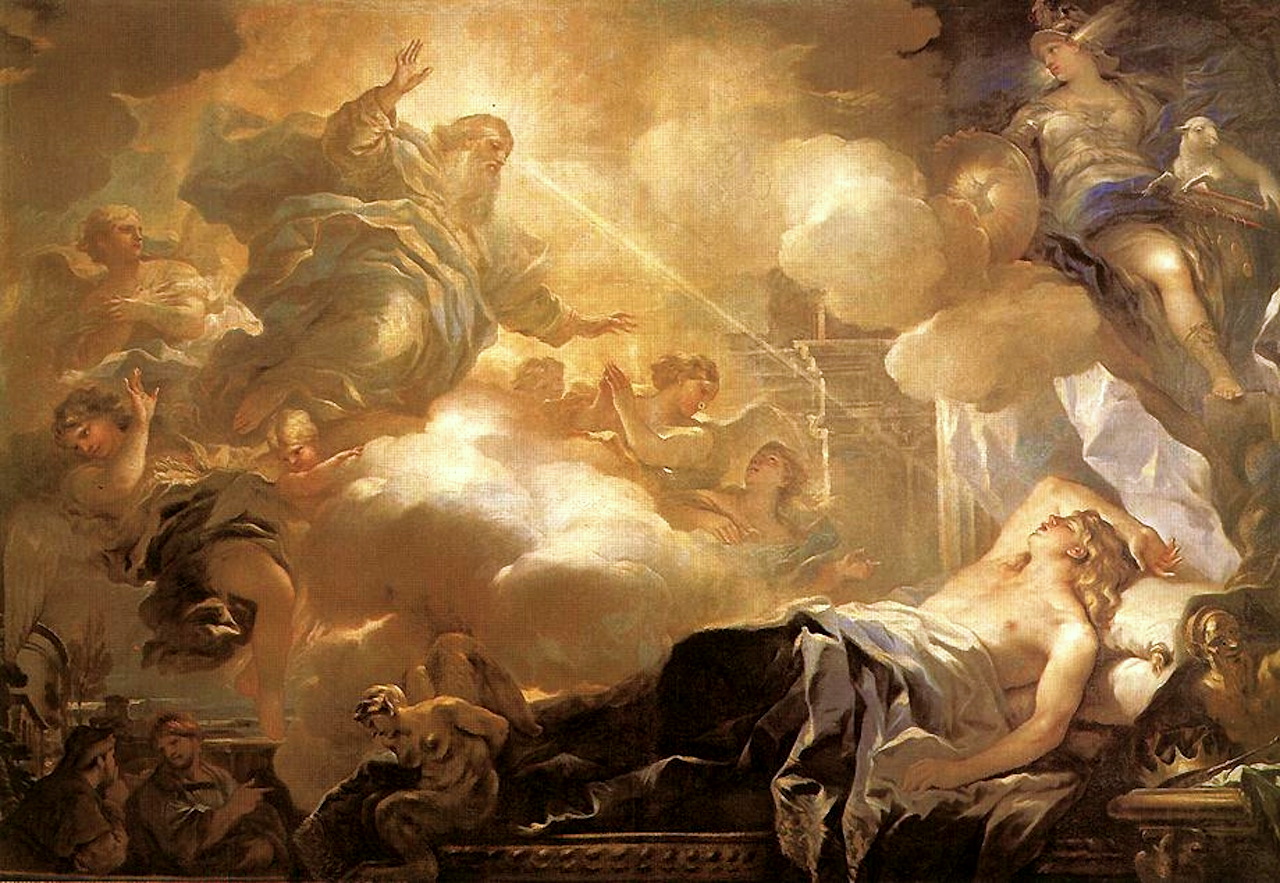

This is an incredibly important question for modern Catholics, and I think the answer is right in front of us, in the opening of the first reading from the Book of Wisdom: “Who can know God’s counsel, or who can conceive what the LORD intends? For the deliberations of mortals are timid, and unsure are our plans.” So that I’m not just answering a question with another question, I hope to elaborate what I think the Word of God this Sunday presents to us.

The deacon at our church gave a thoughtful homily, first tracing the fact that “hate” in Hebrew more often meant “to love less.” I’m going to take a moment to both agree with him and add a little nuance. From my research, I’ve found that it’s true that in most contexts, שׁנה (sana’) in Hebrew does not translate directly to our everyday use of the term “hate.” The main difference is that, in modern English, hate is most often associated with emotions. For example, “I hate you,” is one of the worst things a teenager can say to a parent, often in a fit of pique. “I hate cilantro” is less emotionally charged, but still carries the feeling of disgust. In ancient Hebrew, especially in a scriptural context, the word hate (sana’) is most often used in reference to God. Consider Psalm 139:

Do I not hate those who hate you, O Lord?

And do I not loathe those who rise up against you?

I hate them with complete hatred;

I count them my enemies.

I’ve read that some Jewish scholars prefer to use “reject” here rather than “hate.” The clear overtone is one of judgment and moral rejection, not something said emotionally or in a fit of anger. We should remember this when we read the Old Testament. When we hear at the beginning of the Book of the Prophet Malachi, for example, that God says, “Yet I have loved Jacob but Esau I have hated,” we can understand that he has rejected Esau from his favor.

So, at least in the Jewish scriptural context, “hate” is not normally the emotionally charged verb it is in English. But I think the deacon was a little short of the target when he said it was “love a little less,” because there is definitely a sense of judgment (especially when applied to God) and moral decision-making. Technically, I guess that judging against something makes it “less” than the thing it is compared to, but why are we softening the impact here? I think that modern ears need to hear something like this because it helps us “reconcile” this with our vision of the Lord being all-loving.

But this is crucial! What does it mean to “reconcile” these thoughts? This means that we have preconceived notions of what love is, what forgiveness is, and we’re putting Christ’s words up against these notions, trying to look for some way they cannot contradict each other. Stop! We should recognize from the beginning that a.) do not put the Lord your God to the test, and b.) faith demands an acceptance of that which we cannot fathom or immediately understand. So, let’s meet Christ’s words with awe and reverence and try to accept and ponder them before we have some kind of emotional reaction.

The Church, in her wisdom, prepares us for this gospel reading through the inclusion of the first reading. Again, it starts, “Who can know God’s counsel, or who can conceive what the LORD intends? For the deliberations of mortals are timid, and unsure are our plans.” In other words, know your shortcomings! Our thoughts are “timid” — too small to approach the grand thoughts of the divine — and this should make us humble as we approach the Word of God. The second part of this reading brings in a corollary important to understanding the gospel reading: “For the corruptible body burdens the soul and the earthen shelter weighs down the mind that has many concerns.” So, not only should we not attempt to fathom God’s plan and Word without the grace he provides for us, but we should recognize that we are already handicapped in understanding spiritual matters, for the “body burdens the soul” and “the earthen shelter weighs down the mind.” Jesus will return to this theme of earthly matters being problematic to us achieving the Kingdom. To recap, in a few sentences, the first reading reminds us that not only are we unable to fathom the plans of the divine mind, we are further encumbered when we try to think on spiritual things because we are concerned with earthly things.

As if this dose of humility isn’t enough, the author of the Book of Wisdom continues: “And scarce do we guess the things on earth, and what is within our grasp we find with difficulty.” Ha! How true. Even figuring out earthly things like, “what career should I choose?” or “does she love me?” or “how can we organize a society without fighting with each other?” are found with difficulty, if at all. The answer to this big multivitamin of humility is given at the end of the reading: “Or who ever knew your counsel, except you had given wisdom and sent your holy spirit from on high? And thus were the paths of those on earth made straight.” GRACE through the Holy Spirit is the only way we can make sense of ourselves and our world, much less the spiritual paths set before us by God. This important reading should set us straight in meekness and humbleness before we approach the Gospel — not in a stance of comparing Jesus’s words against our timid earthly notions of love and hate.

So, when Jesus says, “If anyone comes to me without hating his father and mother, wife and children, brothers and sisters, and even his own life, he cannot be my disciple,” if we listen to this alongside everything Jesus has taught and shown us, we can grasp his meaning with the help of his Holy Spirit. If we think of the word hate as “reject,” we recognize that Jesus has said something similar many other times:

- “So therefore, any one of you who does not renounce all that he has cannot be my disciple.” (Luke 14:33)

- “No one who puts his hand to the plow and looks back is fit for the kingdom of God.” (Luke 9:62)

- “And everyone who has left houses or brothers or sisters or father or mother or children or lands, for my name’s sake, will receive a hundredfold and will inherit eternal life.” (Matthew 19:29)

But today’s words seem like more than other statements about worldly renunciation. He’s talking about our most cherished relationships here on earth. If this sounds extreme, well, yes — I think it is. It’s impossible to hear Jesus in the gospels without hearing this type of “all-or-nothing” message. He tells the would-be-follower who wants to bury his father, “Leave the dead to bury their own dead. But as for you, go and proclaim the kingdom of God” (Luke 9:60). !!! I mean, that’s pretty extreme. We think of funerals as a respectful, God-forward practice, but in the face of God Himself, this ritual pales in comparison. Without a doubt, this Sunday’s gospel challenges us to be “all-in” in regards to following Jesus.

Jesus follows up this sentence with words of preparation: “Whoever does not carry his own cross and come after me cannot be my disciple.” With how often-referenced this sentence is, we can lose track of its power. The cross is sacrifice, undoubtedly, but it to his listeners, it was likely more charged with the understanding of spectacle and shame. After all, it wasn’t until his Resurrection that the shame and spectacle of the Cross turned into the glory of sacrifice.

Jesus is preparing his listeners to be true followers. He is letting them know that those closest to them will likely disagree with their newfound faith in Jesus Christ. He is presenting them with the fact that they must hate/reject those closest to them when they cast suspicion and begin to shame these new Christians and even make a spectacle of them. Jesus is both preparing them and trying to give them courage. This is why the end of the gospel reading focuses on “calculating the cost” of discipleship. Jesus wants his listeners to know the cost, to brace themselves and find the courage to follow him.

When is the last time we felt that we were carrying shame or spectacle by following Christ? Not that we should seek these things out, but I think we perhaps instinctively shy away from these, as anyone would. But this gospel is for us as much as it is for first-century Jews. When is the last time you boldly made the sign of the cross and said a prayer before your meal in a restaurant? This small gesture of thanks to God is essential with everything we do, but most often we don’t want to draw attention to ourselves in public. Are you picking up your cross here or just leaving it on the ground? When is the last time you walked in a Eucharistic procession in your town? I can recall a number of them on the University of Utah campus, including the catcalls and obscenities occasionally yelled at us. Atheistic culture wants to make Catholics feel ashamed, out-of-date, and ridiculous for something as beautiful and just as a procession! It is our responsibility and honor to stand with Christ, to process him in public as our King and Savior. When is the last time you talked about prayer or Jesus to a friend or colleague? Does it feel too awkward for you? When was the last time you asked someone not to use your Lord and Savior’s name in vain by shouting “Jesus Christ!” when something surprised them? The virtue of religion, St. Thomas Aquinas tells us, is part of the virtue of justice — that is, giving God what is due to him. We must consider that Jesus’s words in this gospel are telling us about the repercussions of holding this virtue of religion. Shame, spectacle and sacrifice are part-and-parcel of following Jesus and giving God what is due to him. The question is, have we dumbed down what our religion demands to simply “being nice to others?”

If we read the last few verses following today’s excerpt in the 14th chapter of Luke, we hear Jesus tell these same listeners, “Salt is good, but if salt has lost its taste, how shall its saltiness be restored? It is of no use either for the soil or for the manure pile. It is thrown away.” Remember that in the Beatitudes, Jesus tells his disciples that they are the salt of the earth — so clearly his meaning in this reading is that his listeners must retain their saltiness, that is, their openness to sacrifice, spectacle and shame, or be discarded from the Kingdom.

From Aquinas to St. Paul

I’d like to bring up one last lens within which we can examine Sunday’s gospel, and through this lens, make our way to the second reading, St. Paul’s Letter to Philemon. The lens here is to actually challenge the reading above that hate isn’t really hate. What if we follow the Scholastics, St. Thomas in particular, in thinking about hate? In the Summa Theologica, St. Thomas writes, “hatred is a movement of the appetitive power, which power is not set in motion save by something apprehended” (II, ii, q43, a1). To unpack this, what he is saying is that hatred is a movement of the intellect (aka, an “appetite”) that is only set in motion when you apprehend something. In other words, first, hatred is something natural in our soul and intellect, God-given and for a purpose. Second, it’s not a state of being but something that arises in us in response to something we encounter (a thought, a person, a thing, whatever). So, hatred is not an evil thing, but a natural thing, an appetite that we must work to regulate just like all of our other passions and appetites.

Why would God make us with this appetite of hatred, or any of the passions that we tend to regulate poorly, for that matter? In the case of hatred, Thomas tells us, “the object of hatred is evil.” Aha! So, God gives us hatred as a natural repugnance for evil and sin. When regulated well, hatred will turn us from evil and sin.

But regulating this appetite takes prudence and good judgment. After all, Thomas warns us: “Just as a thing may be apprehended as good, when it is not truly good; so a thing may be apprehended as evil, whereas it is not truly evil.” This is why studying and contemplating the truth in the scriptures and Catholic tradition are so important. We train ourselves to better apprehend and recognize good when we see it and evil when we see it.

So why would anyone hate what is good? Because they reject God’s revelation of truth and himself to humanity. Instead, throughout history, people cling to the world around them — what their senses tell them and what passes for “good” in their culture. Is the sound of applause and shouts of praise good? Our senses and culture tell us yes, but Jesus tells us that the meek are blessed because he sees that the cost of fame and recognition is the diminishment of others. Is the pursuit of money good? Pretty much everything in our culture says yes and pretty much everything in scripture says no. What about the flipside of this – what do we mis-apprehend as evil? Let’s think about one of the most common commands in the epistles – to “exhort” and “correct” one another in staying true to the teachings of Christ. But this is difficult to do because nobody likes to be corrected, and our contemporary culture has developed an incredibly robust system of moral idols in diversity and inclusion that make it an evil to tell someone that what they are thinking or doing is wrong. I truly think that today one of the most obvious ways a person can be a spectacle and shame for Christ is to openly tell someone that something they are doing is not morally right or a perspective they are defending is not the truth. In the name of acceptance of others, this is just not OK (so we are told)! But, Jesus commands us to be the salt of the earth, to take up our crosses and be his disciple. Which will you listen to — your culture or your Lord?

But surely our family members can’t be summarily judged as evil and thus worthy of hate! I guess that depends on the culture you live within. For Jesus’s listeners, the cultural voice resided in the Pharisees, Sadducees and scribes, most of whom were in disagreement with him on many aspects of his teaching (especially the core teaching about the conversion of one’s heart to God). Certainly, the broader cultural voices of Rome and of Greek culture were at odds with his teachings. In this context, it likely wouldn’t be too far off the mark to apply hatred towards voices that denied the Good News.

Perhaps referencing family members was way of giving an evocative example of earthly matters. With this reading, we can see that Jesus is being consistent with his other teachings about rejecting the worldly in preference to the spiritual life with God. But, I don’t think this is just rhetorical pyrotechnics. I think Jesus references family members specifically because his Apostles have already had to leave their homes and families to follow him. He has likely seen in the course of his ministry plenty of family arguments, anger and division over following him. This isn’t a hypothetical.

More important than this historico-critical reading of the passage is the understanding that there is a reason Jesus tells us this. The Divine Mind has a plan for our own good, for our reconciliation and union with Him. Remember the first reading: “you had given wisdom and sent your holy spirit from on high … And thus were the paths of those on earth made straight.” So what might this reason be? Jesus tells us time and again that God loves his children — that he will leave the whole flock just to save the one who has strayed — that he welcomes back the prodigal with open arms. All we have to do is to remain faithful to him. This means trusting him and putting him first, above all other concerns (including our family members and other worldly worries). Jesus is reminding us how we have to fulfill our end of the covenant, putting God above all else.

And in return? God perfects us with his grace and his love. He helps us be the loving humans he wants us to be, that he has created us to be. He fills us with his own love and sends us back into the world to love our neighbors (including those family members we judged to “love less” than him). Let’s not think we’re the only ones who are active in our lives! Our part is actually quite small — a continual conversion of heart to God — and then his blessings infuse us and those who we touch in our lives. His is the powerful work in the world, transforming it, not ours.

In other words, the whole point of hating your “own father and mother and wife and children and brothers and sisters” is to allow God to perfect you and give you the ability to love those same people better than you ever could have without his help.

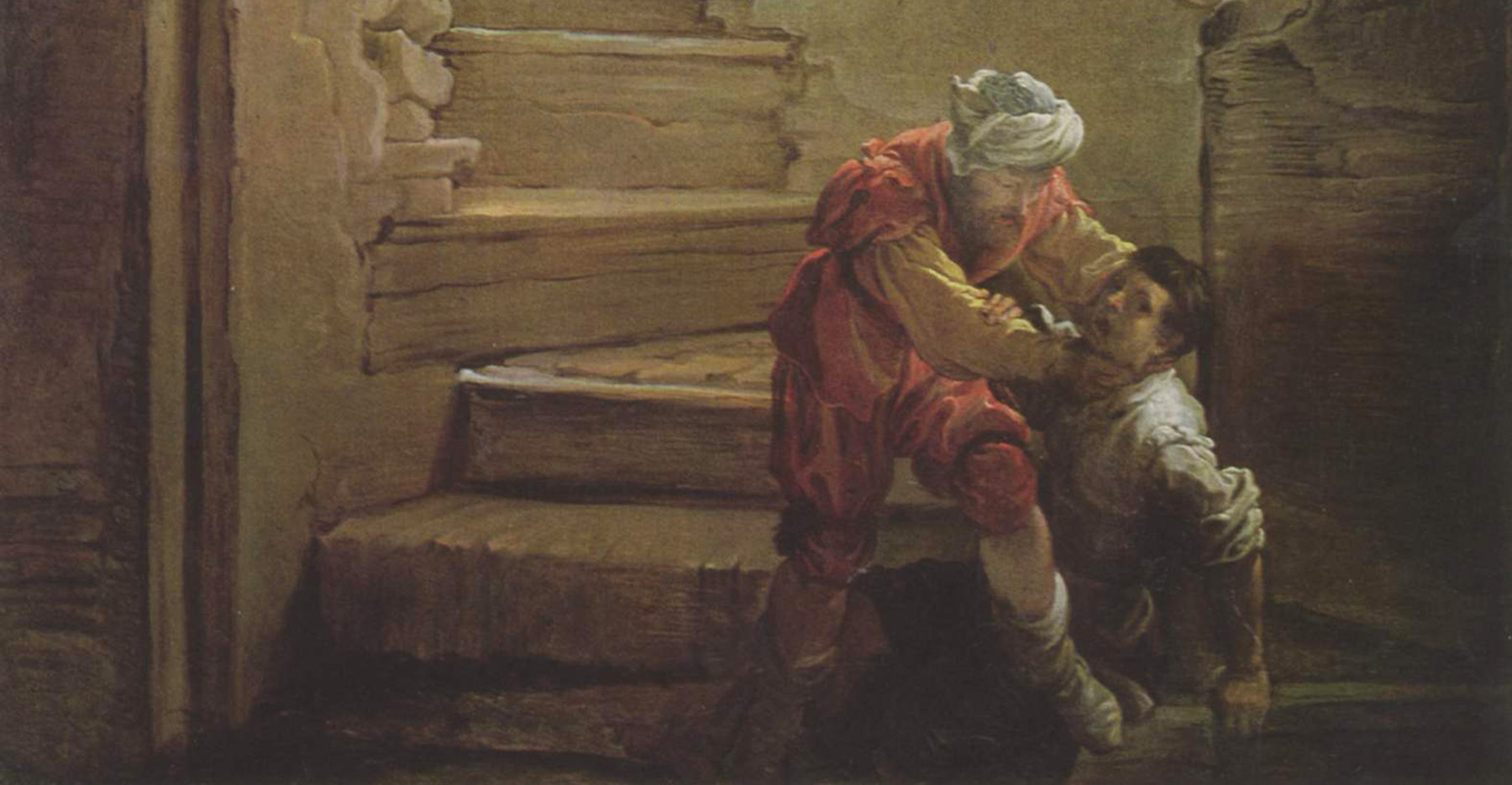

The second reading (the only one in the Sunday lectionary cycle from the Letter to Philemon) is seemingly weird and out-of-context, but blossoms with this understanding of the gospel reading. Paul, writing from jail, is sending Philemon’s slave back to him after this slave, Onesimus, has spent time following Paul and learning about Christ. Onesimus has fled his master, perhaps even owing him money — is this not someone who “hates” his “father”? And, having been nurtured at Paul’s breast, he is returning to his “father” in an act of love by Paul. This is a parallel to what we can read in the gospel account.

Add to this the overtones of Paul’s Letter to the Galatians, where he writes, “So you are no longer a slave, but a son, and if a son, then an heir through God” (Galatians 4:7), and a rich tapestry emerges. In Sunday’s reading, Paul sits in the seat of a redeemed child of God — bearing his cross in jail for proclaiming Christ to the world, but acting with the power of the Father because of it. He sends back a former slave to his family, but not as a slave, but a fellow heir to the Kingdom:

that you might have him back forever,

no longer as a slave

but more than a slave, a brother,

beloved especially to me, but even more so to you,

as a man and in the Lord.

It is now Philemon’s turn to hate the teaching of his culture and the logic of the world, to accept Christ as Paul is urging him to, and to offer his forgiveness to a slave who has so obviously been healed by God. So, if we, like Onesimus the slave, hate our family in order to receive Christ and love him above all else, the divine logic decrees that this enables us to return to our families, even in debt or disgrace, in order to love them with clear eyes and a God-filled heart.

I hope that this contemplation of the Sunday readings have struck a chord with you, that perhaps they have helped move you to approach the gospel with open ears and without the urge to compare Jesus’s words with what we think love and forgiveness should look like.

May you both enjoy your travels. Your move to Spain will be Spain’s gain and our loss. Michael, Hope to meet you both when you visit your parents. Did meet you Michael, previously. You may use our grill again, anytime. We shared your delicious homemade bread at that time.

I agree with the hate….reject explanation, in fact I’m grateful for it.

God’s blessings for you and those you love always.