Monday of Holy Week: Isaiah 42:1-7, John 12:1-11.

As Jesus approaches the Cross in this Holy Week, we glimpse a picture of perfect Christian relationship at the house of Mary, Martha, and Lazarus. It is quickly broken by the duplicitous thoughts and words of humanity dwelling in darkness in the form of Judas. Is this a commentary on the state of the Church until the final judgment? Due to our sinful nature and choices to push away God in favor of ourselves, perhaps the Church will always suffer to have those of unclean hearts attempt to corrupt it.

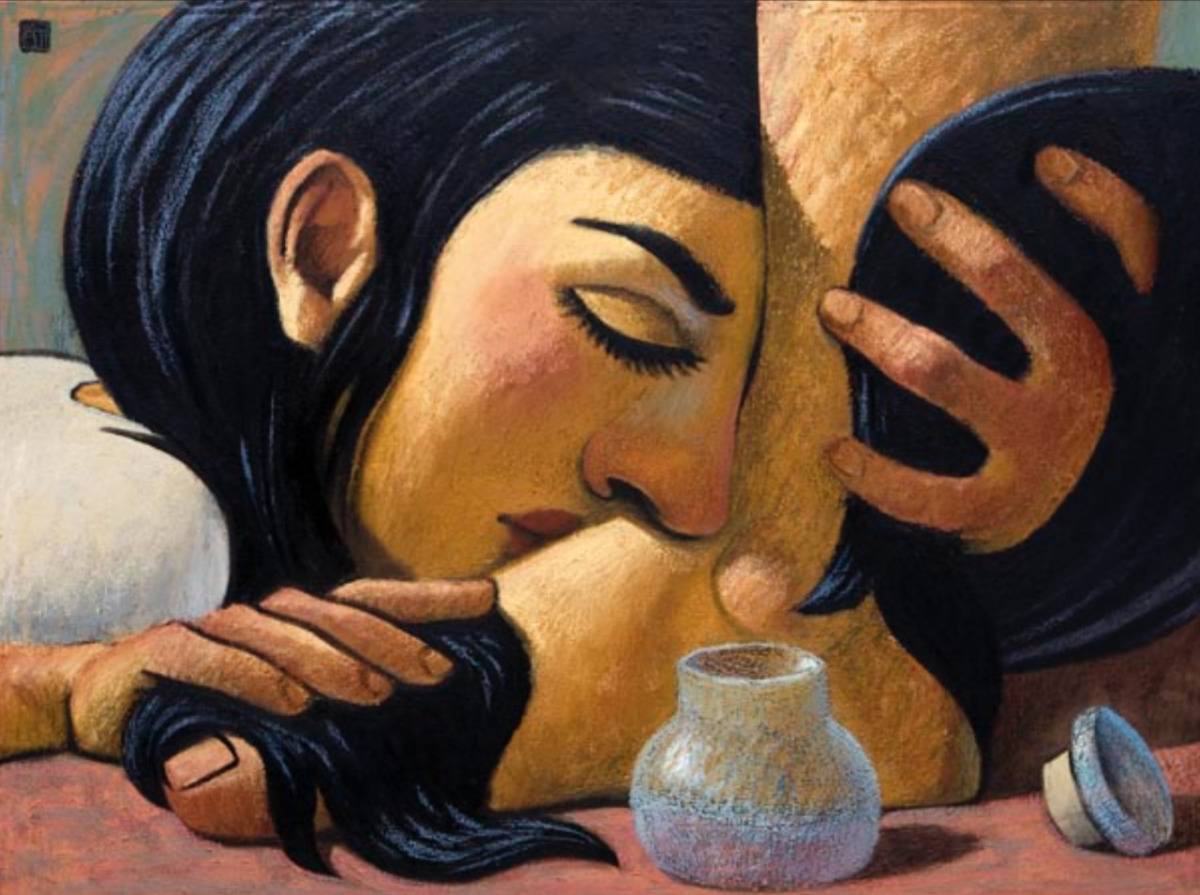

In today’s gospel reading, St. John sets a scene of comfortable domesticity: “They gave a dinner for him there, and Martha served, while Lazarus was one of those reclining at table with him.” This is the Kingdom, here on earth, where the Lord is with those who please Him and serve Him. Lazarus, having been resurrected by Christ, is the symbol of one who has experienced earthly death, but through the grace of God death poses no finality for him; indeed, he reclines in the presence of the Lord. Martha, ever the good servant, prepares and serves the meal. And lest we always cast Mary in the role of the one who lazily lounges in the presence of the Lord, let’s pay attention to the fact that she is the role model for serving, for loving the Lord with all her mind, her heart, and her soul. John tells us, “Mary took a liter of costly perfumed oil made from genuine aromatic nard and anointed the feet of Jesus and dried them with her hair.” This lovely, intimate gesture is one we should examine in more detail.

First, the amount and cost of the oil is clearly extravagant. The Greek text tells us this is a litra of oil, which is actually a Roman measure of a pound, equivalent to 12 ounces in today’s measures (it’s not a liter — I’m not sure why the Lectionary uses this translation). This is still a great amount of something usually used just by wetting the fingertips and rubbing into the skin. The oil is nardou in Greek, translated to nard or Spikenard, a fragrance that comes from a plant growing in the Himalayas, thus foreign and costly. The final clue to the significance of this perfumed oil is hidden in a poor translation. What our lectionary calls “genuine” is in fact the word pistikēs, which translates to “pure.” But more importantly, pistikēs (only used once in the Bible, here) comes from the Greek word pistis, which means faith. As St. Augustine writes,

Whatever soul of you wishes to be truly faithful, anoint like Mary the feet of the Lord with precious ointment. That ointment was righteousness, and therefore it was a pound weight: but it was ointment of pure nard, very precious. From his calling it pistici, we ought to infer that there was some locality from which it derived its preciousness: but this does not exhaust its meaning, and it harmonizes well with a sacramental symbol. The root of the word in the Greek is by us called “faith” (Tractates on the Gospel of John, 50.6).

St. Augustine points out that Mary’s act of using a litra of costly nardou pistikēs is an extravagance of faith. She fulfills the greatest commandment given to us by Christ: “You shall love the Lord your God with all your heart, with all your soul, with all your mind, and with all your strength” (Mk 12:30). This extravagance, despite the poison spit by Judas in the following verses, is completely appropriate in our loving of the Lord. The Old Testament provides verses upon verses detailing the extravagant sacrifices offered to God. Think of King Solomon, who offered “twenty-two thousand head of cattle and a hundred and twenty thousand sheep and goats” at the dedication of the Temple in Jerusalem (2 Chron 7:5). Here we are about to dedicate the new temple, should not our sacrifice be greater?

This brings to mind the sermon of the bishop Saint Andrew of Crete we read yesterday for the Office of the Readings. He says:

Let us run to accompany him as he hastens toward Jerusalem, and imitate those who met him then, not by covering his path with garments, olive branches or palms, but by doing all we can to prostrate ourselves before him by being humble and by trying to live as he would wish. … So let us spread before his feet, not garments or soulless olive branches, which delight the eye for a few hours and then wither, but ourselves, clothed in his grace, or rather, clothed completely in him. … Let our souls take the place of the welcoming branches (Oratio 9, PG 97, 990-994).

Yes, let us spread our very souls before His feet, like Mary in today’s reading. Which brings up the last part of her supplication, that she dried his feet with her hair. She anoints him like a servant, and finishes the act with an intimacy almost like desire or complete supplication, in either case, of one wholly in love. Some readers of the gospel over the millennia have been uncomfortable with the intimacy of this act. They are bothered by the fact that this seems inappropriate, like a desire that approaches eros instead of agape. But there is ample room in the love of God for both the desire we associate with eros and the selfless charity we associate with agape. Think of the sacrament of marriage — clearly eros and desire can be good, not inappropriate. But that’s marriage, you might argue, not our relationship with the Lord. Let’s look to our philosophers of beauty for a foothold here. Following on the heels of Hans Urs von Balthasar, the contemporary theologian David Bentley Hart writes in his book The Beauty of the Infinite, “Beauty evokes desire … [beauty] precedes and elicits desire, supplicates and commands it (often in vain), and gives shape to the will that receives it” (19). We’re not talking about a beautiful face or figure, here. For Hart and von Balthasar, beauty is a transcendent, objective category that defines aesthetics and is inseparable from the identity of Christ and the divine. As Hart describes a certain agency active in beauty, ordering the people who behold it, he goes on to write, “it is only in desire that the beautiful is known and its invitation is heard … the trinitarian love of God — and the love God requires of creatures — is eros and agape at once: a desire for the other that delights in the distance of otherness” (20). What Hart is saying is that if we see the divine Son of God in the figure of Jesus, the pure beauty He presents evokes our desire; it is precisely our desire, our thirst, that God satisfies in us.

To cap this short description of tranquility before the tempest of the Passion, John tells us, “the house was filled with the fragrance of the oil.” To me, this seems to be the fulfillment of Psalm 141, where David sings, “Let my prayer be counted as incense before you, and the lifting up of my hands as an evening sacrifice.” The anointing and bodily supplication of Mary stand in the presence of the Lord like incense, an offering of faith. They perfume the whole house (i.e., the world, the Kingdom here on earth) with their beauty and righteousness. Jesus, who has been surrounded by doubt and constant challenges to his authority and holiness, finally experiences a moment of perfect adoration.

But here the narrative pivots on the sinful presence of Judas. John reports his complaint that the oil could have been sold for three hundred day’s wages and given to the poor, but John tells us more: “He said this not because he cared about the poor but because he was a thief and held the money bag and used to steal the contributions.” What an interesting side note, and I don’t think it’s written just to spite one of the most hated figures in Christianity. St. Augustine explains:

Look now, and learn that this Judas did not become perverted only at the time when he yielded to the bribery of the Jews and betrayed his Lord. For not a few, inattentive to the Gospel, suppose that Judas only perished when he accepted money from the Jews to betray the Lord. It was not then that he perished, but he was already a thief, and a reprobate, when following the Lord; for it was with his body and not with his heart that he followed (Tractates on the Gospel of John, 50.10).

Judas stands there as one who has succumbed to the sin all around us, ironically speaking words meant to stir our consciences. Perhaps not ironically but deviously, because we know that the devil is most convincing and uses everything in his power to entrap us. Judas the thief speaks out of jealousy and greed, wanting those riches poured out upon the Lord for himself. This is the tired tune of sin: to cause violence to the pure and the perfect in covetousness, seeking to turn it back upon oneself. Judas shows that he has no real adoration for the Lord, or really any place in his heart until it’s too late.

Jesus’s response has given some of those committed to social works heartburn over the years. He says, “Let her keep this for the day of my burial. You always have the poor with you, but you do not always have me.” I think this anxiety that God somehow brushes aside concern for the poor is unfounded. First, Jesus knows that Judas is not speaking out of true concern for the poor but out of his own greed and the devil’s work of disrupting a moment of adoration of the Lord. Second, Jesus never suggests that love has a limit, that we only have so much to give so if we have to choose, we give it to God over the poor. In fact, He shows that the love of God is generative, creating more love (think of the loaves and the fishes) and will enable us to care for more of the poor once we attend to God in our hearts. Third, Jesus wants to return attention to the role of God in the world, the salvation He offers, and the transitory nature of our worldly opportunity to dwell with Him. While many a time I’ve wished that I could go back in time to experience the ministry of Jesus, His words here remind us that all of us, regardless of our time in history, have just this period while we are alive to dwell with Him and adore Him. There is something about our passing into the sleep of death, extinguishing the light of life given to us by God, that marks a change for us spiritually. Even though Christ’s work has brought about eternal salvation, we must fully accept his gift in our hearts while still alive in order to gain the eternal life he offers to us.

One last remark: let’s consider that Jesus tells Judas to leave Mary to save the oil for his embalming (the literal translation of the Greek). This has meaning of course on the literal level but also on the symbolic. The costly, pure, aromatic oil is faith and adoration, desiring to be with God and love Him completely. Jesus not only reminds them all of his upcoming death but of the work that must continue on their part to establish the Church. Mary and the rest of his disciples must anoint his Body (the Church) with faith and the desire for God. They must pour it out lavishly, just as she did here at the feet of Christ.

We see the beginnings of the Church in the final verses from the gospel: “The large crowd of the Jews found out that he was there and came … And the chief priests plotted to kill Lazarus too, because many of the Jews were turning away and believing in Jesus because of him.” The chief priests, like Judas, like all who seek to disrupt and discredit our Christian faith, will seek to kill not just Jesus, but his works and his followers. We, the Church, should be ready for this and meet it with the same lavish outpouring of love our God has given us.