Today is the Solemnity of the Most Holy Body and Blood of Christ — aka, the Feast of Corpus Christi. We were fortunate to celebrate Mass in Park City at St. Mary’s Church, presided by Fr. Chris Gray, who is about to be transferred to the Cathedral of the Madeleine in Salt Lake City to serve as rector, and undoubtedly become a Monseigneur or even greater someday. He’s a great priest. He’s likeable, has a great singing/chanting voice, is funny, but most importantly, has a great reverence for the liturgy. So, in addition to a meaningful homily and prayerful sacrifice of the Mass, we enjoyed a Eucharistic procession around the church and a benediction, complete with incense and chanting of St. Thomas’s Tantum Ergo Sacramentum.

This solemnity is the great marker of the Catholic faith; a dividing line between Protestants and Catholics. We believe that in the Eucharist the Body and Blood of Christ are really and truly present — mystically and spiritually available to us in all their power and glory. Protestants believe that Jesus was speaking symbolically when he said the bread and wine were his body and blood. Why does this matter? Because if we want to follow the entire Way given to us through Christ, we can’t ignore the sacraments and the Eucharistic miracle he gives us. (The early Church was unanimous in believing in the real presence of Christ in the Eucharist. Heck, in 110 AD, St. Ignatius of Antioch told the Smyrnaeans to “keep aloof from” the heretical Gnostics “because they confess not the Eucharist to be the flesh of our Savior Jesus Christ” (Epistle to the Smyrnaeans, 7).) The sacraments are the way his Spirit is active in the world. Would you dare not believe in the power and work of the Holy Spirit?

Since the Council of Trent, the Catholic Church has affirmed that “for believers the sacraments of the New Covenant are necessary for salvation” (Catechism of the Catholic Church, 1129). Protestants believe nothing of the sort. It seems to me that theirs is a passive religion when it comes to salvation — taken in passively by grace and faith alone. In comparison, Catholics are taught that we have an active role in receiving grace, through the sacraments and in love and charity of God and neighbor.

But something else stuck with me as I contemplated today’s readings and the significance of the solemnity. When Protestants say the Eucharist is just a “symbolic act,” they are in fact missing the depth of the symbolism. We, too, believe it is a sign — the greatest of all signs — but the significance of the sign is that it points to a new reality. So, I’d like to blog this Feast of Corpus Christi about the intersection of sign, symbol and reality as well as the unique and troubling (for some) insistence of Jesus Christ that we eat his actual body and blood.

Sign, Symbol and Reality

It can be confusing to talk about signs and symbols because they’re often lumped together. Unless you’re a semiotics professor, we all sort-of shoot from the hip here. (The academic field of semiotics that started perhaps with the ancient Greeks but blossomed in the second half of the 1900s is dedicated to studying sign, symbol, meaning and the like, but if there was ever a field that felt like splitting hairs, it’s semiotics.) Let’s first acknowledge that these words definitely overlap and share meaning, and not just in English, but also in Greek, Latin and Hebrew:

| English | Latin | Greek | Hebrew |

| sign | signum | σημεῖον (sēmeion) | סִימָן (siman) |

| symbol | symbolum | σύμβολον (symbolon) | סֵמֶל (semel) |

Despite the difficulties involved, I’d love to lay out a general difference between sign and symbol for the purpose of this blog. Let’s take a cue from the Latin signum, which is something that marks or identifies. An everyday usage could be something like a military signum in the form of a battle standard, and a supernatural signum would be a heavenly sign or miracle. We can see where we get the word signature (a personal “mark” that identifies the signer). I like also to think of a road sign, which points towards something. Taken together, let’s think of “sign” to mean a material thing that points to something else that holds extra meaning. So, when we make the sign of the Cross, it means more than just cross-shaped gesture around the face and chest area. It’s a sign of following Jesus Christ.

“Symbol” has an interesting history, too. In the ancient world, the Greek word symbolon described an object like a piece of parchment, a seal, or a coin that was cut in half and given to two parties. It established a relationship between them. When the halves of the symbolon were reassembled, the owner’s identity was verified and the relationship confirmed. To take poetic license with this etymology, we might say that a sign is like a signature, but a symbol is only half the story (half the signature). It points to something even more complex: a relationship to a shared history.

As a short side note, the early Christians and Church Fathers called the Creed they developed in the Council of Nicea and further councils as the “symbol of faith” or just the “Symbol.” This reveals that they saw our Creed as a way to recognize another Christian, and that a shared relationship is at the heart of our faith (shared with Christ and shared with one another as the Church).

In our language, we’ve applied the deeper, more abstract meaning of “symbol” into words like symbolism, which implies a shared cultural story that lies behind the symbol. To sum up, I think “sign” is more direct, although still pointing to something outside itself (we say, “what does that signify?” and we expect a direct answer). I think “symbol” is a bit more complex and abstract, pointing to something more like a shared story of significance (we say, “what does that symbolize?” and we push our minds to think of things like metaphor, analogy, and mythological and religious stories).

These terms have a deep history in our faith tradition. Circumcision is a sign of being a Jew, but it is a symbol of a circumcised heart — a life dedicated to God and living within his laws and precepts. Burning incense in our churches is a sign of reverence to our Holy God, and it is a symbol of our prayers rising up to Him in Heaven, as well as a symbol of immolating something precious to us as an offering to the Lord according to our covenant with Him. Importantly, signs and symbols in our religious tradition are material things in the world that point to spiritual realities we cannot see, touch, or otherwise sense. They help our physical humanity interact in some way, no matter how diminished, with something greater and immaterial. As St. Thomas writes: “Signs are given to men, to whom it is proper to discover the unknown by means of the known” (Summa Theologica, III, 60.2). I love the fact that he says signs are “given” to us, reminding us that there is logic and intentionality in the way God created the universe, even down to knowing how we might apprehend material things in the world and apply signification of greater things to them.

This idea that signs are a bit more straightforward and symbols are a bit more complex gets turned on its head when it comes to the sacraments. This is because, as signs, they point to the mystery happening in our midst.

The Church teaches that the sacraments are the greatest of signs in our faith lives because they transcend being signs and actually have real spiritual effects within us. Even just at face value, each sacrament is more than a typical sign, which is a single material object or action. In their execution, the sacraments include a form of the liturgy specific to each — that is, the prayers, movements, and physical items used in each rite. So a sacrament includes a number of other “signs” within it, such as water, candles, incense, etc. For instance, water is a sign of spiritual purity, but when water is used in the sacrament of Baptism, that sign takes on more meaning and contributes to a larger understanding of the “sign” of the sacrament of Baptism. Likewise, the Eucharist has the material appearance of bread and wine, but those symbols/signs are part of a larger liturgical movement that calls down the Holy Spirit in sanctification and intones a shared set of prayers between priest and believers. The whole sacrament, then, is a “sign,” but is so much bigger than other types of signs.

It’s hard to overstate just how deep and important the sacraments are as signs. The Catechism of the Catholic Church sums up a discussion of the sacraments with the words of St. Thomas: “Therefore a sacrament is a sign that commemorates what precedes it – Christ’s Passion; demonstrates what is accomplished in us through Christ’s Passion – grace; and prefigures what that Passion pledges to us – future glory.” As a collection of material signs, prayers and action of the Holy Spirit, a sacrament is a sign that “points to” many other symbols and signs in salvation history at the same time it is doing active spiritual work through the power of the Holy Spirit.

All of this sets the stage for discussing the Eucharist on this Feast of Corpus Christi. As I thought about the great sacramental sign of the Eucharist, three aspects jumped out at me: how the bread and wine are a symbol of — and somehow the reality of — manna, the sacrificial Lamb, and the true Body and Blood of Christ.

Bread of Affliction, Bread from Heaven

The Passover figures greatly in a full understanding of the sacrament of the Eucharist. Perhaps the best exploration I’ve read is Brant Pitre’s Jesus and the Jewish Roots of the Eucharist. Highly recommended. I’ll do my best to summarize a few things here.

One of the seemingly smaller aspects of the Jews’ flight from Egypt is bread. On the original Passover night, the Jews had to get ready to move quickly because after the angel of the Lord passes by their homes and slaughters the firstborn throughout the land, they must hightail it out of Egypt. This means they don’t have time to let their bread rise with yeast and they have to bake and eat unleavened bread during their flight.

Moses enshrines the memory of the Exodus in the Festival of Unleavened Bread: “For seven days you shall eat unleavened bread with [your Passover sacrifice] — the bread of affliction — because you came out of the land of Egypt in great haste, so that all the days of your life you may remember the day of your departure from the land of Egypt” (Deuteronomy 16:3). So much can be said about this “bread of affliction”! The bread made by human hands, out of necessity being less than satisfying — what a great symbol of our metaphysical state of being separated from God. The act of intentionally depriving ourselves of material comfort — a great parallel with the intentional deprivations practiced by saints and monastics thousands of years later.

But there is more to be said about bread as a symbol.

Wandering in the wilderness after they fled Egypt, the Israelites complained to Moses that they were hungry. God showed his love by raining down bread from heaven to sustain them. “The house of Israel called it manna; it was like coriander seed, white, and the taste of it was like wafers made with honey … The Israelites ate manna forty years, until they came to a habitable land” (Exodus 16:31, 35). Unlike the bread of affliction, the manna from heaven is both pleasing to the senses and extremely nourishing. Bread as a symbol had been sanctified. But sanctified bread came only from God, it was not something that could be made by humans.

After the Exodus, bread would never again be “just bread” for the Jews. It would always also be a symbol of God’s love for them and his commitment to them. God chooses good symbols; bread sustains life, and he was training them to understand that he sustains life even more fundamentally than physical food. By the time of King David, 450 years later, they had memorialized manna as more than normal bread: “he rained down on them manna to eat, and gave them the grain of heaven. Mortals ate of the bread of angels; he sent them food in abundance” (Psalm 78:24-25).

And 1,000 years after David, when Jesus perfects our understanding of God’s law and the words of the prophets, he deepens this reference to manna: “[My flesh and blood] is the bread that came down from heaven, not like that which your ancestors ate, and they died. But the one who eats this bread will live forever” (John 6:58). Jesus brought something new and shocking to the already-rich symbol of bread. God allowed the symbol to convey meaning for many centuries specifically so he could invoke all that the symbol of bread stood for and use that image to point to a new reality in our midst. Note what is going on here! It’s a reversal of how material signs usually operate in our entire way of building meaning. Until this moment, the material sign of bread was a pointer to something deeper, a symbol of God’s love and commitment. Jesus himself used this conventional symbology during his miracle of the loaves and fishes, when the bread demonstrated God’s inexhaustible and overflowing love for humanity. But now, the rich symbol is used to point to a new material and spiritual thing. In other words, usually things act as symbols pointing to complex concepts, but here the complex symbol is pointing to a thing. A very corporeal and perfectly spiritual thing that is Christ’s actual flesh and blood.

I’d even argue that it had to happen this way. Only with a symbol that was so richly endowed could Jesus teach us about the mystery of the gift he was giving us. He’s saying to us, “Even with how awesome you thought that manna given in the Exodus was, the gift of my flesh and blood for you to eat is the real bread of heaven because it does more than keep you alive in this world.”

Bread is still a material thing, and it’s still a symbol with a rich history of meaning, but now that symbol is pointing to something new, a new thing, the reality of the Eucharist.

The Sacrificial Lamb

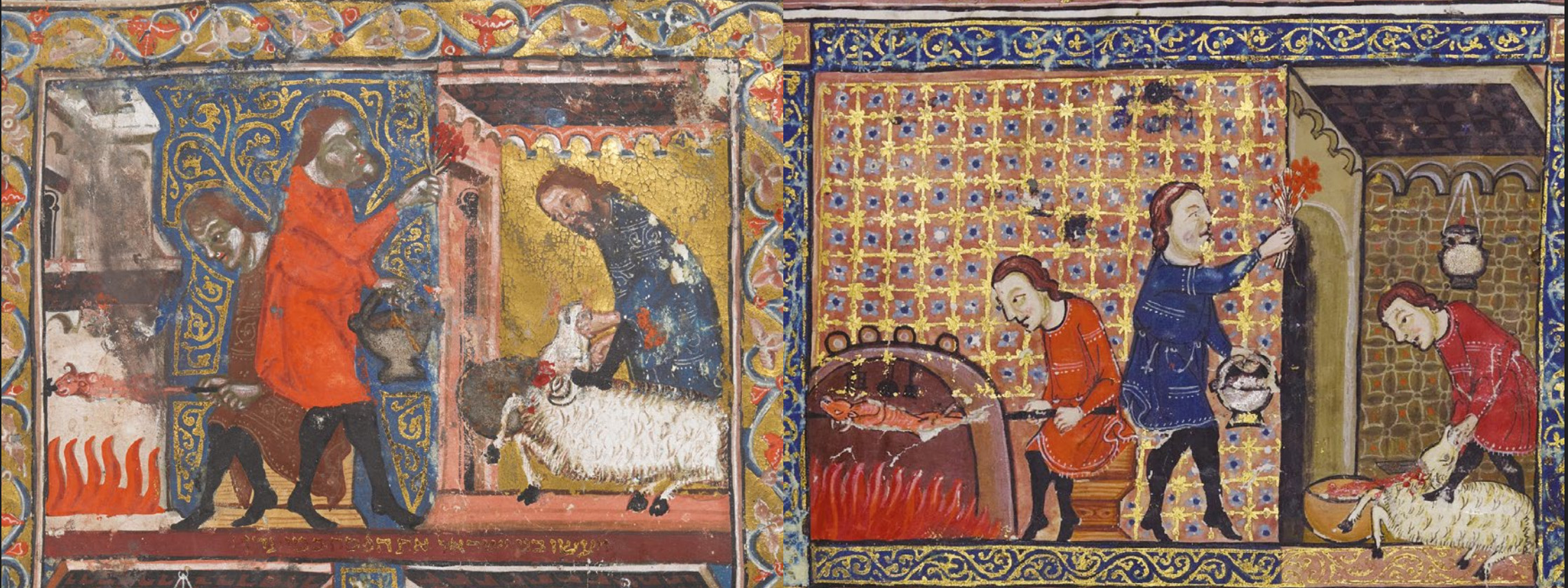

Much like bread, the sacrificial lamb has thousands of years of meaning attached to it for the Jewish people. All the way back to Abraham, we have the willing but difficult sacrifice of the son, replaced by the ram provided by God. But the sacrificial lamb really becomes codified in the lives of Jews during the Passover, when each family takes an unblemished lamb (from the sheep or goats) and “the whole assembled congregation of Israel shall slaughter it at twilight. They shall take some of the blood and put it on the two doorposts and the lintel of the houses in which they eat it. They shall eat the lamb that same night” (Exodus 12:6b-8a). The lamb here is an interesting mix of symbol (much more than just a lamb, it is a symbol of fidelity to God’s command) and physical sustenance. We really see the roots of the Eucharist clearly — in a ritualized way, believers gather as a community to slaughter the lamb as a sacrifice to God, then eat it.

Famously, the Jewish faith includes a lot of animal sacrifice. Sin offerings were a common form of sacrifice and this particular ritual is important for Christians to understand because the phrase “He died for our sins” very much refers to this practice. God told Moses that they must make regular offerings as a payment of sorts for their sins. God prescribed that “The sin offering shall be slaughtered before the Lord at the spot where the burnt offering is slaughtered; it is most holy. The priest who offers it as a sin offering shall eat of it; it shall be eaten in a holy place in the court of the tent of meeting. Whatever touches its flesh shall become holy” (Leviticus 6:25-26).* Note the insistence of the holiness of the event and the offering, which is again eaten. Strikingly, the ritualized sin offering is transformative — “whatever touches its flesh shall become holy.” We can locate a number of things in our religion that echo this transformational aspect of the sin offering: primarily, the Eucharist, which is the new offering for sin that we eat and which transforms us into something holy, but also things like holy relics of the saints, from which we have seen miracles transmitted.

So imagine what must have been dawning on the Apostles, who were brought up with the rich symbology of the bread and the rituals of the sin offerings with an unblemished lamb, when “On the first day of Unleavened Bread, when the Passover lamb is sacrificed” (Mark 14:12), they were led to the upper room for him to institute the Eucharist during the Last Supper. Surely, some of them remembered John the Baptist declaring when he saw Jesus, “Here is the Lamb of God who takes away the sin of the world!” (John 1:36). They were told he was the lamb who was going to produce some sort of never-before-seen, world changing sin offering!

Sure enough, Jesus uses the sign of the lamb, as well as those loaded signs of bread and wine, to point back to himself, the nearly unfathomable mystery of salvation for all of humanity. “Jesus took a loaf of bread, and after blessing it he broke it, gave it to the disciples, and said, ‘Take, eat; this is my body’” (Matthew 26:26). He sanctifies and sacralizes the bread, meaning that he makes it holy with his own essence and by his own divine power, then tells them to eat it, just like they eat the flesh of the Passover lamb. And why is the wine used? “Drink from it, all of you,” he says, “for this is my blood of the covenant, which is poured out for many for the forgiveness of sins” (Matthew 26:27-28). It is used because the sin sacrifice requires real blood, real suffering.

We might ask why not use actual sacrificed lamb meat as the Eucharist during the Last Supper? I’ll offer a theory (Aquinas offers his own). I think there had to be a physical and mental break with the traditions of the Old Testament. Jesus was instituting a new covenant where he was going to be sacrificed, not a lamb. The “remembrance” of this great event is more fittingly placed in the symbols of bread and wine, which were symbols of a covenantal relationship with God and signs of God’s abundance. What’s more, the difference of Christ’s flesh is accentuated here — the God-man’s flesh cannot be appropriately signaled by actual meat of any sort. Jesus Christ’s body is united not just with a spirit, but with God’s Spirit. Meat would be too similar and encourage us to fall too short of recognizing this great difference.

Truly Eating Flesh

In the gospel of John, when Jesus tells the crowd, “the bread that I will give for the life of the world is my flesh,” the Jews don’t react well, saying, “How can this man give us his flesh to eat?” (John 6:51-52). Does Jesus back off a little and say, “I’m speaking symbolically”? No! He doubles down. He says, “Very truly, I tell you, unless you eat the flesh of the Son of Man and drink his blood, you have no life in you” (v.53). He is insistent on this point, which sounds a heck of a lot like cannibalism to ears not prepared for it and hearts not realizing that this is God speaking.

And as if to punctuate the literal nature of what he means, Jesus adds, “Those who eat my flesh and drink my blood have eternal life, and I will raise them up on the last day” (v.54). But English fails us here, because in verse 53 he uses the common Greek verb for eating, “phagein” (φαγεῖν), while in verse 54 he ups the literalness and uses the verb trōgō (τρώγω), which means to gnaw, munch, or crunch. Those who gnaw on my flesh!!

As if he’s not shocking enough, he’s also claiming to be able to give eternal life through this eating of his flesh. The divine power of the Eucharistic sacrament is laid bare. But it’s only available to those who are willing to eat his literal flesh. Very truly, I tell you!

People call the gospel of John the most theological and the most symbolic. With the confluence of these two ideas, we see what Christianity is all about: we know God through a highly symbolic language that points to new realities, new things. Again, if what Jesus is doing is reversing the typical “sign /symbol is a physical thing pointing to a complex idea” into “complex sign/symbol is pointing to a new physical thing” (i.e., his flesh in the Eucharist), then this is precisely why our theology is the opposite of a mythology. Myths are stories to help us understand our world and experiences, but Christian theology is the exploration of God revealing himself to us as reality itself. Traditional sign/symbol meaning making is great for talking about ourselves and our experience, but God saw fit to use symbols in a new way: to help us access his own infinite reality.

Thinking back on our celebration of the Feast of Corpus Christi, these thoughts were swirling around in my head as I listened to Fr. Gray’s homily and prayed with the congregation during the consecration of the Eucharist. The Eucharist contemplated and received can be an emotional thing. And I was contemplating what emotions Jesus may have wanted us to feel when gnawing on his unbloody flesh in the form of the host and the wine. Why insist that we physically interact with his flesh in this way? Why be a sacrificed lamb, whose holiness spreads to everything it touches but is at the same time unapologetically messy in its grease and juice and chew?

I have been taught to feel joy and thankfulness for this incredible gift of the Eucharist. I have imagined it sanctifying my mouth, my esophagus, and my stomach as well as my soul as I ingest it. Aquinas teaches us that the great difference between this food and other food is that instead of us turning the food into ourselves (by nourishing our cells and organs), the Eucharist helps turn us more and more into Christ. I love this teaching and love approaching the Eucharist with this in mind.

But, for the first time, I felt something different. As I considered the bloody sacrifice of the Cross and Christ’s insistence that we eat the flesh of this sacrifice, I had a catch in my throat. The moment when we as a congregation shout “Crucify him!” during our Good Friday Mass of the Passion came flooding back to me and my culpability as a sinner unfit for unity with He who is all good came over me. My eyes threatened to tear as I thought about the sheer sorrow of having to eat of a sacrifice that humanity made necessary through our initial disobedience and stubborn stupidity when he came in bodily form. There is something of the gag reflex here — of choking on something that is both sweet and horrible. Horrible not because of taboo (as in cannibalism), but horrible because we needed such a sacrifice. Horrible because that suffering of that very real savior Jesus Christ actually happened, and we remember that when we proclaim the Eucharist to be his very real presence.

Of course, God transformed our sorrow into awe and joy with the Resurrection, and this is the point of sharing in the Eucharist — sharing in the Resurrection. So, I didn’t dwell on that feeling of self-repulsion, because I don’t think it reflects what this sacrament is all about. At the same time, I think it was a positive experience. I think there are infinitely plumb-able depths to the reality of the Eucharist that is pointed to by our simple signs of bread and wine. I think Christ’s insistence on actually eating his flesh is something we need to take seriously and contemplate.

And I thank God for the fact that his Son’s flesh is made unbloody and spiritual in our sacrament. I praise him for his wisdom and his gentleness with us, who condemned his Son to death, only to desperately need his saving Body and Blood so that we can partake in the Heavenly banquet that is everlasting life with him.

* Note: it is worth re-reading chapter 23 of Leviticus, where God teaches Moses how to celebrate festivals, or “holy convocations” to honor him. These are the seeds of the sacraments as we know them today: liturgical rites with specific practices and gestures that endured for 1,500 years before Christ instituted the New Covenant. The “sign” of each sacrament points back here (indeed, back to Abraham and Isaac), and simultaneously points to Christ’s life, work, death and Resurrection, as well as pointing to the everlasting life to come.