Pentecost is one of our highest feasts — marking the anointing and confirmation of the Church by the Holy Spirit. It is a true turning point for humanity, when God begins to interact with us in a new way. The Church’s liturgy for Pentecost is so full of the mystery surrounding the action of the Holy Spirit that it provides us with a dazzling array of Scripture to shed light on this event. The Vigil Mass has an extended form, much like Easter Vigil. Through four Old Testament readings and associated psalms, it reminds us how the Spirit has been guiding us and transforming our activity into something holy from the beginning of time. We hear of humanity’s hubris in the Tower of Babel, a symptom of our fallen state that God remedies by confusing our language. Lest we think that God is a malevolent God, doing this to spite us, he promises us through the prophet Joel, “I will pour out my spirit upon all flesh. Your sons and daughters shall prophesy … Then everyone shall be rescued who calls on the name of the LORD.” Of course, this is realized at Pentecost when the Spirit descends on Mary and the Apostles and reverses the confusion of Babel.

But it’s more than just a loosening of tongues. Those tongues have something new to proclaim. We have become intelligible to one another once again, but only in a specific mode: allowing the Spirit to talk through us, to tell us about the Triune God and his saving plan for us through the person of the Son.

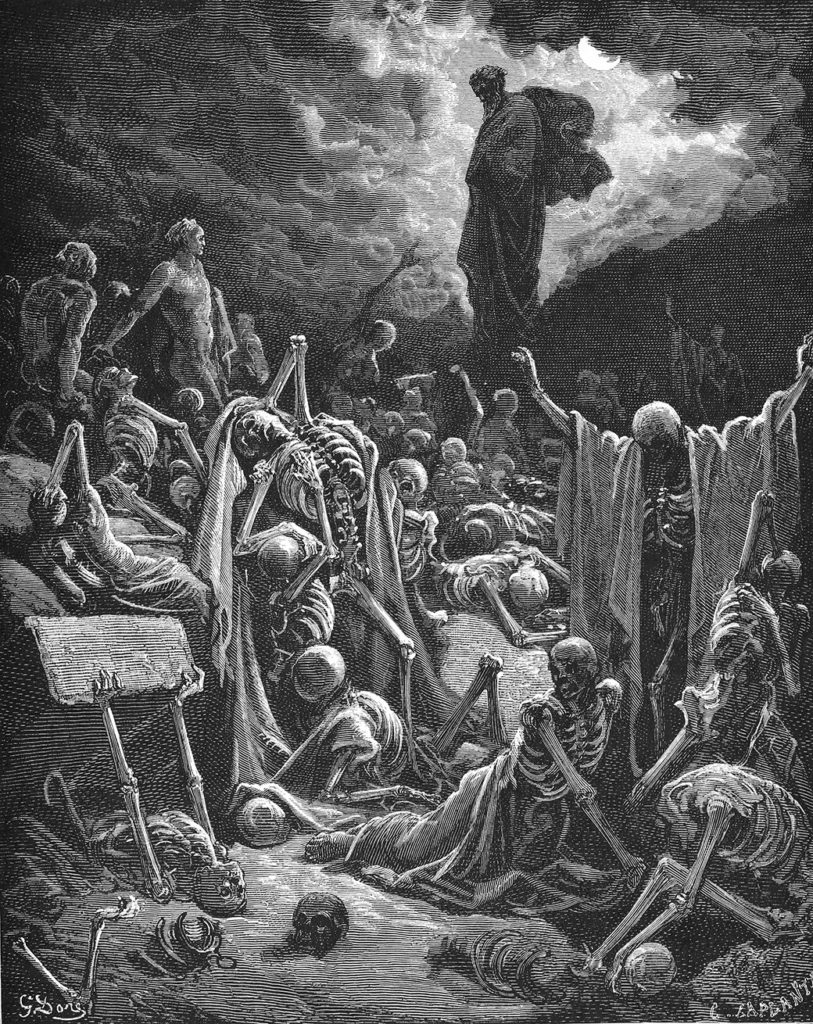

The incredible reading from Ezekiel in the valley of dry bones is an astounding prophecy of the Pentecost in the upper room in Jerusalem. God tells Ezekiel, “Prophesy over these bones, and say to them: Dry bones, hear the word of the LORD!” Note how this foretells exactly what will happen. The “dry bones” of the Jews and Gentiles hear the word of the Lord from the mouths of the Apostles, the new prophets of a new age. God assures Ezekiel that his word will be efficacious. God tells the bones, “See! I will bring spirit into you, that you may come to life.” Indeed, Ezekiel sees sinews and flesh cover the bones as they stand, “but there was no spirit in them.” Now, note carefully — God tells Ezekiel to pray to the Holy Spirit: “Prophesy to the spirit, prophesy, son of man, and say to the spirit: … come, O spirit, and breathe into these slain that they may come to life.” How surprising! I find it more than a little striking within the Jewish context that the God who time and again reminds them that he is the one and only God, the Creator, tells his prophet Ezekiel to turn his appeals to the Holy Spirit. This is one of several times in the Old Testament, in fact, that when we read carefully, we see that God is telling us something about himself, about the three persons of the Trinity. It would take centuries until the Councils of Nicea and Constantinople could properly articulate an understanding (dumbed down for our human intellect) of the Trinity having one and the same essence of a single God, but three distinct persons in the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. Nonetheless, we can trace their distinction to moments like these in Ezekiel and even to the creation story itself where God tells us that it is him, but also his Word and his Breath that act in creation in different ways.

I want to take a moment to reflect on the person of the Holy Spirit. I think many of us might be quietly (and innocently) caught in a type of subordinationist heresy. Simply put, this means that we have the tendency to think that God the Father is hierarchically the main and most powerful person of the Trinity — effectively subordinating the Son and the Holy Spirit to being lesser than him. Don’t fret, we would be in good company because several early Church Fathers like Irenaeus, Tertullian and Justin Martyr were also likely subordinationist, but that’s because the Church hadn’t yet been forced to think hard and long about the relationship between the persons of the Trinity. That was foisted upon the Nicene Council by Emperor Constantine I to figure out in the year 325 A.D. In fact, it was the more serious heresy of Arianism, where Jesus was taught to be a created being, that was the cause of the council, but the effect was the same — the council came up with our formulation that we repeat in our Creed to this day, where the Father, Son, and Holy spirit are proclaimed to be consubstantial with one another. That is, of one and the same essence.

Perhaps it’s because of some of the references to the Spirit in Scripture might make us feel that it is not as, I don’t know, approachable (?) reliable (?) as the Father. For me, it’s when Jesus tells Nicodemus, “The wind (pneuma) blows where it chooses, and you hear the sound of it, but you do not know where it comes from or where it goes. So it is with everyone who is born of the Spirit (Pneumatos)” (John 3:8). This passage leaves me with a sense of flightiness about the Spirit (although I think that’s erroneous). Plus, the Apostles are waiting in the upper room for the Spirit to come, and it seems like no one knows when it will come. So, we don’t know where it comes from, when it will come, or where it will go next. A heretic might say that this Spirit sounds unreliable. But Jesus tells us emphatically that “everyone who speaks a word against the Son of Man, it will be forgiven him; but he who blasphemes against the Holy Spirit, it will not be forgiven him” (Luke 12:10). So, let us never say that the Spirit is unreliable!

Turning back to Scripture, of course, we find that the Spirit is both efficacious and reliable. If Ezekiel on the plain of bones isn’t convincing enough, we have the Word of God, Jesus, who tells us, “It is the Spirit who gives life” (John 6:63), and in reference to reliability, “how much more will your heavenly Father give the Holy Spirit to those who ask Him [than those who are evil and also fulfill promises]?” (Luke 11:13). We learn from Jesus that the Spirit gives us life, which is why we baptize in his name, and the Spirit is the one who speaks through us when we are blessed by God. The Spirit is the Father’s way of acting in and through us. All of this is possible because the Holy Spirit is God’s actual spirit! But I don’t know if that helps clear up the subordinationist heresy. A person’s spirit certainly seems to be an integral, if not central, part of oneself. But it’s not that whole self, is it?

This is where we go wrong — using ourselves as a reference point to try to understand God. We should always go the opposite way and use the mysterious truth God reveals about himself to better understand ourselves.

This Pentecost, I really leaned on correcting any misconceptions I was harboring about the Holy Spirit as a secondary divine player. Some of this was reflecting on the work of the Council of Nicea in affirming that the Spirit is the same exact divine essence of the Father and the Son. Another was a re-reading of the opening of the Letter to the Hebrews, where the Holy Spirit speaks through the writer (St. Paul or one of his followers) with this astounding and clear proclamation: “[The Son] is the reflection of God’s glory and the exact imprint of God’s very being” (Hebrews 1:3). I’m not presuming to tackle one of the most difficult fields in all of theology in understanding the mystery of the Trinity, but there is one point that my brain was able to process here. Being of the “same essence” is a technical way to talk about being “the exact imprint of God’s very being.” This phrase from Hebrews is very specific and resonates with me differently.

If we apply the “exact imprint” thought to the creation scene, we might see something different. When God creates Adam, he “breathed into his nostrils the breath of life” — this breath is his Spirit (rukah in Hebrew and pneuma in Greek refer equally to breath, spirit and wind). This is not a metaphor, it is a way that God is revealing the mystery of the Trinity to us. The action of a human breathing might bear some resemblance to God breathing, but only a shadow of it. The Father is so superabundant and generative that when he breathes, his breath contains all that he is. This is no normal exhale. This breath is God sharing his very essence, so strongly that this essence has its own personhood and action in Creation. In the same fashion, the Word is from God, and it is also fully God, a personhood of his essence who is active in the world in a special way. This Creator who can make all of Creation with a Word and a Breath imbues his essence into everything simply by thinking about it! His presence is so overwhelming that just a whiff of his essence could spawn a thousand galaxies (although everything he does is intentional and intelligible, as his Word and law attest). Imagine what his actual, full Spirit can do!

These are things we cannot do — imbuing our very selves in our breath and world — and we have no power to create and inspire and be truth. And yet, by the grace of God we actually can create some things (physical, emotional, mental) and we can inspire one another, and we can speak the truth, all just in an infinitely reduced way compared to God. Do we pride ourselves in our little godhood or do we recognize that what we are sharing in is a gift from the one who created us? Can we realize just how much greater God’s power is than our little triumphs in life?

More importantly, are we doing the good that God wants us to do? I want to shift from thinking about how the Spirit is fully God to thinking about how important it is that God is giving his full self to us now in the End Times. We receive the Spirit as much as the Apostles in the upper room did, albeit the way this manifests in us is different. While the Spirit is present in all of our Sacraments, Baptism and Confirmation confer on us a personal evangelical call that we too often ignore. Consider what happened to the Apostles when the Holy Spirit descended on them. We are told in the first reading of the Pentecost liturgy during the day, “And they were all filled with the Holy Spirit and began to speak in different tongues, as the Spirit enabled them to proclaim” (Acts 2:4). What did they proclaim? The rest of Acts chapter 2 relates Peter’s great homily, where he proclaims, “This Jesus God raised up, and of that all of us are witnesses. Being therefore exalted at the right hand of God, and having received from the Father the promise of the Holy Spirit, he has poured out this that you both see and hear” (Acts 2:32-33). Here’s the nugget! The Spirit is poured out so that the Apostles can share the saving truth that God worked through his Son, Jesus Christ.

The Spirit is not poured out simply to make them feel emboldened or to grace them for being good people. There is a purpose, because now the End Times have begun and all of humanity is given some time to turn their hearts to the Way, the Truth and the Life before the Last Judgement.

Note how the Letter to the Romans acknowledges this moment that we still live within, found in the Pentecost Vigil epistle reading:

We know that all creation is groaning in labor pains even until now;

and not only that, but we ourselves,

who have the firstfruits of the Spirit,

we also groan within ourselves

as we wait for adoption, the redemption of our bodies. …

the Spirit too comes to the aid of our weakness;

for we do not know how to pray as we ought,

but the Spirit himself intercedes with inexpressible groanings.

In other words, the whole point of life is the “adoption, the redemption of our bodies,” when we will be reunited perfectly with God. We — indeed, all of creation — are groaning in the labor pains brought about by Christ’s life, death and resurrection. And the Spirit is here to help us during this time, filling our mouths with the saving message of Jesus Christ, which gets us to this adoption, i.e., Heaven.

Let’s repeat this: the Spirit is given to us (today, in our Sacraments and freely by grace) specifically to fill our mouths with the redemptive message of Jesus Christ — intelligible in all languages and meant for all people. We are supposed to be sharing the Way, the Truth and the Life with others. This is what it means to truly love your neighbor. I meet so many Christians who think loving your neighbor means good deeds, kind words, and a helping hand. But without the message of Jesus Christ, who was literally raised bodily from the dead to create a new path to salvation for us, these good deeds are meaningless. Because the point has never been this life or making things better in this world. The point has always been to do God’s will, which is absolute goodness and truth, so we can be as worthy as possible for the redemption he is holding out to us. How can we have fallen so far from this message?

The second reading on the Pentecost liturgy celebrated during the day makes this point crystal clear: “If the Spirit of the one who raised Jesus from the dead dwells in you, the one who raised Christ from the dead will give life to your mortal bodies also, through his Spirit that dwells in you” (Romans 8:11). Being raised from the dead — body and soul — to dwell with God in Heaven is the point of the Spirit being sent to us. That’s what we celebrate on Pentecost and that’s what makes us Christian.

I pray on this Pentecost that Catholics will be shocked out of their lukewarm tendencies, their acedia that keeps them comfortable in their jobs and money and little material triumphs. We must truly let the Spirit that has soaked our souls in our baptisms and confirmations to open our mouths to proclaim with the Apostles that Jesus Christ is the Way that all humanity has been given to share in God’s eternal glory.