Wednesday of the Fifth Week of Lent: Daniel 3:14-20, 91-92, 95, John 8:31-42.

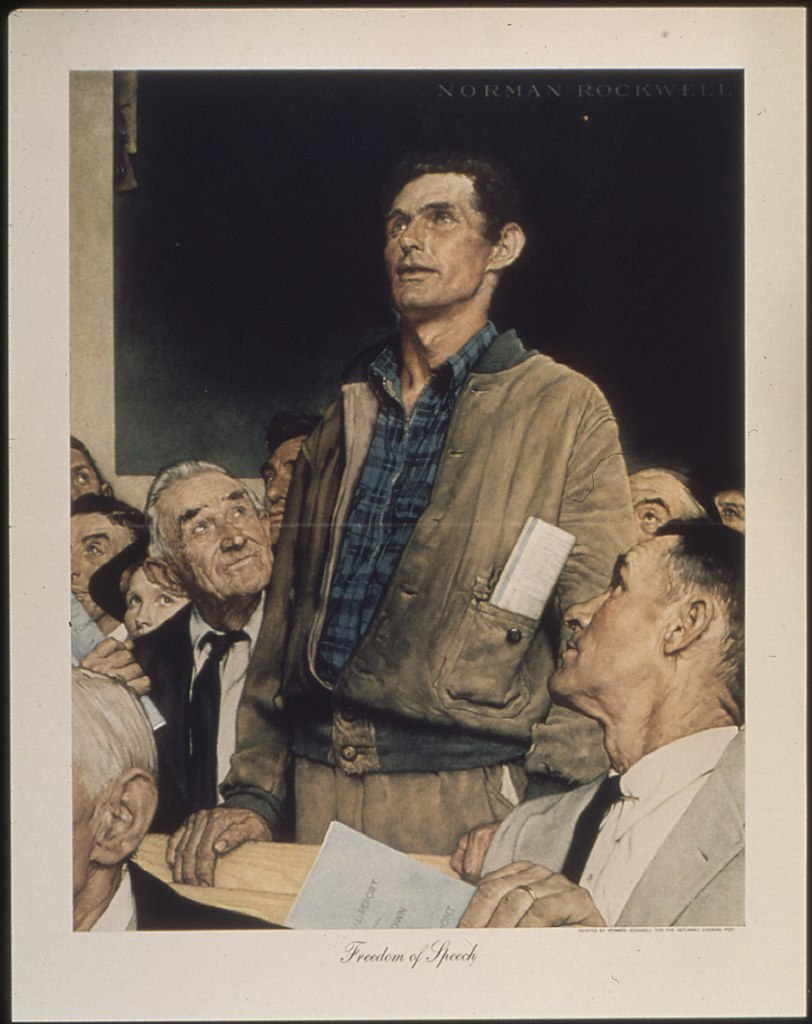

Ah, freedom, a major aspect of today’s gospel reading. Who knows more about freedom than the American (so we tell ourselves)? There was an article in one of our local news outlets, the Deseret News, just before the November 2020 presidential election that shed a lot of light on how Americans have thrown their notions of the constitution, the symbol of the flag, and personal freedoms into a blender to arrive at a specific brand of in-your-face freedom. The article is called Big Flags on Big Trucks, and details the phenomenon of “caravanning as a conservative way of protesting,” including a 6-mile-long train of trucks and cars flying flags and pro-Trump propaganda that drove the 380-mile length of Utah’s I-15 in late October, 2020. People’s political persuasions are not my concern with this site. A quote from this article, though, reveals something about how all Americans have twisted the concept of freedom to mean the opposite of what Christ means. “Liberals are always in your face. They want to push their opinion on you,” says a 22-year-old construction worker quoted in the article, “I have freedom of speech. I can say what I feel too.” Indeed, on both sides of the political spectrum, freedom means the unfiltered, unregulated firehose of opinion. Because American “freedom” implies the lack of any check or law, it has instilled a type of anarchy in the national psyche. It’s not too much of a leap to claim that Americans still have a bit of the wild West in them, feeling like they have the right to take matters into their own hands — certainly with words, but also with actions, guns, whatever. Our concept of freedom as empowering us to “say what I feel” or “do as I please” means that we envision ourselves as mini deities, marching about the world according to rules that we make up for ourselves, or no rules at all.

It’s important to state that this is a new (and errant) way of thinking about freedom. Human civilizations until the last several hundred years regularly had enslavement and servitude as part of cultures around the world. When someone was freed from slavery, this meant they could operate in society as any other citizen — according to the laws and prescriptions of the society. Free citizens certainly enjoyed more rights than slaves, but no one was exempt from the law except the rulers, and even then certain codes of conduct were expected. Americans founded their society on revolution from a colonial master, and the rhetoric of freedom has always enjoyed center stage. “Freedom” as a national touchstone grew with our abolishment of slavery after the Civil War (something that lagged behind European countries, by the way), and enfranchisement of women and people of color in the 20th century. I would claim that the civil freedoms we enjoy are not that different from many, if not most, other countries around the world, but in our minds, we are exceptional. Much has been written about American exceptionalism in academic circles, and suffice it to say here that our exceptionalism has many levels: we feel exempt from many prescriptions that other cultures have but also more exceptional in character, in the fiber of who we are, which results in a ton of entitlement. I don’t think any of us intentionally feels this way — it’s simply something that we take on by millions of subtle and not-so-subtle messages in our public discourse, our entertainment, our advertising, etc. We’ve seen increasingly savvy political preying upon this aspect of our national character, but that’s another post for another time.

In my mind, the consequence of American exceptionalism as a part of our national character is that we are weaker, more arrogant, and less conformed to Christ. More bluntly, personal or national exceptionalism is a form of sin, where we place ourselves above others. As children of God, equal to all other children of God, we are lying to ourselves when we imagine a type of exceptionalism. As Dostoevsky wrote, “People who lie to themselves and listen to their own lie come to such a pass that they cannot distinguish the truth within them, or around them, and so lose all respect for themselves and for others. And having no respect, they cease to love, and in order to occupy and distract themselves without love they give way to passions and to coarse pleasures, and sink to bestiality in their vices, all from continual lying to others and to themselves.” (The Brothers Karamazov, II, 2). Dostoevsky rightly locates the loss of truth as a crucial part of the spiral of sin.

Christ speaks today of the role of truth in establishing true freedom: “If you remain in my word, you will truly be my disciples, and you will know the truth, and the truth will set you free.” Christ promises freedom, but at the end of a sequence of things that starts with a personal journey with Him. Let’s start with the beginning: “If you remain in my word.” His word is both the teaching of the man Jesus as well as the Word of God contained in all of scripture. Jesus is affirming the laws and prescriptions of how to act and comport oneself as laid down for millennia in the scriptures as well as His own perfection of the law as He reveals during His ministry. Remaining in His word is where we start. Many (or most) of us may spend our entire lives just trying to get here, aspiring to remain, not slip, to train ourselves to resist worldly temptations, to pray often to the Father, to serve our fellow human like Christ.

Christ promises that if we remain in His word, we will truly be His disciples. This means we will have a personal relationship with our teacher. Our lives become more than just following rules of behavior. We are immersed in a spiritual relationship that feeds us and transforms us. It is dynamic. We learn from Him and lean on Him and He rejoices with us when we succeed in turning to goodness and away from evil. He also comforts us when we slip. As we check in with ourselves on this journey, we can start to see that we are living a fuller, denser life, allowing ourselves to be conformed to something divine, to take on a spiritual dimension that promises to be more meaty than our physical one.

Then Jesus promises us that we “will know the truth.” After remaining in His word and developing a personal relationship with our teacher, we will know the truth. Let’s pause here and say that anyone who thinks that truth is a matter of context or is subjective depending on who you are, well, this person cannot call herself a Christian. Jesus clearly here and elsewhere tells us that there is a (singular) truth — that truth lives in God and we apprehend it through Christ as the Way. In fact, this is how He can say, “I am the Way, the Truth, and the Light.” To deny that there is truth is at the heart of atheism. Thus, Nietzsche says, “What is the truth, but a lie agreed upon.” In this world of Nietzsche, nothing exists but people making things up and calling them “rational” or “true” or “false.” Apart from this being simply counter to everything God has revealed about reality, I find it quite a mental stretch, like a bad dystopian movie or an episode of the Twilight Zone. There are too many things that exist beyond us and to which we respond to limit the world in this way. Certainly, in God’s great created universe we can find amazement and life that surprises us, that we do not create. But even in what we do create, like artwork, there is something about beauty that speaks to something transcendent, something that carries meaning outside of what we determine it should be. Thus, even the cynical, anti-Christian, existentialist student of Nietzsche, Albert Camus, writes, “Fiction is the lie through which we tell the truth.” He affirms that there is truth, and that we tell ourselves fictions, some of which reveal the truth that is external to what we can create on our own.

Pope Francis does a lovely job of summarizing how Christianity conveys a denser, more profound understanding of truth:

In Christianity, truth is not just a conceptual reality that regards how we judge things, defining them as true or false. The truth is not just bringing to light things that are concealed, “revealing reality”, as the ancient Greek term aletheia (from a-lethès, “not hidden”) might lead us to believe. Truth involves our whole life. In the Bible, it carries with it the sense of support, solidity, and trust, as implied by the root ‘aman, the source of our liturgical expression Amen. Truth is something you can lean on, so as not to fall. In this relational sense, the only truly reliable and trustworthy One – the One on whom we can count – is the living God. Hence, Jesus can say: “I am the truth” (Jn 14:6). We discover and rediscover the truth when we experience it within ourselves in the loyalty and trustworthiness of the One who loves us. This alone can liberate us: “The truth will set you free” (Jn 8:32).

-from Pope Francis’s message on World Communications Day, January 24, 2018.

So, truth necessarily involves the “only truly reliable and trustworthy One,” God. It is only in our lifelong walk with Christ, within the fabric of that personal relationship where He transforms us into better and better human beings, that we start to recognize and discover truth.

Thus we arrive at the final part of this complex relationship and promise from Christ: “the truth will set you free.” We will get to the “free from what?” question presently, but first let’s linger on the fact that freedom comes as a result of a lifelong walk on the Way to the Kingdom where we discover truth “in the loyalty and trustworthiness of the One who loves us.” Contrast this complex, experiential definition with the American concept of freedom (“say what I feel” or “do as I please”). How self-centered and shallow it is revealed to be! There is no discovery of truth that underlies this type of “freedom”; everything comes from within our flawed selves. This is, in fact, the very definition of living in a state of sin and without God in our hearts. It’s hard to think of a saint who hasn’t warned us about allowing ourselves to be led by our passions and desires. St. Benedict: “No one should follow what he considers to be good for himself, but rather what seems good for another.” St. Alphonso Liguori: “He who trusts in himself is lost. He who trusts in God can do all things.” (We could go on and on). The point is that when we follow our own desires, we are being ruled by the prince of this world. This is how Satan works in us, by having us elevate our own interests above everything else. The Ten Commandments were given to us to help us push back on these desires and temptations — coveting property and people, disrespecting our parents, destroying people who stand in our way, and putting ourselves ahead of God. Sinning is giving into the unchecked desires of self that are not conformed to God.

(NB., desire can be good, too! Desire for God, sexual desire for a spouse, desire to have someone else do well or be saved from suffering, etc.)

So when Christ speaks of being set free, of course, He is saying, “everyone who commits sin is a slave of sin.” The slavery of sin is what He has come to free us from. Imagine if we lived in a land where people proudly spoke of their freedom and instead of the right to bear arms, to say whatever they pleased, or to hold private property they meant freedom from sin. Now, that would be a country to be proud to be a part of!

Along these lines, imagine if we found our purpose in this density of being, this filling out of ourselves with meaning and truth. Rather than pursing the goal of proving our worth by showing off accomplishments that we’ve done all on our own, as if our own merit is the driving force in our lives, what if we pursue the goal of being shown truth and goodness from outside of ourselves, by God. The first is a lonely, selfish, and ultimately shallow existence. The second is filled with the life of the heavenly hosts, it’s expansive, and it’s an ultimately deep existence.

We must close with St. Paul because we have to realize that Jesus gave us our freedom from sin permanently and irrevocably. While it continues to be our challenge and call to find truth after a lifelong personal walk with Christ, He permanently changed our ontological spiritual state with His death and resurrection.

Do you not know that all of us who have been baptized into Christ Jesus were baptized into his death? Therefore we have been buried with him by baptism into death, so that, just as Christ was raised from the dead by the glory of the Father, so we too might walk in newness of life. For if we have been united with him in a death like his, we will certainly be united with him in a resurrection like his. We know that our old self was crucified with him so that the body of sin might be destroyed, and we might no longer be enslaved to sin. For whoever has died is freed from sin. But if we have died with Christ, we believe that we will also live with him. We know that Christ, being raised from the dead, will never die again; death no longer has dominion over him. The death he died, he died to sin, once for all; but the life he lives, he lives to God. So you also must consider yourselves dead to sin and alive to God in Christ Jesus. Therefore, do not let sin exercise dominion in your mortal bodies, to make you obey their passions. (Romans 6:3-12).