Saturday in the Second Week of Lent: Micah 7:14-15, 18-20, Luke 15:1-3, 11-32.

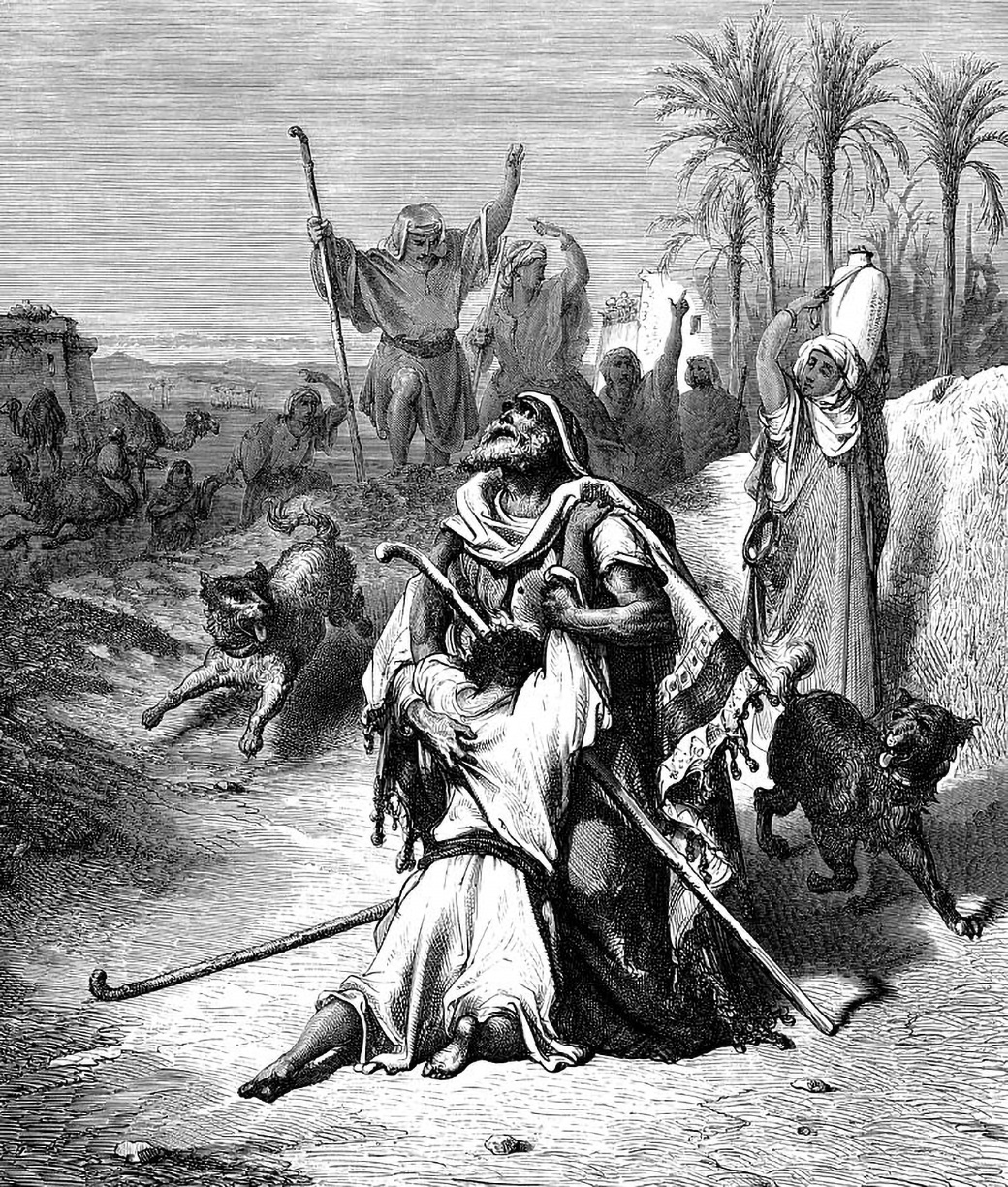

Today we read one of Jesus’s most famous parables, the Parable of the Prodigal Son. There is so much to say about it. The broad strokes: it displays the unflagging love of the father (that is, God the Father) and our ability to return to Him like the prodigal son, no matter how grievous our sins. The reflection below was originally posted last Lent – my primary excuse is that I’m very busy doing renovation work on my home today, but after I re-read this below, I thought it might be worth sharing again. So, let’s take a deep dive into the parable, especially the type of love the father provides.

We might not quite comprehend just how insulting the younger son is when he demands his inheritance. It would have shocked the Jewish audience to hear that the younger son demands a portion of the inheritance (the eldest son has first dibs and the younger is expected to work). When we look at the original Greek, we see that Jesus actually presents a deeper meaning here. When the son says, “Father, give me the share of your estate that should come to me,” the word Jesus uses for “estate” is οὐσίας (ousias), which means being, meaning, or essence. The son is asking for his inheritance, yes, but more literally the essence of the father. The prophets have a long tradition of referring to the inheritance of the nation of Israel (when they live by God’s precepts) as God’s grace and more specifically the nation’s glory and lands. Thus, it makes sense that the listeners to Jesus’s parable would understand an inheritance to have a double meaning of property/estate as well as the grace or essence of the father.

But Jesus speaks of the Kingdom of God throughout his ministry in a new, eschatological way. That is, inheritance means everlasting life with God in heaven (not just glory and land). The next sentence is a lovely way for Jesus to expand the meaning of the essence of the inheritance in the new Christology. I like to think of him saying it slowly and deliberately to his audience, making strong eye contact: “So he divided his property between them.” The reason this is so important is that he switches from ousias when describing the property/inheritance and uses βίον (bion, the singular form of bios), which means life. So, he gave them his life in response for the son’s demand for his portion of the inheritance. How deeply prophetic and significant to put this into the parable!

Today, we know how God gave his essence, his life, in the form of his only-begotten Son on the cross. This inheritance of which Christ speaks is love.

Knowing the type of inheritance given to the younger son, it is all the more shocking to hear that he used the essence of God given to him on a “life of dissipation” (i.e., prostitution, drunkenness, debauchery). He falls so far that he tends the Jew’s forbidden animal to eat, the pig. This places him in the lowest levels of uncleanliness for a Jewish culture obsessive about cleanliness in body and spirit.

Then we get to the younger son’s great conversion, which begins with a simple assessment of his own pathetic situation, as it does for most of us. His initial motivation is selfish, simply to get fed and earn some money, because selfishness is all he has and all he knows. But contemplation of his father, enkindled by the never-dormant ember of the essence of the Father given to him, broadens and deepens the return he plans. He commits to say, “Father, I have sinned against heaven and against you. I no longer deserve to be called your son; treat me as you would treat one of your hired workers.” The selfishness, in its destitution, finds something outside of itself to cling to: the Father, in front of whom the debasement of his sins is clear and undeniable.

At this point, we can turn to our great Doctor of the Church, St. Thomas Aquinas, who wrote extensively about the going from God (exitus) and returning to Him (reditus). He and other theologians understand God as the First Cause of all things and the End to which all things come. He writes early in his scholastic career: “[Sacred] doctrine will consider things in so far as they leave God at the start, and in so far as they are brought back to Him in the end. Thus, we understand divine things first as going forth [exitum] and, second, as returning to [reditum] the End.”¹ The Parable of the Prodigal Son concisely delivers to us this theology of our existence as ordered by God; the younger son goes forth from God and returns to Him. But, let’s order things precisely: first, the Father gives the son his essence to enable him to leave. This could be seen as the breath of God in our creation as well as every gift and grace of God given freely to us, such as Baptism.

What happens after the gifts are bestowed on us? This is another great generosity of our Lord: we have the free will to do with these gifts as we please. God tries throughout our history to instruct us on good uses of our free will, He gives us endless opportunities to use his inheritance for good works, He works to purify us, and has even poured out the love of the Trinity in the liturgy as a way for us to have true communion with Him. What is our personal story of reditus? I believe that this is what defines us as individuals: how we find our way back to God time and again, the decisions we make and the people we interact with on our way to God as the Truth and the End. It’s not the clothes we wear, the haircuts we have, the house we live in, the careers we strive for — in short, all of the things our secular society says define us. No the “person” who is hopefully granted everlasting life in the Kingdom is the being that worked with the essence of God that was bestowed on him or her; all the rest will be stripped away in death, for it is our spirit, our soul, that rests in God.

Let’s turn to the elder son and see ourselves in him. Whenever we feel like we’re on the right track, we’re honoring God and doing his will in the world, we may slip into the persona of the elder son, pathetic creatures that we are. Upon hearing that his father is throwing a feast to welcome home his prodigal son, the elder son becomes angry, refuses to enter the house, and is overcome with righteous indignation. In short, he is undergoing his own exitus, a leaving of God. What we see in him is the lesson Jesus has for the Pharisees and scribes who grumble and say a few verses before today’s reading, “This fellow welcomes sinners and eats with them.” Like the Pharisees, the elder son seems to have done everything correctly, or at least he’s done externally what was expected of him as a good son. Yet in his refusal to enter the house (the temple, the house of God), and his righteous indignation, we see that he never converted his heart to God. He has wasted his inheritance as much as the younger son, wasting it on his own sense of righteousness and fastidiousness about the law without digging deeper and truly letting the essence of the Father inhabit him.

The father immediately wants the elder son to participate in the welcome feast as well. The father seems to not sympathize with the elder son’s jealousy. I think this is a significant point. If we live with the Father and do His will, we are filled with the same love that He has. Our hearts are in unity with His. We should want the best for everyone and not be thinking of others as competitors to ourselves, for the love of God is not in finite supply — there is plenty for all. The father’s last gentle words of comfort to his son make me want to hide my head in shame for the elder son: “Son, you are always with me, and all that is mine is yours.” You can almost hear a note of puzzlement in the voice of the father at this reminder, as if the son should be aware of this if he has been a good son all these years. And it is here, in these tests of our faith and fidelity of heart, that God finds out if we are good inheritors and produce good fruits (to echo the language from yesterday’s reflection, Tend to the Good Fruit of the Vineyard).

It is interesting to note that the Greek verb used when the father “pleaded” with his elder son to stay is παρεκάλει (parekalai), which is the same root as the name given to the Holy Spirit: παράκλητος (parakletos), or paraclete. “Paraclete” carries a complex meaning for the apostles, as the Holy Spirit advocates, witnesses, comforts, and intercedes. The father in our parable is acting with the Holy Spirit, and indeed, this is how God works within us here on earth. The Holy Spirit was promised by Jesus: “And I will ask the Father, and he will give you another advocate [Παράκλητον (Parakleton)] to help you and be with you forever— the Spirit of truth. The world cannot accept him, because it neither sees him nor knows him. But you know him, for he lives with you and will be in you” (Jn 14:16-17). We see the author of Luke’s gospel use this same verb, parekalai, three times in the Acts of the Apostles in a similar way. The first one is striking because it is attributed to St. Peter directly after the Holy Spirit descends at Pentecost and they leave the upper room speaking in tongues. Peter addresses the crowd that gathers with a long speech and then “he testified with many other arguments and exhorted [παρεκάλει (parekalai)] them, saying, ‘Save yourselves from this corrupt generation'” (Acts 2:40). Thereupon, three thousand were converted to Christianity that day. This is a clear indication that the author uses the word to mean the action of the Holy Spirit within us as we exhort, plead, encourage, implore others to convert to God. It is another gift we barely realize that we have from God, the gift of the Holy Spirit active within us as we exhort and encourage others.

The parable ends with a final window into the vast love of the Father: “now we must celebrate and rejoice, because your brother was dead and has come to life again; he was lost and has been found.” I love passages from scripture that remind us that God rejoices, that he wants to be delighted. And here we see that he fundamentally delights in each of us on our path of reditus. Our return to Him is the most pleasing thing we can do. And once we are with Him, we need not desire more personal doting, because we can join with Him in welcoming others as they find their ways back to Him, too.

¹ The translation of the Latin here is partially my own. The original text: “consideratio hujus doctrinae erit de rebus secundum quod exeunt a Deo ut a principio, et secundum quod referuntur in ipsum ut in finem. Unde in prima parte déterminât de rebus divinis secundum exitum a principio; in secunda secundum reditum in finem” (I Sent., 2 dist., divisio textus).