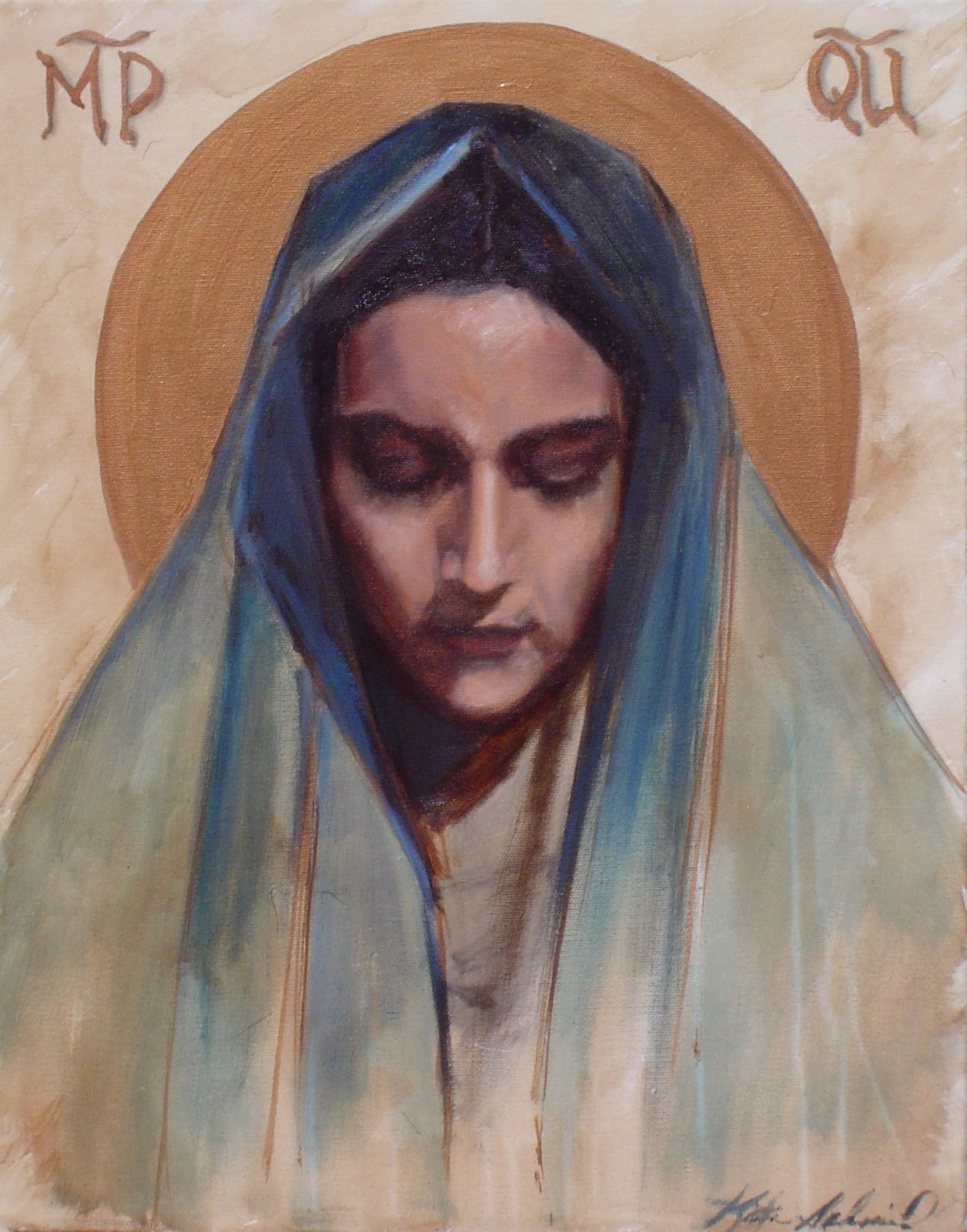

Solemnity of the Immaculate Conception, Tuesday in the 2nd Week of Advent: Genesis 3:9-15, 20, Ephesians 1:3-6, 11-12, Luke 1: 26-38.

Today the Roman Catholic Church celebrates the Solemnity of the Immaculate Conception in a more codified manner than any other Christian denomination, including our Orthodox brethren. The story is long, essentially going back to St. Augustine’s position on original sin carried by humanity, inherited from Adam and Eve (and, interestingly, passed on genetically through male semen). A feast day honoring Mary — specifically her birth into a sinless state — actually began in the Eastern Orthodox churches in the 600s. Four hundred years later, we have records of theological objections in the Western church. Nonetheless, it was the Roman Catholic Church that ended up embracing this tradition and, in 1854, Pope Pious IX invoked papal infallibility to declare as dogma that Mary, through God’s grace, was conceived free from the stain of original sin. Protestants outright rejected this dogma as false and the Orthodox Churches did not accept the teaching as dogmatic (they never accepted St. Augustine’s teaching on original sin, for that matter). The objections were that there was no textual evidence in the New Testament to support this teaching, but Pope Pious had the support of 90% of his bishops on the matter and thus issued the papal bull Ineffabilis Deus.

I don’t want to challenge or defend the Roman Catholic dogma of Mary’s own Immaculate Conception — this is far outside of my knowledge and I have no right or desire to weigh in on this. Instead, I’d like to ponder the realities that the Eastern and Western Catholic Churches share in their reverence of Mary. Today’s readings re-introduce us to humanity’s original sin in the story of Adam and Eve in the Book of Genesis. This is because we consider Mary to be the new Eve. This belief of the Church arose in the earliest years, during the Apostolic Age and Age of the Church Fathers. Justin Martyr, born in 100 AD, was first trained as a Stoic philosopher, then adopted Platonism before converting to Christianity after a conversation with an old Christian man. His logical, philosophical argumentation style has given us invaluable records about the early Christians. He writes of the new Eve,

He became man by the Virgin, in order that the disobedience which proceeded from the serpent might receive its destruction in the same manner in which it derived its origin. For Eve, who was a virgin and undefiled, having conceived the word of the serpent, brought forth disobedience and death. But the Virgin Mary received faith and joy, when the angel Gabriel announced the good tidings to her … she replied, ‘Be it unto me according to your word.’

(Dialogue with Trypho, Ch 100).

Let’s take note of how he draws the parallel between Eve and Mary along the lines of disobedience and obedience, specifically in whose word they listen to. Eve receives and obeys the word of the serpent, which is identified with worldliness, guile, and the Devil. In so doing, she disobeys the Word of God. Mary, on the other hand, receives and obeys the Word of God on multiple levels: the Word via the mouth of the Angel Gabriel and the Word made flesh in her womb. So she atones for original sin by making the correct choice of obedience (an internal act of reception and obedience) and also she assents to become the living vessel for a new humanity, perfected by God (an external act of procreation, a sharing in the creative energies of God).

Here we start to see the importance of both Eve and Mary being virgins: they are pure vessels, starting points for what is to come. Because of her disobedience and fall from the garden, Eve gave birth to sin and degradation in the very first generation (Cain and Abel). Thanks to her obedience, Mary is a fitting vessel for God’s perfecting creative energy, and she gives birth to the Messiah, Jesus Christ. Eve starts a history of fallen humanity, subject to sin, while Mary begins a history of a new people, adopted sons and daughters of God the Father who are given the chance for sanctification and deification in their lives.

Viewed in this way, it is fitting to mark with a Solemnity this perfect human who received God’s Word willingly and completely, thus ushering in an entirely new era for humanity.

We must, of course, revere Mary as the Queen of Heaven and blessed saint that she is, but also recognize that hers was the work to which all Christians are called: reception of God’s Word and doing His Will. It is always God who is the author, and we are but clay in His hands, even Mary. Another Church Father, Tertullian (c.150-240 AD), writes about the importance of Mary’s assent in terms of salvation history and a new humanity. “He who was going to consecrate a new order of birth, must Himself be born after a novel fashion,” (On the Flesh of Christ, 17). Tertullian recalls how, in Genesis, Adam “was formed by God into a quickening spirit out of the ground — in other words, out of a flesh which was unstained as yet by any human generation.” The virgin in this case is the earth herself (rather than Eve). Tertullian sees an interesting phenomenon in the way God chooses to rectify Eve’s original sin:

it was by just the contrary operation that God recovered His own image and likeness, of which He had been robbed by the devil. For it was while Eve was yet a virgin, that the ensnaring word had crept into her ear which was to build the edifice of death. Into a virgin’s soul, in like manner, must be introduced that Word of God which was to raise the fabric of life. … Hence it was necessary that Christ should come forth for the salvation of man, in that condition of flesh into which man had entered ever since his condemnation. (17)

In other words, the first “operation” is that God forms a “quickening spirit” out of the virgin ground, but the “contrary operation” is the Word of God introduced into the soul of the Virgin Mary. In the first, there’s a body (the earth) from which God creates a spirit (Adam). In the second, there’s a spirit (Mary) from which God creates a man (Jesus). The Word of God is the creative energy for both.

I am struck in Tertullian’s writing by how intertwined we find God and humanity as well as bodies and souls. In particular, I like how he describes the Incarnation as a the way “God recovered His own image and likeness, of which He had been robbed by the devil.” This is a fantastic reminder that we are, fundamentally and ultimately, God’s own image and likeness. No matter how much we like to think that we are our own beings, we are His. Mary recognized this and gave us back to Him. Thus, we can understand St. Paul’s words to the Ephesians in today’s second reading: “he chose us in him, before the foundation of the world, to be holy and without blemish before him.” We can’t forget that God made us to be holy and without blemish before him. This is our driving motivation behind all moral behavior: to please our Creator and rise up to His dreams for us. As He loves us, so we strive to love Him. Paul explains that Christ’s existence, sacrifice and resurrection makes our unification with our Father possible, “In him we were also chosen, destined in accord with the purpose of the One who accomplishes all things according to the intention of his will, so that we might exist for the praise of his glory, we who first hoped in Christ.” Our existence — with God’s grace — can be the “praise of his glory.”

And is this not what Mary’s existence is? Through her, we learn our own potential. We learn that we can assent to God’s will and bear in ourselves the action of the Holy Spirit, letting everything point to the fruits of the Spirit. This requires a lot of grace! We recognize this as the Angel Gabriel greets her in today’s gospel, “Hail, full of grace! The Lord is with you.” I examined the gospel of the Annunciation at length in my post Our Blessed Kecharitōmenē, but let me borrow a few passages here for emphasis. The original Greek is enlightening:

Ancient Greek: χαῖρε, κεχαριτωμένη, ὁ κύριος μετὰ σοῦ.

“Greeklish”: Chaire, kecharitōmenē, ho kyrios meta sou!

English: Hail, “Full of Grace,” the Lord is with you!

Kecharitōmenē is not an adjective; it’s used only once in sacred scripture and never in secular texts. It is a noun, a unique title for Mary, and would be better translated as “The One Whom Grace Inhabits.” Thus, a better translation of the whole greeting would be: “Grace to you, The One Whom Grace Inhabits, The Lord is with you!”

This is much grace indeed, and we can consider how many ways grace actually “inhabits” Mary. The point is that our relationship with God is always supported and nourished by Him. Even in this most unique and spectacular human, we see God’s grace doing a lot of heavy lifting. She must have courage, she must remain faithful to Him in her heart and actions, but she is not alone in this: “The Lord is with you!” Gabriel reiterates this when explaining how Elizabeth can bear a son in her old age: “for nothing will be impossible for God.” This reassurance from Gabriel enables Mary to respond, “Behold, I am the handmaid of the Lord. May it be done to me according to your word.” And with these words, she changes the world.

I guess my reflection has made me consider that even though Mary is so special and vastly above the rest of us in holiness, grace, and perfection, she is also very close to us. She is simply human, a vessel for God, just like us. We can revere her for who she is and what she accomplished by being completely open to God’s grace, and we can seek her understanding, comforting embrace when we struggle with the same smallness of being human in our times of weakness.