Monday – Wednesday in the 10th Week of Ordinary Time: 1 Kings 17-18, Matthew 5: 1-19.

The first three days of this week (see Monday, Tuesday, and Wednesday readings) give us consecutive readings from the first book of Kings in the Old Testament and the Sermon on the Mount from the gospel of St. Matthew. We have the story of Elijah’s God-imposed exile from the Israelites juxtaposed with the Beatitudes and Christ’s sayings about who He is and what we are called to be. There are many provocative connections between these texts, which, at first glance, we might not immediately identify with each other.

Let’s look at the Elijah story as a whole. Elijah is an important figure for at least three religions: Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. He was a prophet and miracle worker who displayed a zeal and devotion to God at a time when the Israelites had all but abandoned Him while adopting idolatrous faith in Ba’al and Asherah. The time period is 800 years before Christ, the Jewish state is split into the northern kingdom (Israel) and the southern kingdom (Judah, which contained Jerusalem). Elijah is a prophet in the northern kingdom and the King during his time was the absolutely awful King Ahab (let your next reading of Moby-Dick take on new significance). Ahab came after a series of bad kings starting with Jeroboam but scripture tells us “Ahab son of Omri did evil in the sight of the Lord more than all who were before him” (1 Kings 16:30), and again: “Ahab did more to provoke the anger of the Lord, the God of Israel, than had all the kings of Israel who were before him” (1 Kings 16:33). Part of the problem was his wife, Jezebel, a Phoenician princess who was undoubtedly a strong political match that helped stabilize Israel in the region. Ahab allows Jezebel to erect statues and temples to the Canaanite god Baʿal and the goddess Asherah. She does such a thorough job that she nearly exterminates the priests and prophets of the Jewish God (except the ones who hide in mountain caves) and brings in hundreds of her own prophets to Baʿal. The northern kingdom of Israel seems to have no state support for Yahweh, and the people fall into idolatry. Even the accursed city of Jericho — the first city to fall under Joshua’s entrance into the Promised Land after the Jews had wandered in the desert for 40 years with Moses — is rebuilt under King Ahab’s rule despite the curse Joshua had laid upon it if it were rebuilt (which comes true).

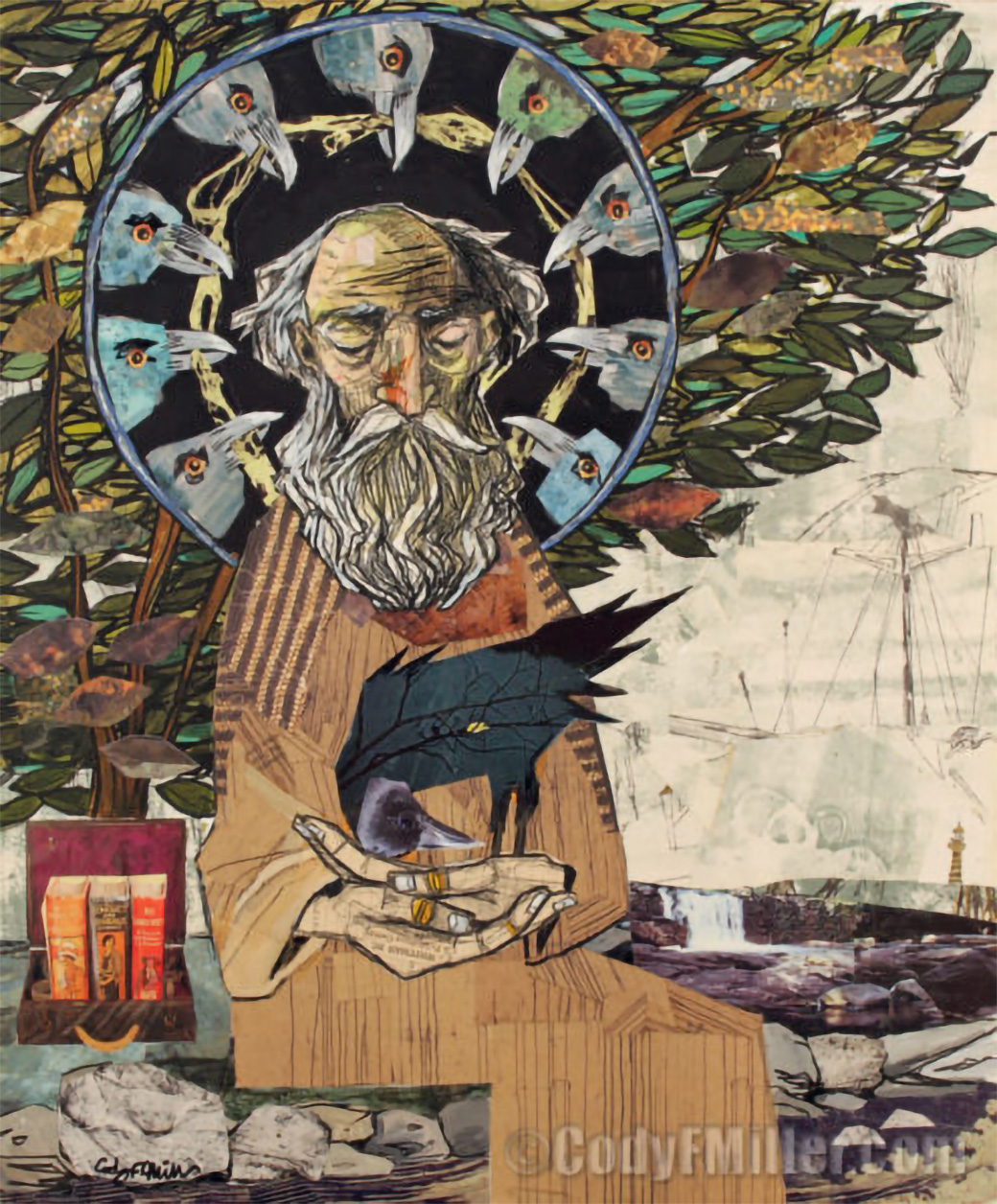

As we see over and over in our salvation history, God intervenes on behalf of His Chosen People through his anointed prophets. The Israelites have brought a disastrous drought upon themselves due to their unrepentant idolatry and Elijah tells King Ahab, “there shall be neither dew nor rain these years, except by my word” (1 Kings 17:1). The Word of God tells Elijah to go east of the boundary of Israel, the Jordan river, to “Wadi Cherith.” A wadi is a feature of desert hydrogeology, a seasonal creek that does not have water year-round. They range from relatively flat areas to more wild, ravine-line gullies. “Cherith” is the English spelling of the Hebrew name כְּרִית “Kərīṯ”, which means cut off or separated — something Elijah is being asked to do — it also means “carved” or “gorge,” which suggests that this was one of the more wild wadis, probably good for hiding from an angry king. The Word tells Elijah, “You shall drink from the wadi, and I have commanded the ravens to feed you there” (1 Kings 17:4). What makes this interesting is that the raven was among the birds the Jews were told to consider “detestable.” In Leviticus, we hear that the Lord tells Moses and Aaron that all ravens (among other birds and animals) “shall not be eaten; they are detestable” (Lev 11:13). Furthermore, “And by these you shall become unclean. Whoever touches their carcass shall be unclean until the evening, and whoever carries any part of their carcass shall wash his clothes and be unclean until the evening” (Lev 11:24-25). For this reason, God-fearing Jews would avoid ravens. Yet the ravens bring Elijah bread and meat in the morning and evening (thus he doesn’t eat them or necessary touch them), but the whole setup is definitely on the edge of being unclean from a strict Judaism standpoint.

But Elijah doesn’t bat an eye. He goes there as God commands until the wadi dries up. He accepts the water, bread, and meat provided by God. It reminds me of the vision Peter receives in the Acts of the Apostles when a great sheet from descends from heaven with all sorts of detestable creatures on it and God encourages him to eat, saying “What God has made clean, you must not call profane” (Acts 10:15). While Peter understood this as opening up restrictive purity laws as well as opening up the new Christian Church for Gentiles, his vision and the Elijah raven episode emphasize obedience and humility in the face of God’s will.

And here we have our first connection to the Sermon on the Mount. With the Beatitudes, Jesus reaffirms the type of human who is pleasing in God’s eyes, and it has everything to do with humility, obedience, and authenticity over appearances.

Entire books have been written on the Beatitudes, so I can’t do much justice here, but let’s think about what type of person Jesus describes as being “blessed.” These are his words: the poor in spirit, they who mourn, the meek, they who hunger and thirst for righteousness, the merciful, the clean of heart, the peacemakers, they who are persecuted for the sake of righteousness. This is not a picture of the proud and strong, of those in power or even those in control of what happens to them. The “clean of heart,” in particular, gets after the type of purity that God desires. The extensive rules given to Moses are meant to create a person who is dedicated absolutely to God, who will follow His prescriptions over his or her own desires and pleasures. The purity laws help to remind the Jews that their goal is to purify themselves specifically for the Lord, not as bragging rights over their neighbors or as cause to visibly separate themselves from other humans. The purity laws are meant for Jews to take seriously the idea of cleaning out the evil from their lives and becoming truly pure internally, that is, “clean of heart.”

This is an important point. I’ve heard my fellow Christians (and Jewish friends) scoff at the crazy list of unclean and impure things in the Jewish tradition. Orthodox Jews are seen as going way overboard. I don’t pretend to be able to parse out the differences between what’s impure and what’s allowed (nor to know when someone is fetishizing the idea of worldly impurity as an affectation of character rather than a true devotion to God), but this act is very much solidly within the Christian tradition, too. Consider Lent, when we forgo pleasures and seek to purify our hearts through prayer, penance, self-denial, and repentance for our sins as we prepare for Easter. Consider the lives of monastic communities, some of whom live in silence, many of which regularly observe fasts or have restricted diets. And how about the mortification of the flesh?? This isn’t some bygone practice done by masochistic medieval saints; it’s come to light that Pope St. John Paul II practiced mortification of the flesh. The National Catholic Reporter states, “Msgr. Slawomir Oder, postulator of the late pope’s cause [for canonization], said Pope John Paul used self-mortification ‘both to affirm the primacy of God and as an instrument for perfecting himself'” (Pope John Paul practiced self-mortification, Jan 10, 2010). All of these Christian practices align with the same motives of the Jewish purity laws: to create a clean heart, a devotion to God, a reminder that the flesh is weak and the world should not be the object of our attachment or desire. Together with the Jews, we share a belief that sin, evil, and Satan (the tempter) are real aspects of our life in the world and that we must guard against aligning ourselves with the devil.

This is a good time to reflect on Wednesday’s gospel reading, a continuation of the Sermon on the Mount in St. Matthew’s account, when Jesus proclaims, “Do not think that I have come to abolish the law or the prophets. I have come not to abolish but to fulfill.” We Christians are a continuation and fulfillment of Judaism. We pervert and misunderstand Christ if we imagine ourselves outside of the Jewish tradition. He very clearly states that He is not starting something new or breaking with God’s revelation to humanity for the preceding thousands of years. While not starting something new, He absolutely brings something new to us: divinity dwelling as man on the earth and His sacrifice of Himself for the salvation of humanity. But He is continuing, perfecting, and fulfilling God’s promise to humanity, not starting fresh. Jesus is insistent on this point, always pointing back to the Jewish patriarchs, couching His actions in the prophecies of Jewish prophets, and speaking the Word of God that His own divine nature shared with these people over the previous millennia.

On this point, let’s return to Elijah, with whom Jesus’s divine nature, the Word of God, was present. After the water in the wadi dries up, God tells Elijah, “Move on to Zarephath of Sidon and stay there. I have designated a widow there to provide for you.” So God continues to care for Elijah as an exile from Israel, hidden now in a Phoenecian city. But watch what God does here through Elijah. When Elijah meets the widow, she is about to make her last meal for herself and her son because they are destitute. Elijah asks for her to trust in the Lord who has told him, “The jar of flour shall not go empty, nor the jug of oil run dry, until the day when the LORD sends rain upon the earth.” The woman obeys Elijah, displays faith in the Lord and his prophet, and indeed the flour and oil replenish themselves and the three of them eat for a year. Despite the outward, slightly shameful appearance of an exiled Jew living with a widow in a Gentile city, this is the fundamental cycle of God’s saving work in humanity. First, He asks His chosen one to trust Him and bestows His grace when the chosen one obeys, especially in humble circumstances. Next, He asks that person to be an instrument of His will on the earth, bringing others to faith and under the grace of God. This is the core of our faith and salvation: hearing God’s call, trusting in Him, and bringing others to God’s light. These readings show this with Elijah, but scriptures also show this cycle with other prophets in their times and Christ in His time. We must realize that this is also true for us in our time.

This reading of Elijah and the widow of Zarephath occurred yesterday (Tuesday), and the accompanying gospel reading recounts Christ’s lesson directly following the Beatitudes where he tells his disciples that they are the salt of the earth and the light of the world. We can see how Christ’s words echo the life example Elijah sets: “Just so, your light must shine before others, that they may see your good deeds and glorify your heavenly Father.” This is the cycle in which we are called to participate, like Elijah and like Christ Himself. This is the meaning of life: to listen to the Father, become pure of heart and poor in spirit, let our faith shine in our deeds, and have our glorification of the Father draw others to God’s embrace.

These readings end with a note of finality today (Wednesday). After three years of drought, God tells Elijah: “Go, present yourself to Ahab; I will send rain on the earth” (1 Kings 18:1). When he meets Ahab, who calls him the “troubler of Israel,” he says: “have all Israel assemble for me at Mount Carmel, with the four hundred fifty prophets of Baal and the four hundred prophets of Asherah, who eat at Jezebel’s table” (1 Kings 18:19). Once the people are assembled, Elijah makes a very clear statement: “How long will you straddle the issue? If the LORD is God, follow him; if Baal, follow him.” Based on archaeological evidence of home shrines and figurines of gods like Asherah, scholars argue that polytheism was relatively normal among the Jewish people until after the Babylonian exile (605-539 BC). Elijah’s statement here supports this assertion; he sees devotion to many gods as not just inconsistent with the teaching that Yahweh is the only God, but downright heretical and needing to be stamped out. Simply put, if you follow our God, you can’t at the same time follow another.

So Elijah, at God’s instruction, announces the great sacrifice challenge. The hundreds of prophets for Baʿal can’t get their bull offering to ignite on their altar despite frenzied dancing, prayers, and self-laceration for hours. Before Elijah calls upon God to immolate his offering, he accomplishes a symbolic re-baptism of Israel in the faith by dousing the butchered bull, sticks, and altar in water three times (we can see the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit in God’s instructions here) until the trench around it is full. Elijah’s prayer to God over the offering ends with, “Answer me, that this people may know that you, LORD, are God and that you have brought them back to their senses.” On one hand, it seems incredible that the Jews would need more convincing or to be brought back to their senses after God so proved Himself to them through Abraham, Moses, Jacob, David, Solomon, and so many other early figures. But considering that the people had been ruled by weak and faithless kings in the northern kingdom for generations, I suppose it makes some sense. Still, I’m starting to feel Jesus when we hear Him say, “Unless you see signs and wonders you will not believe” (Jn 4:48).

God’s answer exhibits his totality: “The LORD’s fire came down and consumed the burnt offering, wood, stones, and dust, and it lapped up the water in the trench.” Vaporizing water, burning up stones and dust — signs that not a shred of doubt should be left in the minds of the Israelites. Indeed, they have the fear of God put back in them: “Seeing this, all the people fell prostrate and said, ‘The LORD is God! The LORD is God!'” But while the lectionary reading ends here, scriptures contain one more verse: “Elijah said to them, ‘Seize the prophets of Baal; do not let one of them escape.’ Then they seized them; and Elijah brought them down to the Wadi Kishon, and killed them there” (1 Kings 18:40). Sensitive modern readers might balk at this verse and wonder why such retribution is necessary. But we must not edit scriptures to fit our sensibilities and ideas of who God is. The totality of God includes judgment. Most of us do not experience judgment here on earth and we are taught that it is something that happens in the afterlife but that’s not saying God can’t exact judgment whenever He cares to. When offering His people a chance to come back to Him, when entering human history so directly through the lives of His prophets, God makes Himself present in ways that cannot exclude all parts of His totality. He is salvation for the just and devastation for the evil. There’s no way around this, it is His nature as being all pure, all good, the divine Lord. There is no room for anathema and evil in the presence of the divine love – it simply cannot exist together because then it would no longer be pure, divine love. We may prefer to concentrate on the loving salvation God offers us, and that’s fine, but we would be wrong if we thought that God did not bring terrible justice down on the evil among us.

And so we can better understand today’s gospel reading as well. Just like God’s divine totality uplifts the faithful and crushes the unfaithful, Jesus reminds us of the ultimate fate that awaits us: “Therefore, whoever breaks one of the least of these commandments and teaches others to do so will be called least in the Kingdom of heaven. But whoever obeys and teaches these commandments will be called greatest in the Kingdom of heaven.” Tying this all together, we can see that the great cycle of salvation in which we are called to participate has very real consequences. It’s not just to feel good or to torture ourselves with guilt in this world. These are eternal consequences and ones that should define us.

Pingback: God’s Voice: Quiet, Insistent, Uncompromising | Discerning Dominican