Friday in the Fifth Week of Lent: Jeremiah 20:10-13, John 10:31-42.

Today’s readings show the inexorable movement of Jesus’s ministry towards the Passion but also the irrefutable logic he provides in his works and words. The take-home message of the gospel narratives seems to be that since humanity can’t accept the divine truth brought into their midst, Jesus must be crucified as a sacrifice on our behalf, not just to fulfill prophecy, but as a very real atonement on our behalf for our rejection of Him, the Spirit, and the Father.

Jeremiah was a “repent, the end is near!” prophet. The Book of Jeremiah is so interesting in part because it is a first-hand account of someone we’d probably call a crazy person if we saw them on the street corner. In the verse prior to the ones in today’s reading, he explains that he tries not to be that guy and he knows he’s a “laughingstock,” but he can’t resist God’s message within him: “If I say, ‘I will not mention him, or speak any more in his name,’ then within me there is something like a burning fire shut up in my bones; I am weary with holding it in and I cannot” (Jer 20:9). He shares a clear insight into what it means to completely give yourself over to God: “O Lord, you have enticed me,” he says, “you have overpowered me” (Jer 20:7). This is a great example of how we can’t pigeonhole God into a single metaphor or image. He’s not always the benign guiding light or the patient beating heart of love. Sometimes He’s the urgent master, beguiling us with His energy and leading us to preach like wild people (or wear camel hair and eat grasshoppers and wild honey like St. John the Baptist).

So in today’s reading, Jeremiah laments that he is abandoned by his friends and trapped by his enemies, but he is aware that in a way he brought it upon himself. After all, he pointed out how wicked everyone was and how they would be conquered and enslaved. Not exactly words to win friends. At the beginning of this very chapter, the priest Pashhur beats him and puts him in the stocks for a day because he hears him prophesying. When he is let out, Jeremiah delivers a tirade complete with curse and death sentence for Pashhur. Firebrand, indeed. So we must read today’s lament within this mixed bag of emotions: a man who wants to save his people, but ends up being hated by them. When he tries to hold it in, he can’t resist God, whom he loves but also feels a bit exhausted by. He notes the inevitability that God will triumph over those persecuting him because He is “a mighty champion.” Jeremiah has cast his lot with the Lord over all else, and it’s interesting to hear the way he describes God. The lectionary reads at one point, “O LORD of hosts, you who test the just, who probe mind and heart,” and it seems like Jeremiah is speaking from experience, as one who has been tested in mind and heart. The NRSV Bible translation of this verse is “O LORD of hosts, you test the righteous, you see the heart and the mind; let me see your retribution upon them, for to you I have committed my cause,” and we hear even more clearly the internal dialogue Jeremiah is having with the Lord. He is saying, you’ve tested me, you know my heart and mind, so let me confess that I want to see your retribution on them, for I have long ago committed to you and you know that I am just a petty human doing your work.

The passage we read ends in a seemingly triumphant way: “Sing to the LORD, praise the LORD, For he has rescued the life of the poor from the power of the wicked!” And I don’t mean to question the legitimate praise and truth in this statement, but when we read the very next verse, omitted from today’s reading, we get quite a different picture of his struggle. He says, “Cursed be the day on which I was born!” (Jer 20:14) and a little later to clarify: “Why did I come forth from the womb to see toil and sorrow, and spend my days in shame?” (Jer 20:18). These are the words of a tortured soul. He knows on a certain level that he is but God’s tool in this life, yet he is also committed to and entranced by God. He knows that he is doing good work but also knows that the Lord has planned the destruction of Jerusalem and the Babylonian Exile for the Jews. Jeremiah teaches us that the life of the prophet is a hard, hard, thing. That God’s love sometimes carries a difficult message, one that will make you hated.

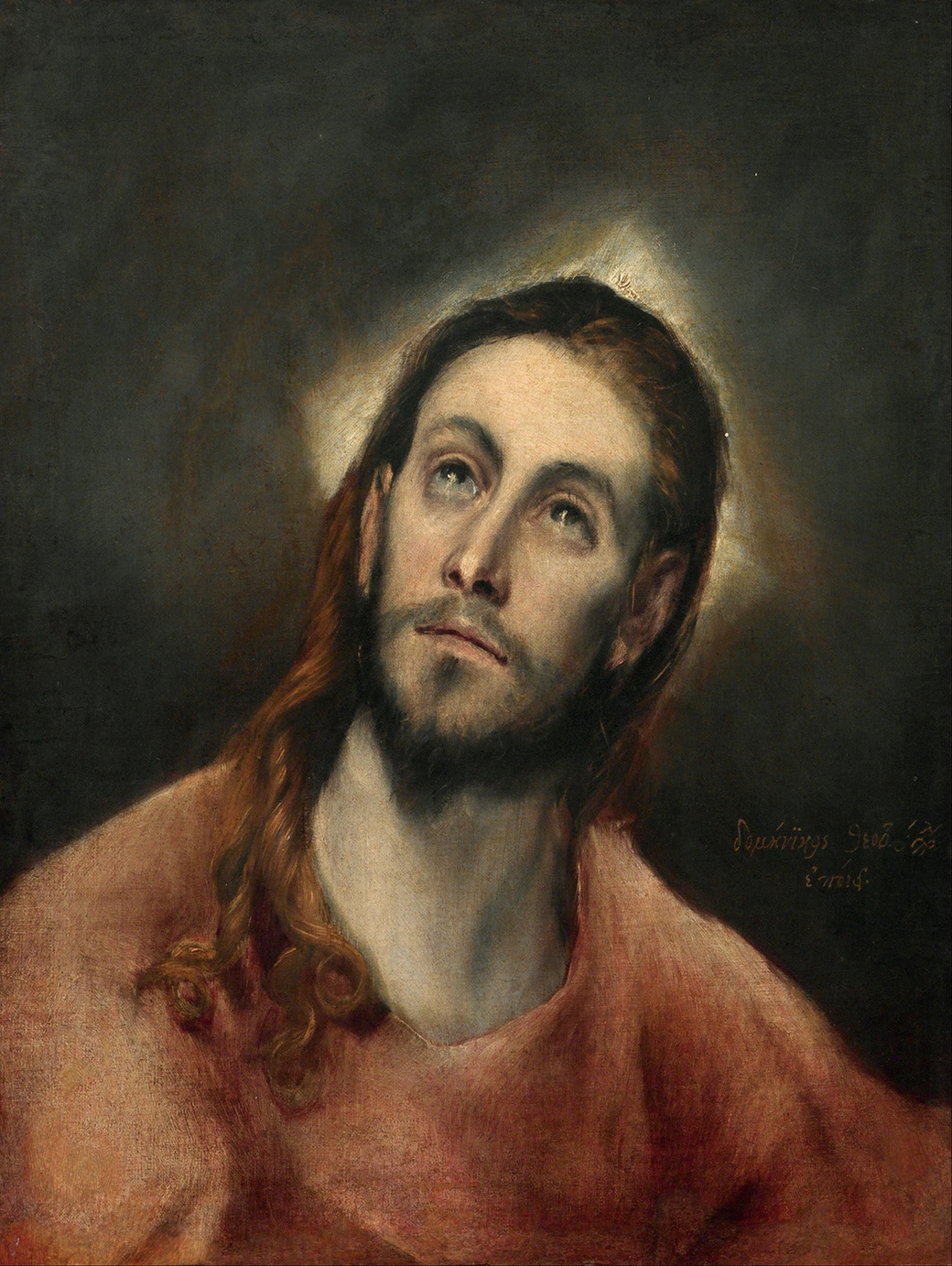

Which brings us to our greatest prophet and Only-Begotten Son of God, Jesus Christ. Much like Jeremiah, he faces some serious hatred and persecution, as the first line of today’s reading states, “The Jews picked up rocks to stone Jesus.” But Jesus handles Himself very differently than Jeremiah. We never get the sense in the gospels that he is mentally tortured, even when crying in the Garden of Gethsemene, or that He wishes to see the Lord’s retribution on the people. Exactly the opposite: He still wants to grant them salvation and forgive them, all the way to His death and triumphantly so with His Resurrection. This is the great game-changer in history. No mere human could do this. It is why God had to send us His Son and have Him take on the flesh of humanity so that He could enact such forgiveness and love when those of us who were merely human would have failed long before.

How can he accomplish this? The fact that he is the Logos of God has something to do with it. In today’s reading, he displays the irrefutable logic inherent in the Logos. Faced with stoning, He calmly asks, “I have shown you many good works from my Father. For which of these are you trying to stone me?” Logical point one: why would you stone a miracle worker? Point two: these good works have come from God the Father, why would you stone someone bringing you works from God?

They respond that it’s not the good works but his words, that “You, a man, are making yourself God.” He responds first by pointing out that God Himself in the Scriptures (in Psalm 82, to be precise) says “You are gods,” when he is speaking to the highest earthly authorities (judges, kings) to remind them of their moral responsibilities and the fact that they’re failing at giving justice to the weak and not the wicked. Jesus’s point is that if the Scriptures, the very Word of God, in fact, call some humans “gods,” especially when those were being called to the carpet for shirking their duties, then why is it blasphemy for him to call himself “Son of God” when he is enacting the works of the Father? His logic resides in the Scriptures, the Law itself. He goes on to let the works of the Father be his testimony:

If I do not perform my Father’s works, do not believe me;

but if I perform them, even if you do not believe me,

believe the works, so that you may realize and understand

that the Father is in me and I am in the Father.

In other words, if I perform no miracles, then you shouldn’t believe me. But look at these works of the Father and you can believe them even if you don’t believe me. Maybe through them, you’d realize and understand when I say I am the Son of God. His logic cannot be questioned. There is no arguing with it. They simply try to grab him. Our lectionary reads, “but he escaped from their power.” The Greek, however, is that he “went forth from” (ἐξῆλθεν / exēlthen) — interestingly, the same verb used to describe the water and blood that “flowed” from his side when he is pierced by a spear on the cross — “their grasp” (literally, their hands). This sense of “going forth” like flowing water reinforces the sense of irrefutability of the logic that we hear from the Logos of God. When water flows, we are somewhat at a loss of how to stop it, just like the Word of God can’t be stoppered and Jesus can’t be arrested before His time. These things are not subject to the will of humanity; they operate on a different plane and they are inevitable.

As we have read Jesus’s exchanges with the Jews in Jerusalem all week, I am struck by the repeated rejection He received and the unwillingness of the Jews to hear His message. There were many years when I only got the “greatest hits” readings on Sundays, often focused on his miracles and great sayings, and they don’t portray the fuller story of his work as a prophet who is rejected by his people. The gospels are definitely meant to be read as a narrative, straight through, beginning to end. The whole Bible for that matter, for how else can we see the redemption of Jeremiah in the figure of Christ, who experiences his same tribulations but bears it with a patience, a steadiness, and a love that is unequaled by mankind.