Tuesday in the Fourth Week of Lent: Ezekiel 47:1-9, 12, John 5:1-16.

Water figures strongly in today’s readings. Water is the great bringer of spiritual purification and cleanliness. God’s law prescribed that Jews must ritually purify themselves in water before partaking in everything from meals to sacrifice before the Lord. Water is also the substance of physical life, sustaining humans and all of creation. We reflected at length on the connection between the life-giving and spiritual-purifying aspects of water as presented to us in the story of Jesus at Jacob’s well with the Samaritan woman (see If You Knew the Gift!). Today, we see how water figures in prophecy about the Kingdom of God, specifically in the person of Jesus Christ.

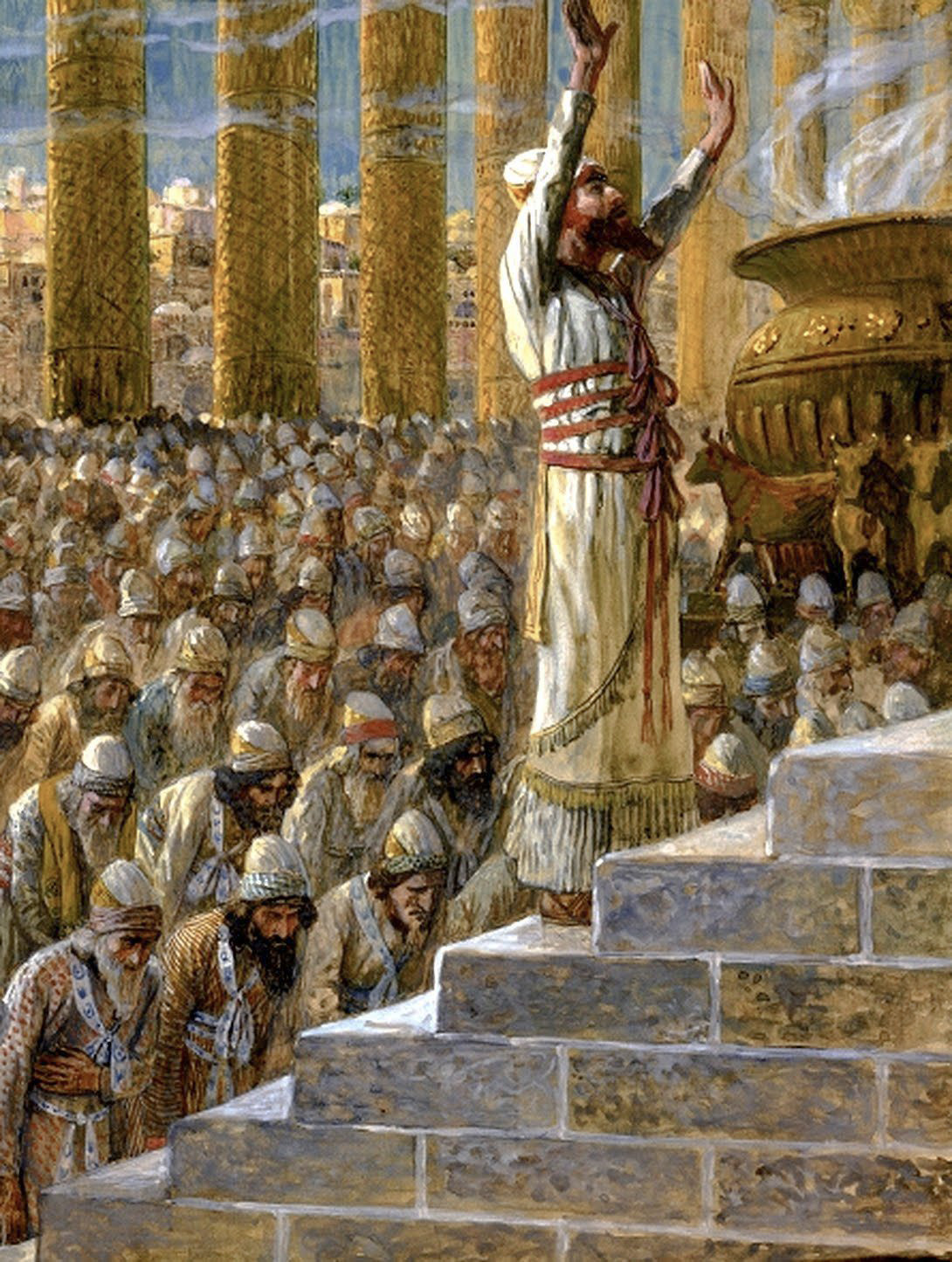

Ezekiel, like Daniel, writes during the Babylonian Captivity around the years 596-574 BC. He is given prophetic visions from the Lord about both the destruction of Jerusalem and the rebuilding of the temple. Remember that the temple in Jerusalem was the heart of the Jewish faith, where the presence of God dwells. It had supreme importance for them, and the destruction of the temple along with all of Jerusalem was a catastrophic event. Thus, when we hear of a rebuilt temple, we must understand that this is a restored connection with the presence of God.

Today’s reading is part of his vision of the restored temple; an angel shows him “water flowing out from beneath the threshold of the temple toward the east,” which is the direction that the temple faces. The angel takes him away from the temple and the water builds and deepens, first into a stream and then into a mighty river. In the east, it reveals its life-giving nature, it “empties into the sea, the salt waters, which it makes fresh. Wherever the river flows, every sort of living creature that can multiply shall live.”

This type of imagery should be familiar to us. We have explored how Jesus tells the Samaritan woman that he provides “life-giving water.” It is the endless river of life flowing from the Trinity, the “self-opening of our Thrice-Holy God,” as Jean Corbon, OP puts it. The river in Ezekiel’s vision, therefore, we can understand as the same river of life that St. John will see in the heavenly Jerusalem in the Book of Revelation. This is the eschatological vision of the river: the life abounding in the river is everlasting life.

In this eschatological vein, let’s examine the importance of the direction of the east that Ezekiel takes great pains to emphasize. One of our Church Fathers, Origen, writes of why the direction of the east is important to us: “Atonement comes to you from the east. From the east comes the one whose name is Dayspring, he who is mediator between God and men. You are invited then to look always to the east: it is there that the sun of righteousness rises for you, it is there that the light is always being born for you. You are never to walk in darkness; the great and final day is not to enfold you in darkness” (Hom. 9, 5. 10: PG 12, 515. 523.). For centuries, this is why Catholic churches have been built with the altar facing the east. We worship in the direction of Christ, the “sun of righteousness” rising for us, where “light is always being born” for us.

This brings us to the physical nexus of Ezekiel’s vision. Recall that he is describing the temple. The saving nature of the river, deep and wide in the east, points to the sacred nature of the temple. Since the river starts in the temple, our experience of divinity starts in the temple. This building (like our Catholic churches) is important because it is our physical place where we encounter God. In Christ, though, the physical and the divine co-exist. This changes everything, and even while Ezekiel was a devout proponent of all kinds of traditional Jewish religious prescriptions, his mystical vision inexorably points to a new temple that is nothing the traditional Jewish faith could envision. God is presenting him with a vision of the new temple in the person of Christ.

At many points in Christ’s ministry, He tells us how He is establishing a new priesthood (with Peter and his apostles), a new sacrifice to replace all other ritual sacrifices (the Eucharist as initiated at the Last Supper), and a new direct communion with God and God’s love through Himself. Most strikingly, he not only identifies Himself with the temple, but being greater than the temple: “I tell you, something greater than the temple is here. … For the Son of Man is lord of the sabbath” (Mt 12:6, 8). He is not abolishing physical buildings for worship, but He is re-defining the symbolic and religious meaning that the Jews placed on Jerusalem’s temple. This is most evident when the temple shroud is ripped in half and the earth shakes when He dies on the Cross. Brent Pitre, PhD, explains the importance of these events: “with the tearing of the Temple veil and the earthquake—the whole universe, ‘heaven and earth,’ were symbolically being torn asunder” (Jesus, the New Temple, and the New Priesthood, p.63). Again, with Jesus being the physical union of divinity and humanity, everything changed.

Pitre’s article referenced above is a great academic deep-dive into the implications of Jesus replacing the Jewish concept of the temple in Jerusalem. He traces the depth of the temple in Jewish consciousness: “From a theological and liturgical perspective, for a first-century Jew, the Temple was at least four things: (1) the dwelling-place of God on earth; (2) a microcosm of heaven and earth; (3) the sole place of sacrificial worship; (4) the place of the sacrificial priesthood” (48). It’s worth a read if you’re interested in exploring this further, and it certainly underscores the radical nature of Christ’s message for the Jewish people.

One last item to note from Ezekiel’s vision: the fruit born by the trees growing on the banks of the river has a life beyond the river. He says, “Every month they shall bear fresh fruit, for they shall be watered by the flow from the sanctuary. Their fruit shall serve for food, and their leaves for medicine.” As we have explored in previous reflections, Jesus counsels us in discerning between good and bad prophets, “by their fruits you will know them” (Mt 7:20). The idea is that the fruit reveals the heart of the person: “every good tree bears good fruit, but the bad tree bears bad fruit” (Mt 7:15). Thus, when Ezekiel tells us that the fruit growing on the banks of the river of life “shall serve for food and their leaves for medicine,” the Word of God is telling us that those who are fed by this divine river will be transformed in goodness, in turn feeding and healing those in the world. This is the action of God’s mercy and agape as he works his will through us.

Turning to the gospel, we find the incarnate Word of God in Jerusalem for a Jewish feast day and he is by the Sheep Gate. This likely references the sheep market where people could buy sheep for sacrifice at the temple. There are also pools there, presumably used to ritually wash the animals before they were used in the temple. “In these lay a large number of ill, blind, lame, and crippled. One man was there who had been ill for thirty-eight years.” A few things are being conveyed to us. First, Jesus is drawn to the place where the outcasts go in a bid to purify themselves like the sacrificial animals. More than outcasts, in the Jewish mind they were spiritually unclean. They exhibit a certain desperation in waiting for a “stirring” of the waters by an angel whereby the first one in the water is cleaned by divine action. We might be reminded of the story of the Canaanite woman begging for Christ’s mercy and healing: “Even the dogs eat the crumbs that fall from their master’s table” (Mt 15:27).

But here there is even deeper symbolism because this is the temple, these are waters meant to be used for purification in order to give sacrifices to the Lord. When Jesus asks the paralytic “Do you want to be well?” the man answers pitiably, “I have no one to put me into the pool.” He does not ask the Lord to heal him, for he does not recognize who He might be. He simply laments his predicament. Despite his pitiful state, the man has undiminished hope and faith, having been ill for 38 years.

Given the logic of healing stories, we might expect that Jesus will be the one to “put him into the pool,” perhaps after first asking for his faith in God. But that’s not what happens. Jesus has something deeper to say and do. He instead says, “Rise, take up your mat, and walk.” Several things happen here. First, Jesus cuts through the ritual nature of the temple, displayed in this outlying washing pool for sacrificial animals and the infirm where the first one in the pool gets healed. He establishes a new, direct connection to healing in Himself. This is underscored by his instruction to “take up your mat,” which provides a temporary dwelling place for the man in the temple. That dwelling is no longer needed. Second, he provides the divine energy personally to the man so that he can rise by himself and walk on his own. The river of life enables us to “bear fresh fruit” of our own. The man is enabled to be fully human, blossoming in the love of God. Third, Jesus performs an act of healing on the Sabbath.

The Jews, particularly the Pharisees and scribes, will use this act of “work” on the Sabbath to persecute and eventually arrest Jesus. It is a major theme of the gospels, and juxtaposes their hangups with particularities of the law while disregarding the Spirit of God among them. But have you ever wondered that Jesus might be intentionally healing on the Sabbath, not just doing his ministry as if it were any other day? Let’s return to the quote from Matthew I referenced earlier: “I tell you, something greater than the temple is here. … For the Son of Man is lord of the sabbath” (Mt 12:6, 8). Christ is establishing in Himself, here at the temple in today’s reading, what he says in that passage from Matthew. Here, in the temple, he does the “work” of replacing the temple through his own saving person and mission. As the Lord of the Sabbath, united with God to whom the sacrifice is being offered, he releases humanity from our ritual debt of sin offerings and atonement.

In yesterday’s Office of Readings, we read the account from Leviticus on the complicated ritual for Yom Kippur, the Day of Atonement, with all of its purifications, sacrifices, and sprinkles of blood. Notably, one lamb was to be sacrificed to God while the other was to have all of the Jews’ sins cast upon its head and released into the desert as an offering to Azazel (a fallen angel, much like Satan). In today’s readings, we encounter sheep at the Sheep Gate — literal sheep, the infirm who are the pitiful sheep lost to their people, and the Lamb of God Himself. The Lamb of God replaces all of these sacrificial sheep and he saves those lost sheep.

Yesterday’s Office of the Readings also gives us Origen’s commentary (quoted earlier). Here is another important link from Origen: “God taught the people of the old covenant how to celebrate the ritual offered to him in atonement for the sins of men. But you have come to Christ, the true high priest. Through his blood he has made God turn to you in mercy and has reconciled you with the Father. You must not think simply of ordinary blood but you must learn to recognize instead the blood of the Word. Listen to him as he tells you: This is my blood, which will be shed for you for the forgiveness of sins.“

Once again, we encounter Christ in all his fullness today, enacting his saving mission with every word and deed. We must strive to see the mystery hidden deep within each passage from the Word of God. Jesus gives us a profound understanding of the water that flows from the new temple: it is Him, it restores our humanity and enables a new communion with the divine.