Friday in the Second Week of Lent: Genesis 37:3-4, 12-13a, 17B-28a, Matthew: 21:33-43, 45-46.

Today’s readings are riches in storytelling and spiritual importance. I don’t mean to give short shrift to Joseph and his jealous brothers in Genesis, but I must explore it rather briefly to leave space to plumb the depths of the Parable of the Wicked Tenants in the gospel reading from St. Matthew.

These two stories are, of course, quite related. Joseph is a very early figure in the Bible who prefigures Jesus. He is the favored son, given visions and special graces from God the Father. He is persecuted by those closest to him and finds adoption by an alien people. Finally, he never stops loving even those who sold him into slavery and ends up saving them during a time of famine and establishing a new home for them.

What strikes me about today’s reading is what becomes of us when we allow ourselves to be consumed by jealousy and are taken over to sin. Listen to the brothers: “Here comes that master dreamer! Come on, let us kill him and throw him into one of the cisterns here; we could say that a wild beast devoured him. … just throw him into that cistern there in the desert; but do not kill him outright. … What is to be gained by killing our brother and concealing his blood? Rather, let us sell him to these Ishmaelites.” This spiral of evil conspiracy starts with the seed of jealousy, planted in their hearts by the devil. It is not something they push away with prayer and trust in God. Instead, it festers and manifests by calling him names, degrading him. This enables them to see him as something other than fully human (much less their brother). Then we hear a sequence of plots and machinations. They have already given themselves over to sin and evil, and this sequence smacks of the guilty desperately trying to find a way not to be found out. We must recognize this tortured logic because we encounter it in ourselves in many ways. Whenever we find ourselves making certain calculations and rationalizations to avoid a certain end, it is a good time to sit up and examine what exactly we are doing. Are we living in the light or are we obscuring our actions because we’re heading down a path of darkness? This is not to say that all situations are easy and straightforward — indeed, many take careful thought and weighing of moral issues — but it is a good reminder in this Lenten season of what our more quiet soul-searching can do for us in a busy modern world.

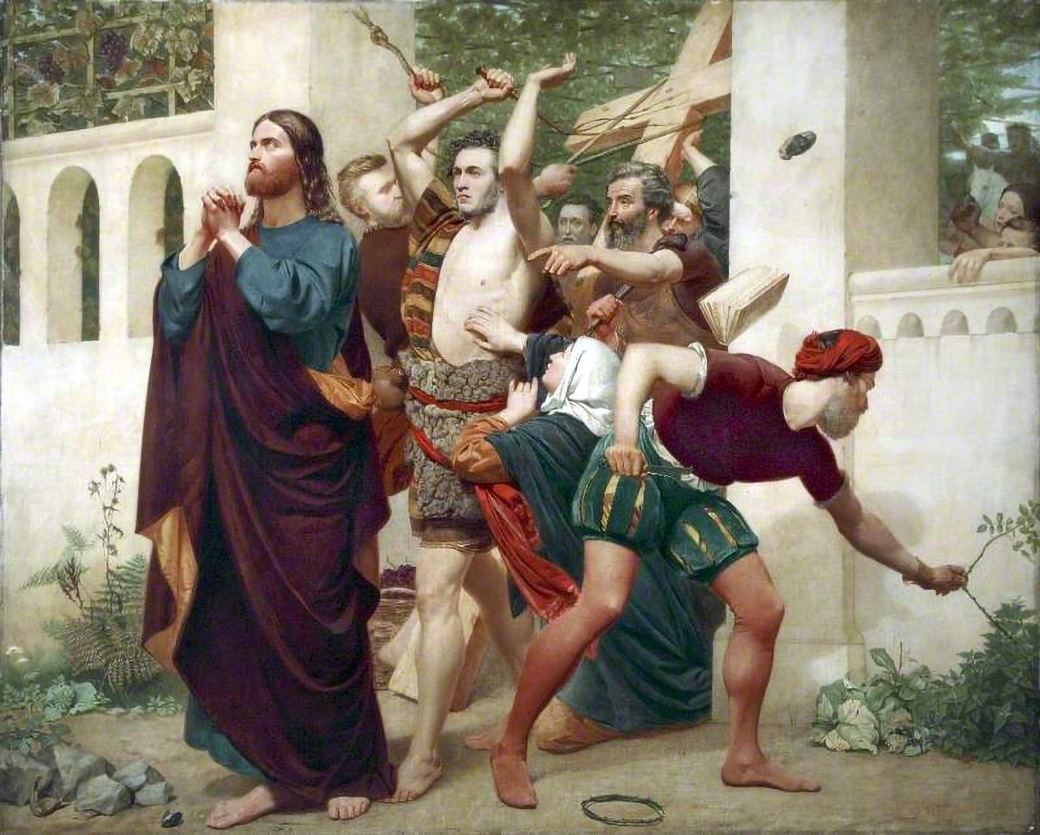

Jesus is all-too-aware of the plots and machinations of the chief priests and elders of the temple who want to arrest him. They, too, are already guilty of having sinned in their hearts and turned away from the light. For them, he presents the Parable of the Wicked Tenants.

Central to the parable is the setting: a vineyard. His listeners would immediately identify the vineyard with Israel since one of the more famous and eloquent passages in Isaiah is “The Song of the Vineyard”:

Let me sing for my beloved

my love-song concerning his vineyard:

My beloved had a vineyard

on a very fertile hill.

He dug it and cleared it of stones,

and planted it with choice vines;

he built a watchtower in the midst of it,

and hewed out a wine vat in it;

he expected it to yield grapes,

but it yielded wild grapes. …

For the vineyard of the Lord of hosts

is the house of Israel,

and the people of Judah

are his pleasant planting; (Is 5:1-2, 7a).

Isaiah’s verses question why wild grapes have grown rather than choice grapes, and Jesus answers: it is the evil in the tenants who were entrusted to care for the vineyard.

Against the important backdrop of a vineyard, Jesus weaves a parable that presents the scope of salvation history. First, we see creation: the landlord planted a vineyard, put a hedge, dug a wine press, and built a tower. Next, the election of the nation of Israel as a hope for the world: “Then he leased it to tenants and went on a journey.” Then, we see the long line of prophets who were sent to the people as well as their brutal rejection: “the tenants seized the servants and one they beat, another they killed, and a third they stoned.” Next, we see the time of Christ, when the son comes to “obtain the produce,” but he, too, is killed. Finally, we are given the question about the final judgment: “What will the owner of the vineyard do to those tenants when he comes?” Because it presents the history of God’s work of salvation in a concise allegory, this parable should be precious to us.

In his masterwork volumes on the gospel of St. Matthew, Fire of Mercy, Heart of the Word, Erasmo Leiva-Merikakis points out how central to the story (both the allegory and our reality) is the absence of the landowner. God’s physical absence is what makes the life of faith so important and what makes his return so anticipated. In Volume III, Leiva-Merikakis states, “The master’s physical absence is a kind of mystical vacuum that generates a tremendous moral crisis exposing the innermost heart of the tenants, revealing it in all its perversity” (468). Why, in fact, does God leave us to begin with? Leiva-Merikakis points out that the Hassidic answer “is that God must be absent for man’s sake, that is, if man is ever to grow fully into his divine vocation of becoming the eyes and hands and Heart of God in this word, the very dwelling place of God’s glory and truth” (468).

God’s absence presents us with the choice: either trust in Him, His wishes, and His eventual return, or choose to forget that He was ever here and act like it’s all in our hands to do what we want. Clearly, the wicked tenants in the parable, who Jesus points out are the chief priests and Pharisees, have chosen the second option.

But let’s not forget that God cares deeply about his beloved vineyard, the tenants, and the precious fruit he waits for it to bear. That’s why he sends his servants (the prophets) time and again, as well as his son. When Jesus asks the priests and elders what the landlord will do to the tenants, they rightly answer, “He will put those wretched men to a wretched death and lease his vineyard to other tenants who will give him the produce at the proper times.” But God is not focused on the retribution for the wrongdoing. Instead, Jesus replies to their answer with the following from scripture: “The stone that the builders rejected has become the cornerstone; by the Lord has this been done, and it is wonderful in our eyes.” His Good News is that God’s work and presence in the world is restored. The “stone that the builders rejected” refers to the new tenants who will better care for the vineyard. Who exactly are they?

The tenants (and the rejected cornerstone) begin with Christ. He is rejected by his people, but becomes the cornerstone of a new reality of salvation alive in the world. And it is wonderful in our eyes. This new reality of salvation happens in the presence, not the absence, of the Spirit of Christ, alive in the world after the Resurrection. This makes us the new tenants in as much as we share Christ with the world. In his high-priestly prayer at the Last Supper, Jesus affirms this aspect of the Church: “The glory that you have given me I have given them, so that they may be one, as we are one, I in them and you in me, that they may become completely one, so that the world may know that you have sent me and have loved them even as you have loved me” (Jn 17:22-23).

Leiva-Merikakis elaborates: “When people look for God in a visible form, they will see only each other. When they look for Christ, they will see only Christians. By giving us his own animating and sanctifying Spirit, Christ has entrusted us with everything that is his. No, ‘entrusted’ is not to say enough. Through his death and Resurrection, he has implanted in us a wholly new life, with all the same energies and principles of life that give thrust to his own life” (469).

If we are in part the new tenants, are we (or our deeds) not also the fruit that the landlord will find? This is the question of all of salvation history: what kind of fruit will the landlord find? God has given us the ability to tend the vineyard through Christ’s Spirit active in our lives, but our deeds and charity, indeed all that we do here on earth are our fruits. Can we wisely accept the Spirit of Christ in our lives as a landlord who is present? Or will we continue to act as the Israelites did and conform to the law externally while having no internal relationship to the truth? Each of us this Lent has the opportunity to re-dedicate ourselves to tending the vineyard with Christ and bringing forth the fruits pleasing to the Lord.

Pingback: Rejoice for the Pardon of the Prodigal