Wednesday in the Second Week of Lent: Jeremiah 18:18-20, Matthew 20:17-28.

Today’s readings display two things clearly: how clueless the chosen people can be, and (somewhat related) the inevitable persecution of those who proclaim the Word of God.

Jeremiah was a prophet 100 years after Isaiah, and the major power threatening Israel and Judah is no longer Assyria but Babylon. The unfaithfulness of the Jews, however, is a common thread, and we find them once again worshipping other gods and not being faithful to the God of Abraham. Jeremiah is a bold prophet, not afraid to proclaim the difficult words God gives him. The Word, which will become flesh in Jesus, is shown to be unstoppable, even though Jeremiah gets beaten, put in stocks, and later thrown in a pit to die. Jesus, too, will pay the price for bringing the Truth to humanity.

The section we hear today happens in the midst of a classic metaphor where we are the clay and the Lord is the potter. Given my upbringing with the dulcet folk tunes played in our church, I always associated this verse with a gentle potter shaping us in love. And certainly this would be the case in the Book of Jeremiah if the Jews had obeyed God’s commandments, but that’s not the case. It’s much more neutral. God’s message is that, as the potter, He can do as he pleases with the malleable clay. He can mold a nice vessel with the nation of Israel or utterly destroy what he’s building and start over. He ends his analogy by commanding Jeremiah to tell the people, “Look, I am a potter shaping evil against you and devising a plan against you. Turn now, all of you from your evil way, and amend your ways and your doings” (Jer 18:11b).

(Just imagine the tune “Abba, Father” with dark and haunting chords.)

The Jews respond to Jeremiah’s message: “But they say, ‘It is no use! We will follow our own plans, and each of us will act according to the stubbornness of our evil will'” (Jer 18:12). So, God says he will make their land a horror, “a thing to be hissed at forever.” Then we get to today’s passage.

I’m going into this detail because, on one hand, Jeremiah’s words in the selected text today seem very much like a mirror of Christ’s trials to come. The people say, “let us destroy him by his own tongue; let us carefully note his every word.” This sounds like the plots of the Pharisees and scribes in trapping Jesus in his own teachings. Even more in the final verses: “Must good be repaid with evil that they should dig a pit to take my life? Remember that I stood before you to speak in their behalf, to turn away your wrath from them.” We could imagine Christ uttering similar words in the Garden of Gethsemane. In today’s passage from Jeremiah, we see the Word of God enduring similar treatment that He will endure in Christ 600 years later.

But the parallels end as we look at the full context of Jeremiah. In fact, there is a stark difference in the way Jesus accepts his cross and offers his suffering and Passion to the Father “as a ransom for many” (more on that below), and the way Jeremiah reacts with righteous indignation. Here is the frightening verse immediately following the ones from today’s reading: “Therefore give their children over to famine; hurl them out to the power of the sword, let their wives become childless and widowed. May their men meet death by pestilence, their youths be slain by the sword in battle” (Jer 18:21). Oy! Jeremiah, what are you wishing upon your fellow people?? Sounds like straight-up revenge talk to me. Yes, they may deserve it, but where’s the begging for mercy such as Abraham did on behalf of Sodom or Moses did time and again for the unfaithful Israelites in the desert? (It’s worth noting that whatever his personal bitterness, Jeremiah continued to follow God’s instructions to the letter. When he takes an earthenware jug and breaks it in front of the people as a symbol of how they will be broken by the potter, this is the beginning of a string of doomsday-ish prophecies leading up to the Babylonian Captivity. But he also spreads prophecies of hope after that for Israel and Judah to be restored.)

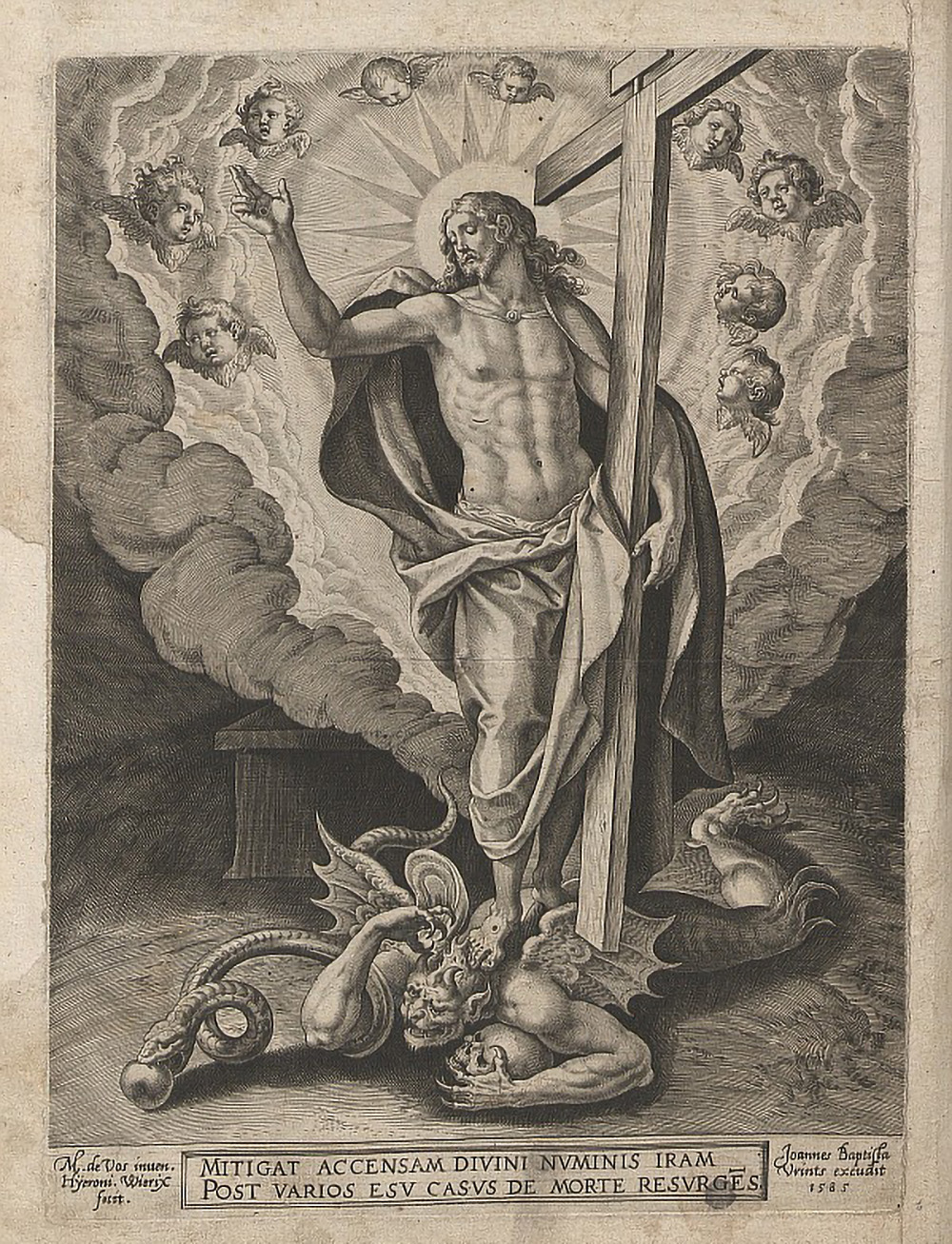

Now let’s turn to the gospel reading from St. Matthew. Jesus tells his apostles as clear as day what awaits when they get to Jerusalem: “and they will condemn him to death, and hand him over to the Gentiles to be mocked and scourged and crucified, and he will be raised on the third day” (speaking of the “Son of Man,” who He is). But they remain clueless. So much so that the next thing Matthew reports is that the mother of James and John, Zebedee’s wife, comes before Jesus to ask that her sons “sit, one at your right and the other at your left, in your kingdom.” There is good evidence here to assume that she, like all of them, still thinks there will be an earthly kingdom, where the Romans will be driven out and the descendent of David (Jesus) will sit on the kingly throne of a restored Jewish nation. As a funny aside, our Fr. Erik shared his nickname for James and John in morning Mass today: “Mama’s boys,” due to today’s reading.

Jesus asks if they can drink of the chalice that he will drink and they blithely respond, “We can,” which I read as “Sure!” Maybe they were thinking of a jewel-encrusted chalice of victory, but we in retrospect know better. Jesus patiently and knowingly affirms that they will (James is the first martyred apostle) but deflects the question at hand by saying it is the Father’s choice in terms of who will be at his right and his left when he enters the kingdom. We know that it will be the two thieves crucified with Christ, drinking of that chalice of suffering. There’s a lesson in “watch out what you ask for.”

The ensuing “indignation” of the other ten apostles provides a good teaching opportunity for Jesus. He reiterates a theme we reflected upon yesterday: “whoever wishes to be first among you shall be your slave,” that is, humility must reign, not lording authority over others (see Led by the Master for a deeper discussion of humility). As their heads are filled with visions of an earthly empire like King Solomon, King David, and others in their history, this message was probably received as a bit of simple peacemaking, an Apostles’ Code of Good Conduct.

But it’s so much more. It’s the essence of the Trinity and the mystery by which our salvation is gained. So Jesus pushes deeper: “Just so, the Son of Man did not come to be served but to serve and to give his life as a ransom for many.” He wants them to understand that humility and service are the core of His mission. These are more than behavioral codes — they are ways to embody the selfless love that endlessly flows between the persons of the Trinity, and He will be giving them an ultimate example of humility and service in just a week’s time.

The fulcrum here is the word “ransom.” We use the word ransom in reference to extortion, when someone is held against their will, and the ransom is the payment to free them. The Greek word used by Matthew, λύτρον, means ransom, but more specifically a payment to free slaves, which is different than extortion payments. For millennia, theologians have formulated various Ransom theories of atonement, going down the rabbit hole, asking “to whom is the ransom payment made? The devil? Death? Back to God?” But I think the important point Jesus wants to make is that his selfless sacrifice is a severing of an enslavement, a change of the ontological status of humanity; in other words, we were a people fundamentally enslaved in sin and death, but his sacrifice for us makes us a people freed from that enslavement and welcomed into the Kingdom of everlasting life.

In fact, we find the Word of God speaking 750-some years earlier through the mouth of the Hosea, prophesying this ransom. The NRSV Bible translates it as: “Shall I ransom them from the power of Sheol? Shall I redeem them from Death?” The Hebrew word אֶפְדֵּ֔ם translated as “ransom” is, like the Greek, not tinged with our references to extortion. It means to sever, i.e., ransom; or more generally to release or preserve. And here in Hosea we see the Word of God making it clear that the enslavement is to death.

Back to Jesus’s words “to serve and to give his life as a ransom for many.” Jesus is the ransom payment that releases us from the bondage of death and sin, but not a payment of inert money. His ransom is an active, divine energy inherent in service and humility. What a complex thought. Something that we think of as a static thing, a payment, can be an active process to be lived and replicated. Just so, our God, who we might relegate to being a static “old guy in the sky” is an active energy in the world, then and now. This is getting abstract, but stay with me because the important pivot here is that Christ’s ransom is not just a one-time thing. It’s a once and forever thing.

Christ’s ransom converts the potential energy of hope and salvation into a reality, a kinetic energy of living with God. Yes, we get to live with God in the Kingdom here and now, a real communion. The liturgy is our ongoing communion, freed from enslavement. We not only commemorate but re-celebrate Christ’s sacrifice during the liturgy so that the sacraments re-instill the divine energy in us as we fall away into sin and require constant re-dedication to God. There is much more to say about how important it is that Eucharist is the actual body and blood of Christ because his ransom is essentially about the flesh of the world, death, and rising in spirit … but let’s leave that for another day.

May we not be like the Mama Zebedee and the Jews of Jeremiah’s time, focused on the present and clueless to the truth revealed by the Word of God. And may we forever thank God for sending His Son as a ransom for us. So much better than human prophets like Jeremiah who got fed up and called down bitter revenge for our sins!